Sir Philip was there, paying his daily duty call upon his aunt; he acknowledged Catherine with a nod and a smile, which she returned, still grateful for his kindness of the previous evening.

Mrs. Findlay was berating her sister-in-law. “It had to be Laura-place, did it not, Agatha? No Queen-squares for you, ma’am! And my poor brother not cold in his grave. ’Tis not enough that one of you disposed with him, but you must revel in it by making merry with his fortune!”

“I am sure that I do not know what you are talking about, Fanny,” said her ladyship; though her blush did not escape Catherine’s sharp eye.

“I believe you do, Agatha; I know one of you does. You,” she said, looking at Sir Philip, “or you,” turning a glare upon her niece.

“What are you suggesting, madam?” asked Sir Philip, his voice low and dangerous.

“I suggest nothing, sir; I state it for all to hear. I am come to Bath to determine which of you murdered my brother.”

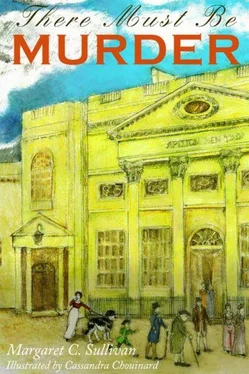

Chapter Six

Murder and Everything of the Kind

Mrs. Findlay’s words shocked all present into silence.

“Really, Fanny,” said Lady Beauclerk in a faint tone of voice. “You must be reading horrid novels to imagine such a thing. Poor Sir Arthur, murdered! After he suffered so! I am sure that no man could have been more tenderly nursed by his wife and daughter.”

“Giving you the perfect opportunity to assist his exit from this world. And you,” said Mrs. Findlay, rounding on Sir Philip, “always hanging around and ingratiating yourself with the old man. You did not think he would hear about your unsavory adventures, did you? You are fortunate he did not cut you out of the will!”

“Beaumont is entailed,” said Sir Philip. “Whatever my uncle thought of me — and I think, and hope, he thought well — he did not have the power to disinherit me.”

“From the title and the estate, perhaps not; but what of the funded monies? I know of a few provisions in the entailment that would have put you in a very uncomfortable situation indeed: master of a great estate, and unable to afford to run it!”

“There was no reason for my uncle to change the provisions of his will,” said Sir Philip with a touch of impatience.

“No reason? After the way you carried on in Brighton last summer? To think I would live to see a Beauclerk involved in a criminal conversation!”

Catherine was paying little attention to the argument between Sir Philip and his aunt. She was thinking over everything she had learned that afternoon: that Sir Arthur’s sister thought his death had not been natural; that both Lady Beauclerk and her daughter had private, secret access to strong poison; and that the apothecary who provided Miss Beauclerk with that poisonous potion had tended Sir Arthur in his last days. A younger Catherine might have reached a most alarming conclusion indeed; but as Henry had once bid her, she now consulted her own sense of the probable. It did not seem possible that a man such as Sir Arthur Beauclerk, tended by a retinue of servants and physicians, could be the victim of a murderous plot; but the Beauclerks were an unhappy family, and who could tell to what measures the desperate might resort?

Sir Philip, mistaking Catherine’s thoughtfulness for distress, or perhaps just embarrassed that an outsider was witnessing the incident, said, “Mrs. Tilney should not have to listen to this.”

Mrs. Findlay whirled about. “Tilney! I have heard that name. You may tell General Tilney, madam, that he is in my sights as well. Sniffing round the widow before my poor brother had been dead half a year! I dare say that fancy Abbey of his costs a pretty penny to run. He’ll have a mind to your jointure, Agatha, you may depend upon it.”

“That is enough, aunt,” said Sir Philip. He crossed the room to where Catherine stood and took her elbow. “Let me procure a chair to take you home, ma’am.”

“Yes, let Philip help you,” said Miss Beauclerk. “Thank you for coming out with me this morning, Mrs. Tilney, and I hope to see you tonight at the theatre.”

