Evan Hunter - The Paper Dragon

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Evan Hunter - The Paper Dragon» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1967, ISBN: 1967, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: roman, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

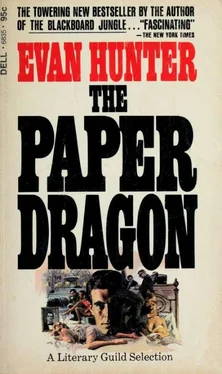

- Название:The Paper Dragon

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1967

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0094530102

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Paper Dragon: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Paper Dragon»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

But as each day passes, the suspense mounts in an emotional crescendo that engulfs them all — and suddenly one man's verdict becomes the most important decision in their lives…

The Paper Dragon — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Paper Dragon», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Besides, she was very much interested in art by this time, and was being encouraged to undertake all sorts of school art projects by Miss Benson, who was her teacher. It was Miss Benson who helped her to overcome her fear of working in pen and ink, which she had always had trouble with before, being left-handed and smearing the ink every time her hand moved across the page. Miss Benson also taught her there was a freedom to art, that once you knew what you were about, why then you were entitled to this freedom, but that first you had to earn the right to it by learning what you were about. That until you knew how to draw something in its right proportions, why then you had to draw it correctly and properly each and every time, and then, only then could you afford to go off and make an arm longer or a leg shorter or give a face three eyes or whatever. Well, she had Picasso in mind, you see, or someone like that, though Edna Belle never thought of herself as having that kind of talent, still Miss Benson was terribly encouraging.

There was no question that most of the two hundred students who attended the high school liked to hear Miss Benson's stories about Rembrandt (Charles Laughton) and Gauguin (George Sanders). Miss Benson made these men come to life somehow, as though she were adding personal information even Hollywood had missed. Besides, for students like George Benjamin anything was better than having to draw. True, it got to be something of a drag when Miss Benson went on and on about sculpture in Mesopotamia during the fourth and third millennia before the Christian era (like, man, who gave a damn?) or when she showed slides of all those broken Greek statues, but for the most part, the kids thought she was less painful than many of the biddies around. None of them, however, thought quite as highly of her as did Edna Belle.

She was, Clotilde Benson, a fluttery old woman who indeed spoke of Van Gogh as if she had personally been the recipient of his severed ear, an uncompromising, old-fashioned instructor who insisted on certain artistic verities and some artistic conceits, an unkempt and sometimes slovenly person who habitually wore a loose paint-smeared smock and who stuck colored pencils haphazardly into her gray and frizzled hair, a vain and foolish woman whose students laughed behind her back each time she sneaked a look at herself in the reflecting windows of the supply cabinet, an inadequately trained art teacher working in a scholastically poor high school in a town that had gone dead a hundred years ago. It was rumored, too, and this only by Cissie Butterfoster who was given to lurid sexual fantasies, that Clotilde Benson had once conducted a scandalous love affair with a nigger lawyer in Atlanta. The romance had supposedly begun when she was twenty years old and going to art school there, and it had ended when six righteous Georgians rode the attorney off the highway one night and proceeded to educate him (they were all carrying knives) as to why it was highly improper for a colored man to pluck a Southern flower, you dig, boy? They then casually dropped in on Clotilde that same night at about three a.m., and while she stood shivering in a flannel robe over girlish cotton pajamas with delicate primrose pattern, told her she had better get the hell out of Atlanta before somebody cut her similar to how they had cut that nigger lawyer, or hadn't she heard about that yet? Clotilde admitted as to how she hadn't heard a word, trembling in the night and holding her flannel robe closed at the neck over her primrose-patterned girlish cotton pajamas. The six gentlemen all took off their hats and murmured good night to her in the dark, and she heard one of them laugh softly as they went out of the driveway and into the waiting car and — according to Cissie — that very same morning Miss Benson caught an early train out of Atlanta and back home, apparently having decided she'd had enough of all this Gauguin-type reveling, and convinced that such living only led to shame and degradation. That was Cissie's story, and it sounded good, and there were plenty of kids who were willing to believe it, although none of them ever had the courage to repeat it. The only one who neither repeated it nor believed it was Edna Belle. Oh yes, she believed that maybe Miss Benson might have possibly been in love with a nigger (although the idea was pretty repulsive) but she would never in a million years believe Miss Benson had turned tail and run like that, even if the man had've been a nigger like Cissie said, though Cissie was a big liar, anyway.

