An elderly man in a frizzled wig and a green baize apron like Mr. Shaw’s emerged from the back of the shop, followed by the protesting Mr. Shaw.

“Introduce me to the lady, Ned, there’s a good lad,” said the older man.

“Miss Beauclerk,” said Mr. Shaw in tones of resignation, “may I present Mr. Walton?”

“I’ve been compounding since long before you were born, ma’am,” said the older man earnestly, “and I’m here to tell you that these beauty potions you young ladies will take do you no good, ma’am, you mark my words. They may make your skin white for a time, but the arsenic builds up in the humors, and poisons you in the end. You look like a good girl; you’ll listen to old Sam, you will, and leave off this potion.”

“Arsenic?” cried Catherine in alarm. “My dear Miss Beauclerk — you take arsenic?”

“It is trace amounts, ma’am,” said the harassed Mr. Shaw. “Not enough to harm anyone, I assure you; just enough to freshen the complexion; I would never harm — ” he broke off, confused.

Mr. Walton was much amused by his lackey’s confusion. “Oh, yes, that’s right, Neddy. You understand. You won’t let the young lady poison herself. If it’s a fresher complexion you’re seeking, miss, I recommend a bit of Gowland’s Lotion. For a patent potion it’s very effective; apply it every day, and keep out of the sun, and your skin will stay white and soft without the poison. You listen to old Sam.”

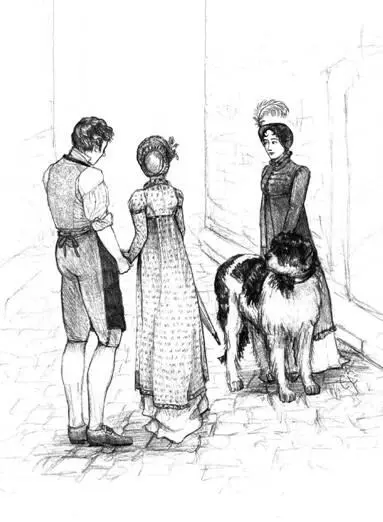

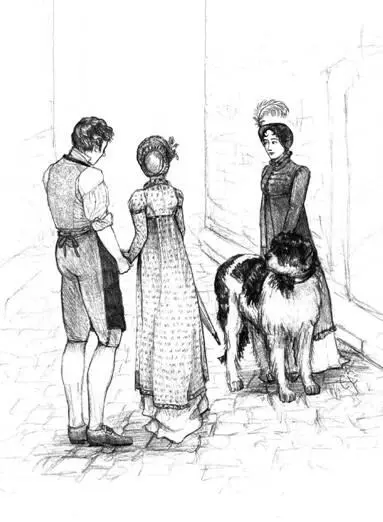

“Come, Mrs. Tilney,” said Miss Beauclerk coldly. “If we cannot procure the item we seek here, we must find it elsewhere.” She left the shop immediately, Catherine and MacGuffin following hastily behind.

They had not got far when they heard running footsteps behind them. MacGuffin pressed against Catherine’s legs and turned back to face their attacker; but it was only Mr. Shaw. He seized Miss Beauclerk’s hand. “Judith,” he said, “I have been in hell since I came here. You see the depths to which I have fallen.”

“I wonder why you stay there, then; I thought you came to Bath to open your own establishment.”

“I will require much more than I thought to set up my own shop. I am working at Walton’s only until I save enough — only a few more months, I swear it. Then I will be my own man. And now that our obstacle is removed — ”

Miss Beauclerk gave Catherine another conscious side-glance. “No! No, sir, do not speak so. My mother would not allow it, any more than my father did.”

“You are of age, Judith — ”

“I would be cut off from my family, and all good society. Do not ask this of me, sir. You know I have not the courage.”

Mr. Shaw’s handsome head drooped over her hand, still held tightly within his own. “Will I see you at the theatre tonight, at least?”

“Yes, we will be there.”

“May I sit with you?”

“You know that is not within my power.”

“But you will slip away and meet me, then?” His voice lowered. “I shall bring your potion.”

