To Anne L. Groell, without whose enduring belief in this book, it would never have been written.

And a special thank you to John Kaiine and Beryl Alltimes, for invaluable insights.

You, my creator, would tear me to pieces and triumph; remember that, and tell me why I should pity man more than he pities me?

Frankenstein , MARY SHELLEY

It should be noted Loren’s titles for her second and third part derive from the works of the marvelous Tennessee Williams and William Blake, respectively.

PART ONE

The Train to Russia

CHAPTER 1

What do you do about a story that has a beginning, a middle, and an end—and one day you find that the ending has altered—into a second beginning?

You’re not going to like me.

I apologize for that.

It was Jane; she was the one you liked. I liked her, too.

And I—am not Jane. Not in any single way. But one.

And that one single way is perhaps the only thing you and I also have in common.

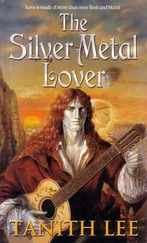

Because if we liked Jane, we loved Silver.

Didn’t we.

The temptation is to start this just as Jane did, with a description of my early life, and where I lived. Jane’s mother was rich, and some of what Jane described might have been predictable—the travels, the house in the clouds. Even the way Jane came into existence—that was, selected, carried physically for five months, taken out very carefully, brought to full-term, and then nursed by machines—the Precipta method. But I was just born. I was a mistake. My mother made that very clear, apparently, when she dumped me ten months later on Grandfather.

I say Grandfather. He wasn’t. He was the man my mother had herself lived with when she was a child. He had sort of brought her up, but then turned her out on the street when she was fifteen. He was a believer in the Apocalyte religion, and was pretty strict, and my mother was always in trouble of some sort—drink, drugs, legal and otherwise, men. When she gave me to him, she contemptuously told him, “Maybe you can do better with this one.” The Apocalytes were “charitable.” So they took me in. That was the first eleven, twelve years of my life, then, that gray-white wreck of a house on Babel Boulevard.

It was quite tough there. First the babies’ room, which I don’t remember. Then about twenty girls all ages in one dank dormitory. The roof leaked in the rain, and in summer you could hardly sleep for the scratching and shuffling of rats in the walls. Three grim, frugal meals a day in the communal hall. Lots of prayers. God was a wonderful being who wanted us to love him and sent us not only irresistible temptations we must ignore, but horrible mishaps—sickness, poverty, earthquake, and fire—to see if we would still do it. But if we did fall out of love with God, God got upset, and then he would make us burn in Hell forever. I swallowed all this along with the awful food. What else did I know? After all, the Big One was coming soon, the Day of Wrath, when the Asteroid, captured between Earth and moon about two decades before, would crash into the Earth and destroy us all, which is what had nearly happened previously. Whenever we strayed, Grandfather would take us up on the dodgy roof by night and show us the Asteroid, rising blue-green and molten over the slums. “Behold the eye of God’s Destroying Angel,” announced Grandfather. Hey, guys, you bet we tried to be good.

There were tremors once or twice, too, (quite a bad one when I was five) to help remind us. Quake-sites still existed all over the city, except in the richest areas, where they had been put right after the initial disturbance.

I suppose, growing up with this, I got used to it. Life was simple. Obey Grandfather, love God, wait for the Day of Wrath when we—the righteous ones—would be swept to Paradise on golden wings. Did I believe in Paradise? Perhaps. No, not really. Strange, maybe. I believed in all the bad things—Hell, punishment, an insecure and vengeful deity—but not in that.

There was a much larger earthquake when I was nine. It happened just before dawn. I remember waking—cold, there was snow on the ground—to hear the usual small tremor stuff, creakings, grunts of timber and brick, the shift of powder-dust dislodged and falling—and that rumble under the bed like a truck was revving up right outside. Oh, it’s a tremor, I thought, and nearly went back to sleep. But then the rumble rose to a bellow, the mattress leapt, and part of the wonky ceiling dropped into the dorm and landed with a crash between the beds. Something even hit my legs—bounced off—I wasn’t hurt. The girls started screaming then. Me, too. We pelted out of the room and tried to go downstairs, but some of the staircase had come apart. So someone said we should crawl up the swaying upper steps to the other end of the roof, the sounder reinforced area over Grandfather’s room.

When we’d gotten up there—I’ll never forget the roar and boom that was surging out of a city gone almost black but for the sprays of appalling lights like fireworks, which were flyer cables snapping, and power and electricity wires breaking and catching on fire. And next it was brighter because the sun was coming up, but also a couple of buildings were alight. Was it now ? Was this it ?

Then everything settled with a disgusting grinding crump. And Grandfather appeared up the fire escape, which was somehow still in one piece. Plaster dust in his iron hair only made him more apocalyptic. He led us at once in prayers of thankfulness to God, who had spared us even while he chastised the unholy city.

We were put on the lower floor for months, above the boys’ dormitory, where there were only three or four weedy male kids, until some members of another house of the Order finally came and fixed the stairs and the roof a bit. Then we moved back to our own dorm. We couldn’t sleep for a long time—too scared—but we were mostly children, and in the end we did. The aftershocks were slight, but a great deal of damage had been done in the city from the new quake.

A week after the quake anyhow, I was ten. My birthday was marked by a solemn blessing, and I had the special birthday privilege of washing the others’ feet.

It was next year that I found the Book.

It was my week for washing dishes and I was down in the basement, doing just that. Outside it was dull and close, thundery, and through the very tops of the windows all I could see was a jagged line of brassy overcast above a broken wall. The water heater didn’t work properly (not auto), and half the time I had to boil jugs on the nonauto electric stove. I was very hot and yawning so much with tiredness and boredom, I was nearly insane.

Then, crossing back to the stove for yet another jug, I trod on a slab of floor that shifted under me. I yelled, but there was no one else to hear. I thought the floor was giving way and I was going to fall down into a (Hellish?) abyss. But it wasn’t that at all. When I righted myself, I saw that only a small square part of the floor had tilted, revealing a small dark slot beneath.

I—and countless others—had stumped over that floor a thousand times and never disturbed it. But one of the recent minor tremors must have loosened something, some glue or padding that had been used to close the little hatchway tight. And now it had only taken my narrow just-eleven-years-old foot, with about sixty-six pounds behind it, to tip the hatch open.

Читать дальше

![William Frith - John Leech, His Life and Work. Vol. 1 [of 2]](/books/747171/william-frith-john-leech-his-life-and-work-vol-thumb.webp)

![William Frith - John Leech, His Life and Work, Vol. 2 [of 2]](/books/748201/william-frith-john-leech-his-life-and-work-vol-thumb.webp)