One afternoon — autumn came late to Edna Belle's town that year, the leaves were just beginning to fall, they trickled past the long high school windows in the waning afternoon light — Edna Belle stayed behind to work with Miss Benson on the layout for the school magazine which was called Whispers , and which Edna Belle hoped to serve as art editor next term. The art editor this term was a senior named Phillip Armstrong Tillis, who was very talented and who had drawn both the cover of the magazine as well as the end papers, and who Edna Belle had dated once or twice and who, frankly, she was really crazy about. He was not a very good-looking boy, his nose was too large for his face, and he wore eyeglasses, but he had a wonderful sense of humor and a crazy way of looking at things, very offbeat and cool ("I used to have this little turned-up button nose," he once said, "but I had an operation done to make it long and ugly") and she loved being with him because he was always thinking up nutty things to do, like pulling into Mr. Overmeyer's driveway to neck one night, instead of going over to the hill near the old burned Baptist church that had been struck by lightning. When Mr. Overmeyer came out to see what was going on, Phillip Armstrong got out of the car and bowed from the waist and said, "Good evening, sir, we were wondering if we might park here for a few moments to discuss a matter that's of great importance."

"With me , do you mean?" Mr. Overmeyer asked.

"No, sir, the young lady and I wished to discuss it privately."

Mr. Overmeyer looked so relieved that (A) it wasn't some hoods from Connors who were looking for trouble, that (B) it wasn't some crippled war veterans selling magazine subscriptions, and that (C) he personally would not have to get involved in this discussion, whatever it was, that he mumbled, "Sure, certainly, go right ahead," and then went back into the house and drew the blinds to assure Phillip Armstrong of the privacy he wanted. They had necked up a storm that night, and she had let Phillip Armstrong touch her breast right there in the driveway, but only twice.

The reason Phillip Armstrong wasn't there that November afternoon to help with the layout was that he had come down with the mumps, of all things ("You know what that does to a grown boy, I suppose," Cissie said) and was home in bed. It was just as well because if Phillip Armstrong had've been there, then Edna Belle and Miss Benson wouldn't have talked, and Edna Belle's whole life wouldn't have changed. In looking back on the conversation, Edna Belle couldn't remember exactly what they'd said that was so terribly important, what they had discussed in such personal terms, this woman and her sixteen-year-old student there in the gathering gloom of a high school classroom, the light fading against the long windows, the empty desks stretching behind them, and the smell of paste on their fingers, and snippets of shining proofs clinging to their hands, the drawn pencil lines on the blank pulp pages, the long galleys from the editorial staff, and the careful selection of a rooster drawn by Annabelle Currier Farr and something called Monsoon by a freshman named Hiram Horn, the proofs spread out on Miss Benson's desk top, "There, Edna Belle," and "There," and "How's that?" completely absorbed in the work they were doing, Miss Benson finally snapping on the desk lamp, and the warm circle of light flooding the dummy as the magazine began to take shape and form, the colored pencils sticking out of Miss Benson's hair and reflecting light. Whispers, they whispered now, the school was empty, but what did they say, after all, that had not been said a thousand times before? What was there in Miss Benson's impromptu and heartfelt talk that was not cliched and hackneyed and shopworn and, yes, even trivial? It had all been said before, there was the tinny ring of half-truth to it, and whatever importance it seemed to possess at the time surely came only from the dramatic setting, the classroom succumbing to dusk, the desk lamp being turned on, the young girl listening while the older woman earnestly and sympathetically talked to her about life and living, about pity and understanding, about art, and about love. All of it said before. And better, surely, so very much better than old Miss Benson could ever have said it even if she were skilled with words, which she was not, even if she were half the gifted artist Edna Belle supposed she was, which she was not. All of it said before.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Paper Dragon»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Paper Dragon» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Paper Dragon» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.