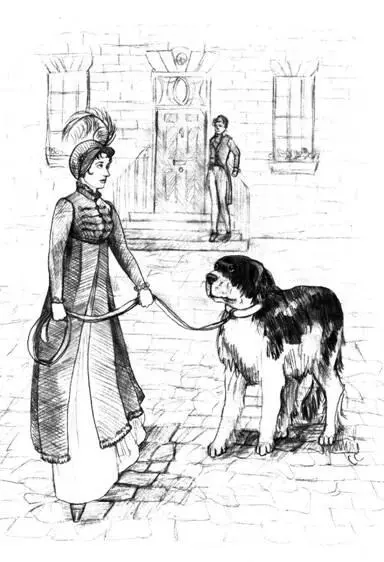

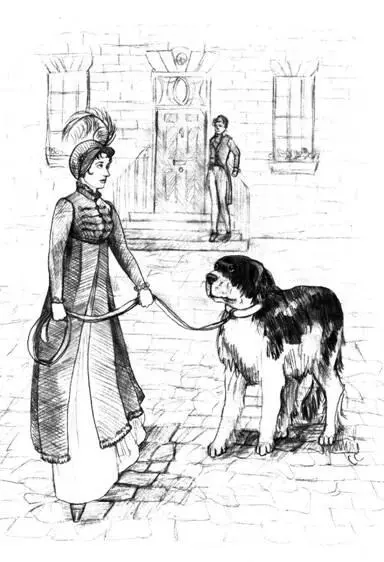

Catherine hastily took her leave; Sir Philip escorted her down the stairs and waited with her while the footman went off to fetch MacGuffin.

“May I get you a chair?”

“Oh, no; my lodgings are just a few steps away, and I have my dog.”

“One of the footmen could bring your dog to your lodgings, and you are distressed by my aunt Findlay’s nonsense. Pray let me procure you a chair.”

“Oh, I am not distressed,” said Catherine.

He looked at her closely. “Are you not?”

“No, sir; I am perfectly able to walk; but is very kind of you to think of it.”

“Most women would have a fit of the vapors at overhearing such an extraordinary declaration as my aunt’s. I salute you, Mrs. Tilney.”

Catherine smiled and blushed as the footman returned, leading MacGuffin.

Sir Philip looked at the Newfoundland and said, “Good Lord. No, you need no chair, Mrs. Tilney; you could ride this fellow home.”

Catherine considered this. “Henry talks of training him to pull a little cart to give rides to the children of our parish. But that would not do for me.”

Sir Philip smiled. “Indeed not, madam; though he is a handsome lad.” He bent to pet MacGuffin, but the dog pressed against Catherine and made a sound somewhere between a snort and a growl.

“For shame, Mac!” cried Catherine. “Sir Philip means me no harm.” MacGuffin looked up at her with sorrowful eyes. To Sir Philip she said, “He really is a very good-natured creature in general.”

“He probably caught a scent of Lady Josephine upon me. That deuced creature will get my coat all over hair when I call upon my aunt.”

“Yes, that must be the case. Good day, Sir Philip, and thank you again for your kindness.”

“It was my pleasure, ma’am. Did I hear my cousin say that you would be at the theatre tonight?”

“Yes, Lord Whiting procured a box and invited us to join him.”

“May I look forward to the pleasure of visiting your box between acts?”

Catherine was unsure of the proper response to such a proposal. “Why — yes, I dare say his lordship will not mind.”

“That is very good of you to say.” He raised her gloved hand to his lips. “Until tonight.”

Catherine, blushing at such attention, hastily said good-bye and left the house. As she reached Pulteney-street, she could not help looking back; Sir Philip still stood in the doorway of his aunt’s house, watching after her with a little smile.

***

The maidservant had just placed the final touches on her hair when Henry entered Catherine’s dressing-room. He surveyed her with pleasure. “Very lovely, my sweet. Whiting and Eleanor join us for dinner; I saw them at Milsom-street, and did not think you would mind.”

“No, of course not.” She dismissed the maid and turned to Henry eagerly. “What did your father say?”

“As we suspected, he is considering marriage with Lady Beauclerk, but has made no declaration.”

“Will he, do you think?”

“I cannot say; I do not think he knows his own mind.”

Catherine had a brief struggle with her conscience, trying to decide if she should tell Henry about the scene in Laura-place; but since General Tilney was involved, she reasoned he would hear about it soon enough. She related her adventure of the afternoon: the visit to the apothecary, Miss Beauclerk’s beauty potion, her aunt’s accusations. At the end, Henry looked thoughtful.

Читать дальше