Evan Hunter - The Paper Dragon

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Evan Hunter - The Paper Dragon» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1967, ISBN: 1967, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: roman, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

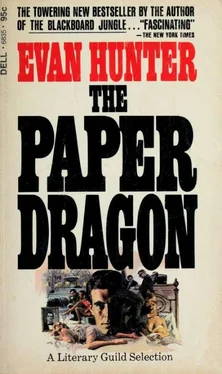

- Название:The Paper Dragon

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1967

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0094530102

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Paper Dragon: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Paper Dragon»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

But as each day passes, the suspense mounts in an emotional crescendo that engulfs them all — and suddenly one man's verdict becomes the most important decision in their lives…

The Paper Dragon — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Paper Dragon», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"Thank you."

The room was silent. It could have been a shuttered room in Panama, there was that kind of afternoon hush to it, the waning light against a drawn shade, the silk-tasseled lower edge, a contained lushness, the green plush chair with the gray cat purring on its arm, the moss green of the velvet curtains and the burnt sienna walls, the scent of snuffed-out candles and perfume.

He had felt in Panama, a centuries-old decadence that clung to every archway and twisted street, a miasma of evil, a certain knowledge that anything ever devised by humans had been done in this city, and he had been excited by it. Now, watching Chickie as she moved barefooted over the rug, the drink in one hand, he felt the beginning of that same kind of excitement, a welcome loss of control that he experienced whenever he was near her, a heady confusion that threatened to submerge him.

She handed him the drink. "What is it?" she asked.

"I had to ring four times," he said.

"What?"

"Downstairs."

"Is that what's bothering you?"

"Yes," he said, and accepted the drink.

"I'm sorry, Sidney, but you'll remember—"

"It's all right."

"You'll remember that I advised you not to come in the first place. I have to leave in a very few minutes…"

"Where are you going?"

"To the agency. I told you that on the phone, Sidney, and I told you I'd be very rushed."

"Why are you going to the agency?"

"I have work to do."

"I thought…"

"I have work to do, Sidney."

"All right, I'll pick you up later for dinner," he said.

"No, I can't have dinner with you tonight."

"Why not?"

"I'm having dinner with Ruth. We have a trip to work out. I told you all about it."

"No, you didn't."

"A very important trip that may materialize," she said, nodding.

"That may materialize?" he said. "I don't understand."

"Ruth and I have to work out this trip together," she explained very slowly, "that may be materializing."

"A trip to where?"

"Europe."

"For whom?"

"For a client, of course."

"But what do you mean it may be materializing?"

"Well, it isn't certain yet."

"When will it be certain?"

"Very soon, I would imagine. Your hair sticks up in the back, did you know that?"

"Yes. Can't Ruth handle it alone? There's something I wanted to—"

"No, she can't. Do you want a refill, Sidney?"

"No. Why can't she?"

"Because it would be a very long trip, Sidney. If it materializes. It would be for the entire winter, you see."

"I see."

"Until the fifteenth of June."

"I see."

"Which is why it's so terribly complicated. Are you sure you don't want a refill?"

"No, thanks. Maybe I can see you later then. There's something—"

"I'll be busy all night."

He stared at her for a moment, and then said, "Chickie, are you lying to me?"

"What?"

"Are you lying?"

"About what, for God's sake?"

"About this trip, about tonight, about…"

"Sidney, I'm a very bad liar. I wouldn't even attempt lying to you."

"I think you're lying to me right this minute," he said.

"Now stop it, Sidney," she warned. "You may have had a difficult day, but let's not start hurling silly accusations around, shall we not?"

"I'm sorry," he said. "I h-h-have had a d-d-difficult day, I'm sorry."

"That's all right, Sidney, and don't start stammering."

"I'm sorry."

"What you need is another drink," she said, and took his glass. "And then I've got to get dressed." She put two ice cubes into his glass and poured more bourbon over them. She handed the glass to Sidney and then said, "Shall I take Shah out of the room? Would you like me to do that?"

"Yes, I'd appreciate it."

"I will then. Come, Shah," she said, "come, pussycat. Sidney doesn't like you because of the Indian, isn't that true, Sidney? Come, Shah, sweetie."

She lifted the cat into her arms, cradling him against her breasts. "Drink," she said to Sidney, and then suddenly stopped alongside his chair. "Drink," she repeated in a whisper. A strange little smile twisted her mouth. She stared at him another moment, smiling, and then turned her back to him abruptly and went down the hall to her bedroom.

He sat alone in the darkening room, sipping his drink.

He supposed he would ask her when she returned, though he would have much preferred doing it over dinner. He did not relish the thought of postponing it again, however. He had been on the verge of asking her for the past week, and each time he had lost his courage, or become angry with her, and each time he had postponed it. He had the feeling he could put it off indefinitely if he allowed himself to, and he did not want that to happen. No, he would ask her when she returned, even though he was still a little angry with her.

He had to watch the anger, that was the important thing. Oh yes, there were other things as well — he talked with his hands a lot, he had got that from his father; and the stammering, of course, but that was only when he go excited; and his inability to extricate himself sometimes from a very complicated sentence, three years of Latin at Harvard, a lot of good it had done him. But the anger was the most important thing, that was the thing he had to control most of all because he knew that if he ever really let loose the way his mother… well.

Well, she was dead, poor soul, nor had it been very pleasant the way she went, lingering, lingering, he had gone to that hospital room every day of the week for six months, at a time when he had just begun the partnership with Carl and really should have been devoting all of his energies to building the practice. Well, what are you supposed to do when your mother is dying of cancer, not visit her? leave her to the vultures? God forbid. And the anger, her immense and enormous anger persisting to the very end, the imperious gestures to the special nurses day and night, oh the drain on his father, the shouted epithets, thank God most of them were in Yiddish and the nurses didn't understand them, except that one Miss Leventhal who said to him in all seriousness and with an injured look on her very Jewish face, "Your mother is a nasty old lady, Mr. Brackman" — with the poor woman ready to die any minute, ahhh.

The anger.

He had never understood the anger. He only knew that it terrified him whenever it exploded, and he suspected it terrified his father as well, who always seemed equally as helpless to cope with it. His mother had been a tall slender woman with a straight back and wide shoulders, dark green eyes, masses of brown hair piled onto the top of her head, a pretty woman he supposed in retrospect, though he had never considered her such as a child. They lived on East Houston Street, and his father sold shoes for a living, shoes that were either factory seconds or returns to retail stores. He did a lot of business with Bowery bums when they were sober enough to worry about winter coming and bare feet instead of their next drink or smoke. He had always admired the way his father handled the bums, with a sort of gentleness that did not deny their humanity, the one and only thing left to them. Except once when a drunken wino came into the store and insulted Sidney's mother, and his father took the man out onto the sidewalk and punched him twice in the face, very quickly, sock, sock, and the man fell down bleeding from his nose, Sidney remembered how strong his father had been that day. The wino came back with a breadknife later, God knows where he had got it, probably from the soup kitchen near Delancey, and his father met him in the doorway of the store, holding a length of lead pipe in his right hand and saying, "All right, so come on, brave one, use your knife." His mother called the police, and it all ended pretty routinely, except for his mother's later anger.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Paper Dragon»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Paper Dragon» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Paper Dragon» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.