"It's not a very big firm, Chickie, not a very big firm at all. There's myself and my partner, and we each earn somewhere between ten and fifteen thousand dollars a year, I want you to know that."

"Sidney, I never asked you what—"

"I know, and I appreciate it, but I want you to understand the full picture. I'm not what you would call a very successful lawyer."

"Sidney, you're a very good lawyer."

"Well, I hope so, but I'm not a very successful one. There are lawyers in this city who can count on a hundred thousand dollars even in a bad year. I'm not one of them, Chickie."

"Why are you telling me this?"

"Because I want you to know."

She looked at him curiously, and then frowned. "You're not going to cry or anything, are you, Sidney?"

"No."

"Because I really haven't got time for that"

"No, I'm not going to cry," he said.

"Good. What is it then?"

"If I win this case, Chickie, I will be a very big lawyer."

"Will you?"

"We're suing for an accounting of profits, Chickie. It's our estimate that the movie earned in the vicinity of ten million dollars. We can't tell for certain because API isn't required to produce its books unless we win, or unless they're necessary to show we are entitled to an accounting. But ten million dollars is our guess."

"Sidney. " she started, and frowned, and glanced at her watch.

"I'll tell you the truth, neither Carl nor I wanted to take it on at first, my partner. We weren't sure there was a case, we knew very little about plagiarism. But you'd be surprised, Chickie, you'd really be surprised at how many plagiarism cases have been won on evidence that seems silly at first, similarities that seem ridiculous. The ones Constantine pointed out seemed just that way to us in the beginning, until we had a chance to examine them in the light of other cases. There was copying, Chickie, I sincerely believe that now. Driscoll was clever, yes, he altered, yes, disguised, yes, but he copied. I believe that, Chickie, I'd better believe it — the case has already cost the firm close to ten thousand dollars, not to mention time, but it'll be worth it if we win." Sidney paused. "The fee we agreed to is forty per cent of whatever we recover. Do you understand me, Chickie?"

"I think so," she said. She was still frowning, but she was listening intently now.

"Forty per cent of ten million dollars is four millon dollars, Chickie. If we win this case, my partner will get two million dollars and I will get two million dollars. I will be a very r-r-rich man, Chickie, and v-v-very well-known." Sidney paused. "I will be a successful lawyer, Chickie."

"You're a successful lawyer now," she said.

"Not like J-J-Jonah Willow."

"You're every bit as smart as Willow," she said. "Don't stammer."

"Yes, but not as successful." He paused. "Maybe not as s-s-smart, either, I don't know."

"You're just as smart, Sidney."

"Maybe," he said. He paused again. "Chickie, as you know, I have a widower father to support, he has a garden apartment in Queens, he's a very old man, and no trouble at all. I pay the rent each month, and I give him money to live on, that's about the extent of it."

"Yes, Sidney."

"Chickie, I've been wanting to ask you this for a long time now, but I never felt I had the right. I'm forty-eight years old, going on forty-nine, and I know you're only twenty-seven and, to be quite truthful, I've never been able to understand what you see in me."

"Let me worry about that," she said, and began stroking the back of his neck.

"B-b-but, I feel certain I'm going to win this case and that would ch-change things considerably. That's why I f-f-feel I now have the right."

"What right, Sidney?"

"I guess you know I 1-1-love you, Chickie. I suppose that's been made abundantly apparent to you over the past several months. I am very much in love with you, Chickie, and I would consider it an honor if you-were to accept my p-p-proposal of matrimony."

Chickie was silent.

"Will you marry me, Chickie?"

"This is pretty unexpected," she said. Her voice was very low. He could barely hear her.

"I figured it would come as a surprise to you."

"I'll have to think about it, Sidney. This isn't something a girl can rush into."

"I realize that."

"I'll have to think about it."

"I'll be a very rich man when I win this c-c-case," Sidney said.

"You dear man, do you think that matters to me?" Chickie asked.

He lay full length on the bed opposite the window, his hands behind his head, staring up at the ceiling. He had been lying that way for close to an hour now, ever since their return to the hotel room. He had not closed his eyes in all that time, nor could Ebie fool herself into believing he was actually resting. There was a tautness in his very posture, an unseen nervous vibration that she could feel across the length of the room. His silence was magnified by the rush-hour babble from below. In the echoing midst of headlong life, he lay as still as a dead man and stared sightlessly at the ceiling.

"Are you all right?" she asked.

"I'm fine," he said.

"Dris?" '

"Yes?"

"I'm afraid."

"Don't be afraid, Edna Belle."

"Can't we talk?" she asked.

"What would you like to talk about?"

"Can't… can't you reassure me? Can't you tell me we're not going to lose?"

"I'm not sure of that, Edna Belle."

"Please don't call me Edna Belle."

"That's your name isn't it?"

"My name's been Ebie for the past God knows how long, please don't call me Edna Belle. I hate the name Edna Belle. You know I hate the name."

"Ebie is an affectation," he said.

"It's not an affectation, it's my name . It's an important part of me."

"Yes, I'm sure it is."

"Yes, it is."

"I said yes."

"Then please don't call me Edna Belle."

"I won't."

"And if you feel like getting angry, please…"

"I'm not getting angry."

"… don't get angry with me. You have no reason to get angry with me."

"That's true. No reason at all."

"Get angry with Constantine, if you want to get angry. Or his lawyer. They're the ones who are trying to ruin us."

"If you ask me," he said, " you're the one who's getting angry, not me."

"Because you're not giving me the assurance I need."

"False assurance is a beggar's—"

"Don't try to get literary," Ebie said.

"Was I getting literary?"

"You were trying to, there's a difference. I can't stand it when you try to sound like a goddamn novelist."

"Have no fear. I am not a goddamn novelist."

"What are you then?"

"A Vermont farmer."

"You were a novelist before you were a farmer."

"I have never been a novelist," he said.

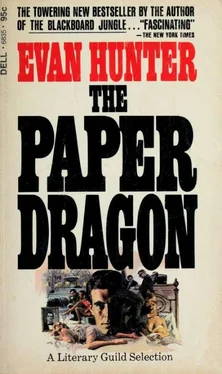

"No? What do you call The Paper Dragon ?"

"Luck," he said, and closed his eyes.

The room was silent. From the street below, she could hear someone shouting directions to a truck driver at the Times depot. In the distance, Sardi's neon sign stained the dusk a luminous green, and the surrounding gray and shadowy buildings began to show lights in isolated window slits. She stared at him without speaking, and then pressed her face to the glass and watched the truck as it backed into the depot. How simple it is, she thought. How simple they make everything. When she turned to him again, her voice was very low. "They can take it all away from us," she said. "We can lose everything, Dris."

"We lost everything a long time ago," he answered. His eyes were sill closed.

"No."

"Ebie. We lost everything."

"Thank you," she said, and sighed. "That's the reassurance I wanted, thank you." She glanced through the window. "That's the encouraging word I wanted, all right," she said, and pressed her forehead to the glass.

Читать дальше