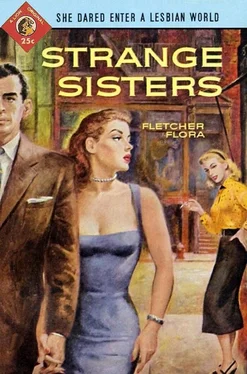

Флетчер Флора - Strange Sisters

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Флетчер Флора - Strange Sisters» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1954, Издательство: Lion Books, Жанр: Эротические любовные романы, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Strange Sisters

- Автор:

- Издательство:Lion Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1954

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Strange Sisters: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Strange Sisters»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Here is the story of a lesbian, and of the devastating crime to which she was driven when she tried to disavow her body’s urgings. Here is a shattering theme, treated with rare sensitivity and power.

Strange Sisters — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Strange Sisters», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She went into the bedroom and sat on the edge of the bed to wait for the dye to set. Now that she had taken positive action to end her trouble, she didn’t mind thinking about things that had happened or might happen, and so she began thinking about what the newspapers and the radio newscasts would say and about the effect of what was said on certain people. She found that this was a great pleasure to her, stimulating a sly, malicious amusement that made waiting easier. For a while she thought about Jacqueline, and then she went back beyond Jacqueline and thought about Vera Telsa. It was certain that both knew by this time that she had been questioned by the police about the murder of Angus Brunn, and it was certain that one of them knew she was guilty. That was not important, though. So far as they were concerned, murder and guilt were minor, and nothing was important or of any consequence whatever except what might be said and become known. And now, at this time, while the possible instrument of their incidental destruction sat on the edge of her bed and waited for her hair to dry, they were feeling the cold fear of the uniquely vulnerable, the grim, oppressive threat of the merciless They.

Sitting there thinking about their fear and how she was the cause of it, she was as delighted as a perverse child. She sat erect, the primness in her posture, and inside she felt rather light and gaseous, and the light feeling, the gas, swelled and gained volume and came up through her throat in the form of laughter. She sat without moving for almost an hour, sometimes laughing a little and sometimes mute as well as motionless, very pleased to think that Jacqueline and Vera were so frightened about something that was not worth being frightened about, because now, of course, since she had discovered this simple way to change herself entirely, she would never do anything bad again, and nothing would happen because of anything bad she had ever done. Being changed, being a different person, she was naturally not responsible for whatever had been done by the person she no longer was.

Eventually it was time to see if her hair was ready to wash. The directions had said approximately an hour. Surely an hour had passed. She got up and returned to the bathroom and peered at her reflection in the little mirror, and she could see immediately that she had again been made the victim of a monstrous joke, and the small tiled room reverberated to the thunderous, rollicking laughter above the lip of the world. For the dye wasn’t going to work after all. She should have known, having had so much experience with the caprice of God, that it would never work. Oh, her hair had changed color, all right, and it was still a bright red-orange to casual observation, but this was only part of the joke, the necessary stimulus of false hope, and she could see in the glass that the real color was already beginning to return and that it could never be altered or disguised, never on earth.

So she would have to destroy it. She knew that now. That which cannot be altered can nevertheless be destroyed. If your eye offends you, pluck it out. The Bible said that. If your hair offends you, pluck it out. Whether it said eye or hair didn’t really matter. It was the idea that mattered. It was the idea of destroying whatever was offensive.

In the mirror, her thin, sad face crumpled and blurred, and she reached up and took her ridiculous orange hair in both hands and pulled as hard as she could. Some of the hair came out in her hands, but only a little, and it was very painful pulling it out that way. She doubted that she could stand the pain. She would probably faint long before she had all the hair pulled out.

Turning away from the mirror, she went into the bedroom and pawed through the top drawer of the chest until she found a pair of scissors. With the scissors, she cut her hair off, doing as she had done with the dye, taking a few strands at a time and cutting them off as close to the scalp as she could. When she was finished, she returned the scissors to the drawer and went back into the bathroom and looked into the mirror again. There was nothing on her head now but a fine bristle over the scalp, and she saw that her scalp was covered with large orange blotches from the dye. She was quite pleased with what she saw. She rubbed a palm over the bristles and laughed into the mirror.

But the hair would return, would it not? Wouldn’t it grow back? Of course it would. Unless the roots were dead, unless you were really bald, hair always grew back. But did it grow back the same color that it was? Exactly the same color? Might there not be a subtle and significant change in pigmentation? Even a little change might make a great difference.

She would know, of course, after it had grown a little, but hair grew so slowly. She had lately waited so often and so long, she was so worn out with waiting, that she couldn’t bear the thought of waiting for this, to see how the hair would come in, if it would be the same or different. Once, when she had been waiting for something, for a time to come, she had taken a sleeping tablet, and waiting had been easy. She had simply wakened to a time that was there.

The sleeping tablets. The little green dragons. What had she done with them? She concentrated, trying to recall where she had put them, and she felt a little foolish when she remembered that they were right in front of her in the medicine cabinet. She had only to lift a hand and open the door and take out the unlabeled box. Having done so, she stood for a moment looking at the tablets and wondering how many she should take, and she decided, since hair grew so slowly, that it would be necessary to take quite a few. It would be necessary, she decided, to take all of them.

Filling a glass with tepid water from the tap, she took the tablets one at a time, swallowing a little of the water after each tablet, and when they had all been taken, she went into the bedroom and lay down on the bed. She was afraid of the dark, of what she might see in it, and so she left the light burning, but pretty soon it began to get dark anyhow, even with the light on, and she was delighted to discover that she saw nothing and was not afraid at all.

Chapter 12

Vera Telsa left the library of Burlington College and walked across the campus toward the street on which she lived. On the way she met the dean. She spoke with crisp courtesy and would have passed immediately if the dean hadn’t stopped. Vera didn’t want to talk with the dean at that moment and resented being forced to do so. She hid her resentment, however, behind a small smile and a faintly deferential attitude.

“I’ve been intending to speak with you, Dr. Telsa,” the dean said. “About this girl who killed the man up in the city and committed suicide afterward. Kathryn Gait, her name was. Such a terrible shock. Of course it’s been several years since she was here, but she was rather a favorite of yours, as I recall.”

Vera’s small smile didn’t waver. “Not particularly. She was a member of my little group of specials, and so I was naturally somewhat interested in her.”

“To be sure. Did you know that your class was the only one in which she made a passing mark?”

“I understood that she made a deplorable showing generally.”

“Yes. Quite an intelligent girl, too. I had nearly forgotten her until this tragic thing happened, and then I went back in the records and reviewed her file. I was forced to dismiss her from school at mid-year, you know. I tried to get her to see Dr. Sandstrom, but she refused flatly. Now, in the light of events, I wonder if I really did all I might have, if I shouldn’t have insisted...”

“You really shouldn’t blame yourself. I’m sure you did all you could.”

“I dare say I did. Certainly I had no idea... Well, I won’t detain you any longer, Doctor. Good afternoon.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Strange Sisters»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Strange Sisters» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Strange Sisters» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.