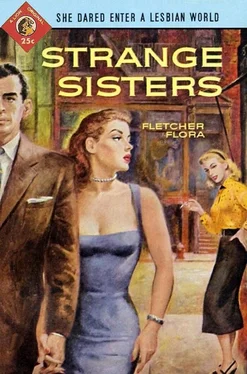

Флетчер Флора - Strange Sisters

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Флетчер Флора - Strange Sisters» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1954, Издательство: Lion Books, Жанр: Эротические любовные романы, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Strange Sisters

- Автор:

- Издательство:Lion Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1954

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Strange Sisters: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Strange Sisters»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Here is the story of a lesbian, and of the devastating crime to which she was driven when she tried to disavow her body’s urgings. Here is a shattering theme, treated with rare sensitivity and power.

Strange Sisters — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Strange Sisters», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Fletcher Flora

Strange Sisters

Chapter 1

From the start, she knew it was a bad thing she was doing. Of all the things she had ever done that were bad for her, which were far greater in number than she could remember or wanted to remember, this was probably the worst and would bring her after a while to the worst end.

The irony was that it was something she wanted to turn out good, and she had only started it in the first place because of her sudden conviction that there had to be a break, and that once the early and really bad part of it was over with, everything would get better. Not immediately, of course, not all at once, but slowly and surely over a period of time, the way she’d seen daylight come after one of the long nights when she hadn’t slept.

But she had understood, once it was begun, that the bad part of it was all of it, the beginning and the end of it, and that nothing would ever get better. She thought a thousand times that she would stop, would go no farther with it, but she went ahead in spite of knowing very well that it was coming to a bad end, because after she had gone so far, she was obsessed with the belief that any kind of end was better than no end at all.

It was so simple, really, and involved nothing more than a man. An ordinary man. Well, maybe not such an ordinary man, at that, as anyone might have felt after seeing his lean, gray, hawk’s face. Not that she had chosen him because he was either ordinary or extraordinary. She had not really chosen him at all. She was merely using him, and she was doing it because he had presented himself at the right time under the right circumstances when she just happened to be ripe for him. She had gone into a bar. She had gone there, not to pick up a man, but to get a drink. She had just ridden downtown on a crowded bus, caught in a jam at the rear between a fat man sour with yesterday’s sweat and a younger, thinner man who made the most of the congestion, and she needed the drink badly. She went into the bar and ordered a Sidecar, which was what she usually drank, except when she drank straight rye in order to get quickly and mercifully drunk. She drank the Sidecar greedily, feeling a partial interior recovery and a little warmer in the flesh as the chill drained out.

The man on the stool beside her said, “May I buy you another?”

She had hardly noticed the man when she sat down, and now she looked at him swiftly, her eyes dilating and her viscera reacting with the familiar exorbitant violence that was like a physical shock. She averted her eyes, looking back down into her empty glass, and said with a kind of prim abruptness, “No, thanks.”

The man lifted a hand in a gesture to the bartender. “The lady will have another of the same,” he said.

She didn’t look at him again directly, but she lifted her eyes to probe the smoky depths of the mirror behind the bar and found his face beyond and a little above a row of Pilsener glasses. He was looking at her and smiling, and she noticed this time the strong, hooked nose, the hard, gray planes of the cheeks, the thin, predatory mouth above a narrow, jutting chin. It was not a handsome face, was actually ugly; but it was possessed of a cruel strength, and, rather paradoxically, she found the strength soothing, a kind of depressant to her furious adrenals.

“I said, no thanks,” she said.

His smile spread in glass. “I heard you. Now that you’ve made a gesture for propriety, you can enjoy your Sidecar.”

The bartender placed it in front of her, and after a moment she picked it up and cupped her hands around the small, cold bulb of the glass, letting her eyes slip down from the reflected hawk’s face to the suggestion of her own in amber. She wet her lips with the mixture, permitting a little to slip past and down her throat, and it was then that she got the idea. It just came into her mind. At first it made her slightly sick, and she tried to repel it, but then she accepted it and considered it coldly, looking down into her glass as if the idea had materialized and was there in suspension. She couldn’t have said why she was so suddenly capable of doing it. Yesterday she wouldn’t have been, and tomorrow she probably wouldn’t be. And maybe that was the reason. Because it was time, high time, and it had to be done now, at this moment, in this bar, with this man, or it would never be done at all, because all other times for the rest of her life would be too late. She didn’t actually think it all through like that. It was just a feeling. Maybe it was insight.

“My name is Brunn,” he said. “Angus Brunn.” And even his name was a precipitant. She liked the chopped quality of it. Especially the rugged Angus. It was conservative and agrarian, and it would go with a man who adhered to restrained and traditional forms. All of which was, in this case, a monstrous deception that she practiced on herself deliberately in a kind of inverted hatred.

“Mine is Kathryn Gait,” she said. And then, with the first concession to familiarity that was a sign of fatal commitment, she added, “My friends call me Kathy.”

That’s the way it started, the bad thing. She allowed Angus Brunn to buy her two more Sidecars, and the brandy helped her to do what was necessary. Once when her left hand was lying on the bar beside her glass, he reached out and covered it with his own. His hand was square and hard, with black hair growing in thick clusters between the second and third joints of the blunt fingers, and she felt a sudden shock of sickness in her stomach, a shriveling of the flesh on her bones. She thought then that it was no use, that she would never be able to go through with it, but somehow she managed to leave her hand lying limp beneath his, and after a while, with more help from the brandy, she recovered.

It had gone slowly from there. That afternoon she left him in the bar, but she also left her address and telephone number. She had intended going to Jacqueline’s, maybe to spend the night with her, but instead she killed a couple of hours in a movie and returned to her own place uptown to spend the night alone. Ready for bed, she stood for a moment to examine herself in the full-length mirror on the back of her closet door, leaning forward to trace with her eyes the lines of the face that was almost as lovely as Stella’s had been, the longer lines of the body that even Stella’s had not surpassed. Crossing her arms beneath her breasts, she hugged herself in a fierce, protective gesture of love. She always loved herself in a mirror. Then she wanted to be only what she was, never anything else, and she was able to discount her recurring depression, the suicidal despair and inverted hate.

The next day, Angus Brunn called her, and the first moment was a critical one. Hearing his voice and knowing that the idea she had examined in a Sidecar was gaining shape and dimension, she felt a terrible compulsion to cradle the instrument without answering. But in the end she talked, she let him come, and the idea grew materially over a period of time that seemed ages to her but was actually no more than a week. And now, tonight, in the night club, in the taxi, in the ascending elevator, she understood that it had grown to its ultimate monstrous proportion, and that it was, in spite of her desperate good intention, a bad thing, the worst thing for herself that she had ever done.

In the hall, he unlocked the door to his apartment and pushed it inward. “Welcome to my sanctuary, baby,” he said. “I warn you, you won’t find an etching in the place.”

She accepted this as a bald statement of intention, and she felt her flesh crawl, sucking in her breath in brief anguish at the sharp contraction of her stomach. She had no reason to take offense, certainly, and even less to be alarmed. The intention had been implicit in their relationship from the start, was indeed the whole reason for her allowing the relationship to exist, and she had accepted the essential with a cold, sacrificial despair that now threatened to disintegrate in terror.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

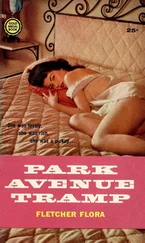

Похожие книги на «Strange Sisters»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Strange Sisters» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Strange Sisters» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.