Peter Siebel - Practical Common Lisp

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Siebel - Practical Common Lisp» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2005, ISBN: 2005, Издательство: Apress, Жанр: Программирование, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Practical Common Lisp

- Автор:

- Издательство:Apress

- Жанр:

- Год:2005

- ISBN:1-59059-239-5

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Practical Common Lisp: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Practical Common Lisp»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Practical Common Lisp — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Practical Common Lisp», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

So when I say a particular value is a list, what I really mean is it's either NIL or a reference to a cons cell. The CAR of the cons cell is the first item of the list, and the CDR is a reference to another list, that is, another cons cell or NIL , containing the remaining elements. The Lisp printer understands this convention and prints such chains of cons cells as parenthesized lists rather than as dotted pairs.

(cons 1 nil) ==> (1)

(cons 1 (cons 2 nil)) ==> (1 2)

(cons 1 (cons 2 (cons 3 nil))) ==> (1 2 3)

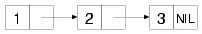

When talking about structures built out of cons cells, a few diagrams can be a big help. Box-and-arrow diagrams represent cons cells as a pair of boxes like this:

The box on the left represents the CAR , and the box on the right is the CDR . The values stored in a particular cons cell are either drawn in the appropriate box or represented by an arrow from the box to a representation of the referenced value. [134] Typically, simple objects such as numbers are drawn within the appropriate box, and more complex objects will be drawn outside the box with an arrow from the box indicating the reference. This actually corresponds well with how many Common Lisp implementations work—although all objects are conceptually stored by reference, certain simple immutable objects can be stored directly in a cons cell.

For instance, the list (1 2 3), which consists of three cons cells linked together by their CDR s, would be diagrammed like this:

However, most of the time you work with lists you won't have to deal with individual cons cells—the functions that create and manipulate lists take care of that for you. For example, the LIST function builds a cons cells under the covers for you and links them together; the following LIST expressions are equivalent to the previous CONS expressions:

(list 1) ==> (1)

(list 1 2) ==> (1 2)

(list 1 2 3) ==> (1 2 3)

Similarly, when you're thinking in terms of lists, you don't have to use the meaningless names CAR and CDR ; FIRST and REST are synonyms for CAR and CDR that you should use when you're dealing with cons cells as lists.

(defparameter *list* (list 1 2 3 4))

(first *list*) ==> 1

(rest *list*) ==> (2 3 4)

(first (rest *list*)) ==> 2

Because cons cells can hold any kind of values, so can lists. And a single list can hold objects of different types.

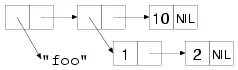

(list "foo" (list 1 2) 10) ==> ("foo" (1 2) 10)

The structure of that list would look like this:

Because lists can have other lists as elements, you can also use them to represent trees of arbitrary depth and complexity. As such, they make excellent representations for any heterogeneous, hierarchical data. Lisp-based XML processors, for instance, usually represent XML documents internally as lists. Another obvious example of tree-structured data is Lisp code itself. In Chapters 30 and 31 you'll write an HTML generation library that uses lists of lists to represent the HTML to be generated. I'll talk more next chapter about using cons cells to represent other data structures.

Common Lisp provides quite a large library of functions for manipulating lists. In the sections "List-Manipulation Functions" and "Mapping," you'll look at some of the more important of these functions. However, they will be easier to understand in the context of a few ideas borrowed from functional programming.

Functional Programming and Lists

The essence of functional programming is that programs are built entirely of functions with no side effects that compute their results based solely on the values of their arguments. The advantage of the functional style is that it makes programs easier to understand. Eliminating side effects eliminates almost all possibilities for action at a distance. And since the result of a function is determined only by the values of its arguments, its behavior is easier to understand and test. For instance, when you see an expression such as (+ 3 4), you know the result is uniquely determined by the definition of the + function and the values 3and 4. You don't have to worry about what may have happened earlier in the execution of the program since there's nothing that can change the result of evaluating that expression.

Functions that deal with numbers are naturally functional since numbers are immutable. A list, on the other hand, can be mutated, as you've just seen, by SETF ing the CAR s and CDR s of the cons cells that make up its backbone. However, lists can be treated as a functional data type if you consider their value to be determined by the elements they contain. Thus, any list of the form (1 2 3 4)is functionally equivalent to any other list containing those four values, regardless of what cons cells are actually used to represent the list. And any function that takes a list as an argument and returns a value based solely on the contents of the list can likewise be considered functional. For instance, the REVERSE sequence function, given the list (1 2 3 4), always returns a list (4 3 2 1). Different calls to REVERSE with functionally equivalent lists as the argument will return functionally equivalent result lists. Another aspect of functional programming, which I'll discuss in the section "Mapping," is the use of higher-order functions: functions that treat other functions as data, taking them as arguments or returning them as results.

Most of Common Lisp's list-manipulation functions are written in a functional style. I'll discuss later how to mix functional and other coding styles, but first you should understand a few subtleties of the functional style as applied to lists.

The reason most list functions are written functionally is it allows them to return results that share cons cells with their arguments. To take a concrete example, the function APPEND takes any number of list arguments and returns a new list containing the elements of all its arguments. For instance:

(append (list 1 2) (list 3 4)) ==> (1 2 3 4)

From a functional point of view, APPEND 's job is to return the list (1 2 3 4)without modifying any of the cons cells in the lists (1 2)and (3 4). One obvious way to achieve that goal is to create a completely new list consisting of four new cons cells. However, that's more work than is necessary. Instead, APPEND actually makes only two new cons cells to hold the values 1and 2, linking them together and pointing the CDR of the second cons cell at the head of the last argument, the list (3 4). It then returns the cons cell containing the 1. None of the original cons cells has been modified, and the result is indeed the list (1 2 3 4). The only wrinkle is that the list returned by APPEND shares some cons cells with the list (3 4). The resulting structure looks like this:

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Practical Common Lisp»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Practical Common Lisp» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Practical Common Lisp» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.