Peter Siebel - Practical Common Lisp

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Siebel - Practical Common Lisp» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2005, ISBN: 2005, Издательство: Apress, Жанр: Программирование, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Practical Common Lisp

- Автор:

- Издательство:Apress

- Жанр:

- Год:2005

- ISBN:1-59059-239-5

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Practical Common Lisp: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Practical Common Lisp»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Practical Common Lisp — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Practical Common Lisp», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

((A . 1) (B . 2) (C . 3))

The main lookup function for alists is ASSOC , which takes a key and an alist and returns the first cons cell whose CAR matches the key or NIL if no match is found.

CL-USER> (assoc 'a '((a . 1) (b . 2) (c . 3)))

(A . 1)

CL-USER> (assoc 'c '((a . 1) (b . 2) (c . 3)))

(C . 3)

CL-USER> (assoc 'd '((a . 1) (b . 2) (c . 3)))

NIL

To get the value corresponding to a given key, you simply pass the result of ASSOC to CDR .

CL-USER> (cdr (assoc 'a '((a . 1) (b . 2) (c . 3))))

1

By default the key given is compared to the keys in the alist using EQL , but you can change that with the standard combination of :keyand :testkeyword arguments. For instance, if you wanted to use string keys, you might write this:

CL-USER> (assoc "a" '(("a" . 1) ("b" . 2) ("c" . 3)) :test #'string=)

("a" . 1)

Without specifying :testto be STRING= , that ASSOC would probably return NIL because two strings with the same contents aren't necessarily EQL .

CL-USER> (assoc "a" '(("a" . 1) ("b" . 2) ("c" . 3)))

NIL

Because ASSOC searches the list by scanning from the front of the list, one key/value pair in an alist can shadow other pairs with the same key later in the list.

CL-USER> (assoc 'a '((a . 10) (a . 1) (b . 2) (c . 3)))

(A . 10)

You can add a pair to the front of an alist with CONS like this:

(cons (cons 'new-key 'new-value) alist)

However, as a convenience, Common Lisp provides the function ACONS , which lets you write this:

(acons 'new-key 'new-value alist)

Like CONS , ACONS is a function and thus can't modify the place holding the alist it's passed. If you want to modify an alist, you need to write either this:

(setf alist (acons 'new-key 'new-value alist))

or this:

(push (cons 'new-key 'new-value) alist)

Obviously, the time it takes to search an alist with ASSOC is a function of how deep in the list the matching pair is found. In the worst case, determining that no pair matches requires ASSOC to scan every element of the alist. However, since the basic mechanism for alists is so lightweight, for small tables an alist can outperform a hash table. Also, alists give you more flexibility in how you do the lookup. I already mentioned that ASSOC takes :keyand :testkeyword arguments. When those don't suit your needs, you may be able to use the ASSOC-IF and ASSOC-IF-NOT functions, which return the first key/value pair whose CAR satisfies (or not, in the case of ASSOC-IF-NOT ) the test function passed in the place of a specific item. And three functions— RASSOC , RASSOC-IF , and RASSOC-IF-NOT —work just like the corresponding ASSOC functions except they use the value in the CDR of each element as the key, performing a reverse lookup.

The function COPY-ALIST is similar to COPY-TREE except, instead of copying the whole tree structure, it copies only the cons cells that make up the list structure, plus the cons cells directly referenced from the CAR s of those cells. In other words, the original alist and the copy will both contain the same objects as the keys and values, even if those keys or values happen to be made up of cons cells.

Finally, you can build an alist from two separate lists of keys and values with the function PAIRLIS . The resulting alist may contain the pairs either in the same order as the original lists or in reverse order. For example, you may get this result:

CL-USER> (pairlis '(a b c) '(1 2 3))

((C . 3) (B . 2) (A . 1))

Or you could just as well get this:

CL-USER> (pairlis '(a b c) '(1 2 3))

((A . 1) (B . 2) (C . 3))

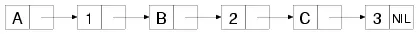

The other kind of lookup table is the property list, or plist, which you used to represent the rows in the database in Chapter 3. Structurally a plist is just a regular list with the keys and values as alternating values. For instance, a plist mapping A, B, and C, to 1, 2, and 3 is simply the list (A 1 B 2 C 3). In boxes-and-arrows form, it looks like this:

However, plists are less flexible than alists. In fact, plists support only one fundamental lookup operation, the function GETF , which takes a plist and a key and returns the associated value or NIL if the key isn't found. GETF also takes an optional third argument, which will be returned in place of NIL if the key isn't found.

Unlike ASSOC , which uses EQL as its default test and allows a different test function to be supplied with a :testargument, GETF always uses EQ to test whether the provided key matches the keys in the plist. Consequently, you should never use numbers or characters as keys in a plist; as you saw in Chapter 4, the behavior of EQ for those types is essentially undefined. Practically speaking, the keys in a plist are almost always symbols, which makes sense since plists were first invented to implement symbolic "properties," arbitrary mappings between names and values.

You can use SETF with GETF to set the value associated with a given key. SETF also treats GETF a bit specially in that the first argument to GETF is treated as the place to modify. Thus, you can use SETF of GETF to add a new key/value pair to an existing plist.

CL-USER> (defparameter *plist* ())

*PLIST*

CL-USER> *plist*

NIL

CL-USER> (setf (getf *plist* :a) 1)

1

CL-USER> *plist*

(:A 1)

CL-USER> (setf (getf *plist* :a) 2)

2

CL-USER> *plist*

(:A 2)

To remove a key/value pair from a plist, you use the macro REMF , which sets the place given as its first argument to a plist containing all the key/value pairs except the one specified. It returns true if the given key was actually found.

CL-USER> (remf *plist* :a)

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Practical Common Lisp»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Practical Common Lisp» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Practical Common Lisp» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.