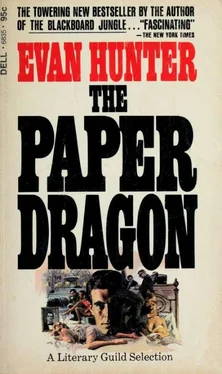

Evan Hunter - The Paper Dragon

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Evan Hunter - The Paper Dragon» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1967, ISBN: 1967, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: roman, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Paper Dragon

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1967

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0094530102

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Paper Dragon: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Paper Dragon»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

But as each day passes, the suspense mounts in an emotional crescendo that engulfs them all — and suddenly one man's verdict becomes the most important decision in their lives…

The Paper Dragon — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Paper Dragon», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The anger exploded suddenly, the way it always did, they were sitting in the kitchen upstairs, the second floor over the store, and his mother began berating Sidney's father for what Sidney thought had been his really courageous behavior and suddenly she went off, click, it was always like that, click, as though a switch were thrown somewhere inside her head, short-circuiting all the machinery, click, and the anger exploded. She got very red in the face, she looked Irish when she did, and her green eyes got darker, and she would bunch her slender hands into tight compact fists and stalk the kitchen, back and forth, the torrent of words spilling from her mouth in steady fury, not even making sense sometimes, repeating over and over again events long past, building a paranoid case, well, no not paranoid, building a case against the world, reliving each injustice she had ever suffered at the hands of the goyim, at the hands of childhood friends, at the hands of his father's family, at the hands of her ungrateful whelp of a son, nothing whatever to do with the drunken wino (or whoever or whatever it happened to be), the supposed original cause of her anger. "No justice," she would scream, "there's no justice," and the flow of words would continue as she paced the kitchen before the old washtub, and Sidney's father would go to her and try to console her, "Come, Sarah, come, darling," and she would throw off his imploring hands while Sidney sat at the oilcloth-covered table in terror, thinking his mother was crazy or worse, well not crazy, "She's excited," his father would say, "she's just excited."

Those were not happy times. The war had ended long ago, but the Depression was on its way, and there would come a day when even Bowery bums no longer cared whether or not they were wearing almost-new shoes, or any shoes for that matter, when the best defense against a nation sliding steadily downhill was indeed a bottle of hair tonic in a dim hallway stinking of piss. He came to look upon those Bowery ghosts as a symbol of what America had become, and he dreaded growing up, becoming a man in a world where there were no jobs, and no justice, especially for Jews. He was very conscious of his Jewishness, not because anyone called him Jewboy — hardly anyone ever did since he hung around mostly with other Jewish kids, and since all of his relatives were Jews, and every function he attended was either a Jewish wedding or a bar mitzvah or a funeral, well, yes, there was that one incident, but even that was not so terribly bad, his mother's anger afterwards had been worse than the actual attack — he was conscious of his Jewishness mostly in a religious way, strange for a young boy, almost a holy way, everybody in the family said that Sidney would grow up to be a rabbi; In fact, his Uncle Heshie from Red Bank used to jokingly call him Red Shiloach, and this always pleased him enormously because he thought of the town rabbi, the old rabbi in the Polish town from which his mother and father had come, as a very learned man who dispensed justice, who read from the Holy Book and dispensed justice to Jews, the one thing that had somehow been denied his mother only because she was Jewish. He sometimes visualized himself in the role of the Talmudic scholar, searching for the holy word that would put an end to his mother's anger, "Look, Mama," he would say, "it is written here thus and so, so do not be angry." And all the while, he feared the anger was buried deep within himself as well. He had seen murder in his mother's eyes, he had heard hatred in her voice, had the seed really fallen too terribly far from the tree? Was it not possible that he too could explode, click, the switch would be thrown in his head, click, and being a man he would kill someone? Later, when it happened with the Irish kids, when they surrounded him that day and pulled down his pants and beat him with Hallowe'en sticks and he did not fight back, he wondered whether he was really a person in whom there lay this secret terrible wrath, or whether he was simply a coward. He only knew for certain there had been no justice for him that day, that he had done nothing to warrant such terrible punishment, such embarrassment, the girls standing around and looking at his naked smarting behind, and later crossing their fingers as he walked home, "Shame, shame, we saw Sidney's tushe , shame, shame," chanting it all the way home like a litany, there was no justice that day, but neither had they called him Jewboy. Maybe they just wanted to take down my pants, Sidney reasoned later, who the hell knows?

The wrath exploded that night, he was certain it would, and it did. He did not at the time connect any of his mother's explosions with sex — if you had asked anyone on the Lower East Side who Sigmund Freud was, they'd have recalled the man who peddled used china from a pushcart on Hester Street and whose name was Siggie Freid — but in later years it seemed to him that the justice she so avidly sought was somehow connected with events that invariably concerned sex, and he began wondering what could possibly have happened to his mother back in Europe. But no, he never really consciously thought that, no one ever consciously thinks that about his own mother, it only came to him on the gray folds of semirecognition — the wino had said, "You've got some tits there, lady," the Irish boys had taken down Sidney's pants, the sewing machine salesman had asked if he could step into the parlor for a moment, the argument with Hannah Berkowitz had involved the use of too much rouge, the girl his mother found him with on the roof was Adele Rosenberg who was sixteen years old and wore no bloomers in the summer, but everybody knew that, not only Sidney, and besides they weren't even doing anything. All these events returned to him grayly, darkly, as though on a swelling ocean crest that dissipated and dissolved before it quite reached the shore, leaving behind only vanishing bubbles of foam absorbed by the sand. The black and towering fact remained his mother's anger, which was to him inexplicable at the time. It was simply there . Uncontrollable, raging, murderous. He would dream of bureau drawers full of women's hair, brown and tangled. He would dream of hags sitting next to him in movie theaters, opening their mouths to expose rotten teeth and foul breath. He would dream of running through castles where dead bodies were stacked end upon end, decomposing as he raced through them, filling his nostrils with suffocating dust.

He feared his mother, and he pitied his mother, and he despised his mother. And he loved her as well.

Because of her, he never lied about being a Jew. A lot of the kids in the neighborhood and on the block were lying in order to get jobs, this was 1934, 1935, the NRA had already come in, the blue eagles clutching lightning were showing in all the shop windows all over the city, things were a little better, but it was still difficult to get a job, especially a part-time job, and especially if you were a Jew. He never lied about being a Jew, and he never told himself that the reason he didn't get the job was because he was Jewish. He blamed his inability to find work on a lot of things — his looks, his height, the stammer he had somehow developed and which always seemed to crop up when he was being interviewed for a position, the somewhat high whininess of his adolescent voice, all of these things — but never his Jewishness. His Jewishness was something separate and apart, something of which he could be uncommonly proud, the old rabbi quietly studying the Holy Book in the sunset of his mother's town, the townspeople standing apart and waiting for him to dispense justice.

He was able to enter Harvard only because Uncle Heshie from Red Bank died and left his favorite nephew a small sum of money, sizable enough in those days, certainly enough to pay for Sidney's undergraduate education. He left for Boston in the fall of 1936. He was eighteen years old, and five feet eight inches tall (he assumed he had grown to his full height, and he was correct). He had black hair parted close to the middle and combed into a flamboyant pompadour that scarcely compensated for the cowlick at the back of his head. He came directly from Townsend Harris High School, where his grades had averaged 91 per cent, and from which he had graduated with honors.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Paper Dragon»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Paper Dragon» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Paper Dragon» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.