Peter Siebel - Practical Common Lisp

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Siebel - Practical Common Lisp» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2005, ISBN: 2005, Издательство: Apress, Жанр: Программирование, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Practical Common Lisp

- Автор:

- Издательство:Apress

- Жанр:

- Год:2005

- ISBN:1-59059-239-5

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Practical Common Lisp: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Practical Common Lisp»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Practical Common Lisp — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Practical Common Lisp», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In general, APPEND must copy all but its last argument, but it can always return a result that shares structure with the last argument.

Other functions take similar advantage of lists' ability to share structure. Some, like APPEND , are specified to always return results that share structure in a particular way. Others are simply allowed to return shared structure at the discretion of the implementation.

"Destructive" Operations

If Common Lisp were a purely functional language, that would be the end of the story. However, because it's possible to modify a cons cell after it has been created by SETF ing its CAR or CDR , you need to think a bit about how side effects and structure sharing mix.

Because of Lisp's functional heritage, operations that modify existing objects are called destructive— in functional programming, changing an object's state "destroys" it since it no longer represents the same value. However, using the same term to describe all state-modifying operations leads to a certain amount of confusion since there are two very different kinds of destructive operations, for-side-effect operations and recycling operations. [135] The phrase for-side-effect is used in the language standard, but recycling is my own invention; most Lisp literature simply uses the term destructive for both kinds of operations, leading to the confusion I'm trying to dispel.

For-side-effect operations are those used specifically for their side effects. All uses of SETF are destructive in this sense, as are functions that use SETF under the covers to change the state of an existing object such as VECTOR-PUSH or VECTOR-POP . But it's a bit unfair to describe these operations as destructive—they're not intended to be used in code written in a functional style, so they shouldn't be described using functional terminology. However, if you mix nonfunctional, for-side-effect operations with functions that return structure-sharing results, then you need to be careful not to inadvertently modify the shared structure. For instance, consider these three definitions:

(defparameter *list-1* (list 1 2))

(defparameter *list-2* (list 3 4))

(defparameter *list-3* (append *list-1* *list-2*))

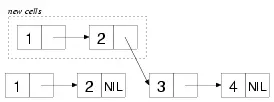

After evaluating these forms, you have three lists, but *list-3*and *list-2*share structure just like the lists in the previous diagram.

*list-1* ==> (1 2)

*list-2* ==> (3 4)

*list-3* ==> (1 2 3 4)

Now consider what happens when you modify *list-2*.

(setf (first *list-2*) 0) ==> 0

*list-2* ==> (0 4) ; as expected

*list-3* ==> (1 2 0 4) ; maybe not what you wanted

The change to *list-2*also changes *list-3*because of the shared structure: the first cons cell in *list-2*is also the third cons cell in *list-3*. SETF ing the FIRST of *list-2*changes the value in the CAR of that cons cell, affecting both lists.

On the other hand, the other kind of destructive operations, recycling operations, are intended to be used in functional code. They use side effects only as an optimization. In particular, they reuse certain cons cells from their arguments when building their result. However, unlike functions such as APPEND that reuse cons cells by including them, unmodified, in the list they return, recycling functions reuse cons cells as raw material, modifying the CAR and CDR as necessary to build the desired result. Thus, recycling functions can be used safely only when the original lists aren't going to be needed after the call to the recycling function.

To see how a recycling function works, let's compare REVERSE , the nondestructive function that returns a reversed version of a sequence, to NREVERSE , a recycling version of the same function. Because REVERSE doesn't modify its argument, it must allocate a new cons cell for each element in the list being reversed. But suppose you write something like this:

(setf *list* (reverse *list*))

By assigning the result of REVERSE back to *list*, you've removed the reference to the original value of *list*. Assuming the cons cells in the original list aren't referenced anywhere else, they're now eligible to be garbage collected. However, in many Lisp implementations it'd be more efficient to immediately reuse the existing cons cells rather than allocating new ones and letting the old ones become garbage.

NREVERSE allows you to do exactly that. The N stands for non-consing , meaning it doesn't need to allocate any new cons cells. The exact side effects of NREVERSE are intentionally not specified—it's allowed to modify any CAR or CDR of any cons cell in the list—but a typical implementation might walk down the list changing the CDR of each cons cell to point to the previous cons cell, eventually returning the cons cell that was previously the last cons cell in the old list and is now the head of the reversed list. No new cons cells need to be allocated, and no garbage is created.

Most recycling functions, like NREVERSE , have nondestructive counterparts that compute the same result. In general, the recycling functions have names that are the same as their non-destructive counterparts except with a leading N . However, not all do, including several of the more commonly used recycling functions such as NCONC , the recycling version of APPEND , and DELETE , DELETE-IF , DELETE-IF-NOT , and DELETE-DUPLICATES , the recycling versions of the REMOVE family of sequence functions.

In general, you use recycling functions in the same way you use their nondestructive counterparts except it's safe to use them only when you know the arguments aren't going to be used after the function returns. The side effects of most recycling functions aren't specified tightly enough to be relied upon.

However, the waters are further muddied by a handful of recycling functions with specified side effects that can be relied upon. They are NCONC , the recycling version of APPEND , and NSUBSTITUTE and its -IFand -IF-NOTvariants, the recycling versions of the sequence functions SUBSTITUTE and friends.

Like APPEND , NCONC returns a concatenation of its list arguments, but it builds its result in the following way: for each nonempty list it's passed, NCONC sets the CDR of the list's last cons cell to point to the first cons cell of the next nonempty list. It then returns the first list, which is now the head of the spliced-together result. Thus:

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Practical Common Lisp»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Practical Common Lisp» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Practical Common Lisp» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.