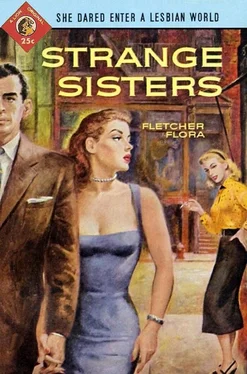

Флетчер Флора - Strange Sisters

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Флетчер Флора - Strange Sisters» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1954, Издательство: Lion Books, Жанр: Эротические любовные романы, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Strange Sisters

- Автор:

- Издательство:Lion Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1954

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Strange Sisters: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Strange Sisters»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Here is the story of a lesbian, and of the devastating crime to which she was driven when she tried to disavow her body’s urgings. Here is a shattering theme, treated with rare sensitivity and power.

Strange Sisters — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Strange Sisters», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Good afternoon, Dean.”

Relieved, Vera completed her crossing of the campus. She felt light and vigorous, strangely uplifted. Her mood was, in fact, almost manic. She would not think of the awful episode of fear from which she had escaped. She would never think of it again. It was true that the fear, the remembrance of it, was still perilously near the surface of her consciousness, still broke the surface briefly at odd times, but she was quite adroit at the technique of repression. In time she would bury it.

In her house, she fixed herself a cup of tea and carried it into the living room. Her little group was meeting later, and she hoped the conversation would be stimulating. While she was waiting, it would be pleasant to listen to some music.

She went over to the console phonograph and adjusted the mechanism. The lilting music of Chopin was released in the room.

Jacqueline Wieland sat on a tall stool under ersatz stars and drank a daiquiri. She had almost ordered a Sidecar before she recalled at the last moment that she had decided not to drink Sidecars any more. She had also decided not to patronize the Bronze Lounge any more, for that matter, but she had reversed the decision. She had done so because she understood that it was dangerous to defer to ghosts, to allow her thoughts and actions to be regulated by irrational fear of certain associations.

It had been a difficult day at the store — a series of minor problems terminating with another irritating conference with the old fool from Furniture. But actually, she supposed, the day had been no more difficult than the average. It was just that she had been abnormally sensitized to any emotional impact, however trivial in nature, by the deadly threat to the structure of her life that had just removed itself. She was like a person who had just recovered from pneumonia and had to protect himself from every petty exposure. There had even been trauma in her escape, in the sudden release from fear, for it is, after all, a rather frightening and shattering experience to realize that you are capable of feeling a fierce, unholy joy in someone’s death.

She finished her daiquiri and thought that she would have another. The bartender appropriated her empty glass, and she nodded to indicate a refill. Sitting on the stool with her hands lying in her lap, feeling more relaxed than she had felt at any other time since the instant of the radio newscaster’s announcement and her own instantaneous reaction of terrible relief and joy, she watched the bartender measure ingredients into an electric blender. He was a small man with a tired face and a shining bald head, and he conducted his business with the bored, assured economy of motion that comes from long familiarity with simple routine. Placing a clean glass on the bar before her, he poured from the container of the blender and then moved away to resume an interrupted conversation with a beer drinker two stools down. Her attention followed him idly, enlarging to include the sense of his words to the beer drinker, and after the first words, she wished that it had not, that something had diverted it in time, or that she had left after the first daiquiri.

“Like I was saying,” the bartender said to the beer drinker, “she was in here that evening, the evening before the day it came out in the papers about her being suspected of knifing this guy. She was drunk, all right, really drunk, but somehow not drunk like the standard lush. It was more like she was drinking to get away from something. That’s what I thought at the time, and now I can see it was true. She kept drinking straight rye and talking crazy as hell, but it was more than the rye talking, it was something behind the rye, something on her mind that was driving her nuts. She kept saying things about her hair, the color of it, how the color was wrong and how God must love me because He made me bald, and finally she said something about the empty cup of the world.”

“Jesus,” the beer drinker said.

“Yeah. It made a guy feel kind of queer to hear it.” The bartender looked down at the bar and shook his head, remembering. “I finally got her into a booth and got her a cup of black coffee, but then she just got up all of a sudden and walked out. She left her purse behind in the booth, and I put it away, thinking she’d be back for it, but then the very next day, like I said, it came out about her being suspected of murder, and so I called the cops, and a snotty lieutenant named Ridley came around to pick it up. I told him all this that I’m telling you, and he just stood and listened as if I were passing the time of day, and after I was finished he said okay, just to forget it, and he walked out with the purse without so much as a go to hell. Maybe he didn’t figure a bartender could have any sense, or he wouldn’t be a bartender, and he might be right, at that. Anyhow, the dame cut off all of her hair that same night and took a handful of sleeping pills, so I guess there was some kind of crazy meaning in what she said, even if he didn’t think so.”

“Psycho,” the beer drinker said. “I was reading in a magazine that there are more psychos now than ever before. It’s the pressure. Too much pressure on everyone.”

The bartender kept on looking at the bar and shaking his head. He said slowly, “I don’t know. There was something about her. Something kind of young and all mixed up. I felt sorry for her. I keep thinking that she was looking for help, trying to find someone to help her, and there wasn’t anyone, not anyone in the world.”

It was then that Jacqueline left. Outside, she stood on the curb and waited for a taxi to come along, a tall and striking woman, beautifully and severely groomed and tailored. In the grace of her posture and the tilt of her head, there was pride and a certain arrogance. The taxi driver who finally responded to her signal thought she was real class, the kind of dame you saw once in a coon’s age.

Lieutenant Ridley sat in his office and watched three sparrows.

There was one window in the room that overlooked a narrow brick alley. The window was recessed about eight inches in the wall of the building, leaving an outside sill wide enough for the accommodation of birds. Sometimes pigeons sat on the sill, but this afternoon three sparrows had assumed possession, and they had been sitting out there for a long time. They sat in a row so precisely spaced that it seemed someone must have measured the distance between them. Occasionally, one of the sparrows would stir and stretch its feathers, but none of them ever signified any serious intention of flying away. Ridley knew that this was true because he had been watching them. He had started watching them at four, and it was now five, and he could guarantee that the same three sparrows had been there all the time.

He was thankful for the company of the small, gray birds. He sat in his chair with his back to the desk and the door and wondered why this was. Perhaps, he thought, it was because they were birds of no importance, just drab little bits of life that were harbingers of nothing. When you’d descended the social strata of birds to the sparrow, there just wasn’t any place lower to go. That was even implied in the scriptures. When the scriptures said that God marked the fall of the sparrow, it was supposed to indicate the ultimate in concern and compassion. If a lousy little sparrow got consideration, there was plenty for everyone. Back home, the kids around the neighborhood had called them sparkies and had shot them with B-B guns. He’d never owned a B-B gun himself. He’d never enjoyed killing anything until, for a short while between then and now, he’d learned to enjoy killing men.

Someone came into the room behind him and sat down. Without turning around to see, he knew by the pace and weight of the tread that it was Tromp. He waited for Tromp to speak and wished that he wouldn’t.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Strange Sisters»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Strange Sisters» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Strange Sisters» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.