She sighed and gave a little toss of her head. “I shall try.”

He raised her hand to his lips and kissed it with violent affection. “Do I have your promise, my love?”

“Yes. Yes, you have it. Just be sure to bring the potion.”

Catherine thought a lover should look happier to make an assignation than Miss Beauclerk looked at the present moment, but she had not had experience of such clandestine romance before; nor of a gentleman who made love to a lady in the street, in front of several interested loungers and passersby.

“Until tonight, then.” He bobbed a sort of bow at Catherine and hurried back towards the shop.

As they walked back to Laura-place, Miss Beauclerk seemed inclined to be quiet, and Catherine allowed her to be so. Finally she said, “Mrs. Tilney, I must ask you a favor; on such a short acquaintance as ours, I have no right; but I pray you will not mention this to my mother.”

“Yes, I suppose she might worry if she knew about your tonic.”

Miss Beauclerk looked her surprise. “She knows about my tonic, and what it contains. She uses something similar herself. It was due to her influence that I asked Mr. Shaw to provide it. Mother has her own supplier. But I meant meeting Mr. Shaw. She does not quite approve of my seeing him. I did not intend to — but it is too late for that. I pray you will not mention it.”

Catherine promised that she would not as they entered Laura-place.

“Will you come in for a moment?” asked Miss Beauclerk. “You may take leave of Mamma, and let her know that I have not been wandering the streets of Bath alone, and getting into mischief.”

Catherine thought her request rather extraordinary, but did not know how to refuse it.

They arrived at the door of Lady Beauclerk’s house at the same time that a dowdy chaise, drawn by a pair of shaggy horses, drew up. An elderly servant in well-worn livery climbed down heavily from his perch and, seeing Miss Beauclerk staring at him, waved and grinned toothlessly.

“Oh, Lord,” said Miss Beauclerk under her breath.

Catherine looked at the servant curiously. “Who is that?”

“He is my aunt Findlay’s man. Well, Mrs. Tilney, it seems that you will have the opportunity to meet one of the more eccentric members of my family, arrived with her usual fortunate timing just as we thought to pass ourselves off creditably in Bath.”

Catherine, unsure how to respond, said, “I have a great-aunt who likes to read me lectures.”

“Then you understand what it means to have a relative whose main purpose in life is to mortify one.”

The servant opened the chaise door and let down the steps, and his mistress emerged: a woman tall and solidly built, with a great beak of a nose and a long chin to match. She looked up at the house and said, “Of course she took one of the grandest houses in Bath. Such unwonted extravagance! But that is your mother all over, Judith. What my poor brother would have thought of it, I am sure I do not know.”

“Good day, aunt,” said Miss Beauclerk.

“Good day, indeed! Do not think I have not heard what you all have been up to, aye, and that ne’er-do-well nephew of mine, too. I have my informants, miss.”

“I am sure you do, aunt.” Seeing how Mrs. Findlay stared at Catherine, she added, “May I present Mrs. Tilney to your notice?”

“Tilney, eh? I have heard that name, oh yes indeed. I know what your set is up to.” Mrs. Findlay swept past both ladies and the footman who held the door. “I trust I need not send up my card; I trust the dowager will see her poor widowed sister.”

“Oh, dear,” whispered Miss Beauclerk. “Mamma will not like it if my aunt insists on calling her ‘the dowager.’”

“Perhaps I should just go back to our lodgings,” said Catherine.

“No, no; Mamma will take it amiss if you do not come up, just for a moment. Pray do, ma’am.”

Catherine could not resist a supplication made with such softly pleading eyes; and she was herself interested in seeing her ladyship’s reaction to being called “the dowager.”

The footman said to her, “Begging your pardon, ma’am, but your dog looks like he could use a drink of water. I can take him to the kitchen if you like.”

Catherine looked at MacGuffin’s hanging tongue and agreed, and the Newfoundland padded down the hall behind the footman as the ladies climbed the stairs to her ladyship’s sitting-room.

Читать дальше