Peter Siebel - Practical Common Lisp

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Siebel - Practical Common Lisp» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2005, ISBN: 2005, Издательство: Apress, Жанр: Программирование, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Practical Common Lisp

- Автор:

- Издательство:Apress

- Жанр:

- Год:2005

- ISBN:1-59059-239-5

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Practical Common Lisp: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Practical Common Lisp»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Practical Common Lisp — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Practical Common Lisp», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

CL-USER> (subst 10 1 '(1 2 (3 2 1) ((1 1) (2 2))))

(10 2 (3 2 10) ((10 10) (2 2)))

SUBST-IF is analogous to SUBSTITUTE-IF . Instead of an old item, it takes a one-argument function—the function is called with each atomic value in the tree, and whenever it returns true, the position in the new tree is filled with the new value. SUBST-IF-NOT is the same except the values where the test returns NIL are replaced. NSUBST , NSUBST-IF , and NSUBST-IF-NOT are the recycling versions of the SUBST functions. As with most other recycling functions, you should use these functions only as drop-in replacements for their nondestructive counterparts in situations where you know there's no danger of modifying a shared structure. In particular, you must continue to save the return value of these functions since you have no guarantee that the result will be EQ to the original tree. [146] It may seem that the NSUBST family of functions can and in fact does modify the tree in place. However, there's one edge case: when the "tree" passed is, in fact, an atom, it can't be modified in place, so the result of NSUBST will be a different object than the argument: (nsubst 'x 'y 'y) X .

Sets

Sets can also be implemented in terms of cons cells. In fact, you can treat any list as a set—Common Lisp provides several functions for performing set-theoretic operations on lists. However, you should bear in mind that because of the way lists are structured, these operations get less and less efficient the bigger the sets get.

That said, using the built-in set functions makes it easy to write set-manipulation code. And for small sets they may well be more efficient than the alternatives. If profiling shows you that these functions are a performance bottleneck in your code, you can always replace the lists with sets built on top of hash tables or bit vectors.

To build up a set, you can use the function ADJOIN . ADJOIN takes an item and a list representing a set and returns a list representing the set containing the item and all the items in the original set. To determine whether the item is present, it must scan the list; if the item isn't found, ADJOIN creates a new cons cell holding the item and pointing to the original list and returns it. Otherwise, it returns the original list.

ADJOIN also takes :keyand :testkeyword arguments, which are used when determining whether the item is present in the original list. Like CONS , ADJOIN has no effect on the original list—if you want to modify a particular list, you need to assign the value returned by ADJOIN to the place where the list came from. The modify macro PUSHNEW does this for you automatically.

CL-USER> (defparameter *set* ())

*SET*

CL-USER> (adjoin 1 *set*)

(1)

CL-USER> *set*

NIL

CL-USER> (setf *set* (adjoin 1 *set*))

(1)

CL-USER> (pushnew 2 *set*)

(2 1)

CL-USER> *set*

(2 1)

CL-USER> (pushnew 2 *set*)

(2 1)

You can test whether a given item is in a set with MEMBER and the related functions MEMBER-IF and MEMBER-IF-NOT . These functions are similar to the sequence functions FIND , FIND-IF , and FIND-IF-NOT except they can be used only with lists. And instead of returning the item when it's present, they return the cons cell containing the item—in other words, the sublist starting with the desired item. When the desired item isn't present in the list, all three functions return NIL .

The remaining set-theoretic functions provide bulk operations: INTERSECTION , UNION , SET-DIFFERENCE , and SET-EXCLUSIVE-OR . Each of these functions takes two lists and :keyand :testkeyword arguments and returns a new list representing the set resulting from performing the appropriate set-theoretic operation on the two lists: INTERSECTION returns a list containing all the elements found in both arguments. UNION returns a list containing one instance of each unique element from the two arguments. [147] UNION takes only one element from each list, but if either list contains duplicate elements, the result may also contain duplicates.

SET-DIFFERENCE returns a list containing all the elements from the first argument that don't appear in the second argument. And SET-EXCLUSIVE-OR returns a list containing those elements appearing in only one or the other of the two argument lists but not in both. Each of these functions also has a recycling counterpart whose name is the same except with an N prefix.

Finally, the function SUBSETP takes two lists and the usual :keyand :testkeyword arguments and returns true if the first list is a subset of the second—if every element in the first list is also present in the second list. The order of the elements in the lists doesn't matter.

CL-USER> (subsetp '(3 2 1) '(1 2 3 4))

T

CL-USER> (subsetp '(1 2 3 4) '(3 2 1))

NIL

Lookup Tables: Alists and Plists

In addition to trees and sets, you can build tables that map keys to values out of cons cells. Two flavors of cons-based lookup tables are commonly used, both of which I've mentioned in passing in previous chapters. They're association lists , also called alists , and property lists , also known as plists . While you wouldn't use either alists or plists for large tables—for that you'd use a hash table—it's worth knowing how to work with them both because for small tables they can be more efficient than hash tables and because they have some useful properties of their own.

An alist is a data structure that maps keys to values and also supports reverse lookups, finding the key when given a value. Alists also support adding key/value mappings that shadow existing mappings in such a way that the shadowing mapping can later be removed and the original mappings exposed again.

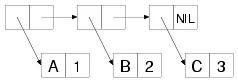

Under the covers, an alist is essentially a list whose elements are themselves cons cells. Each element can be thought of as a key/value pair with the key in the cons cell's CAR and the value in the CDR . For instance, the following is a box-and-arrow diagram of an alist mapping the symbol Ato the number 1, Bto 2, and Cto 3:

Unless the value in the CDR is a list, cons cells representing the key/value pairs will be dotted pairs in s-expression notation. The alist diagramed in the previous figure, for instance, is printed like this:

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Practical Common Lisp»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Practical Common Lisp» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Practical Common Lisp» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.