Since this single widget is the only content in our activity, we only need this single element. Complex UIs will require a whole tree of elements, representing the widgets and containers that control their positioning. All the remaining chapters of this book will use the XML layout form whenever practical, so there are dozens of other examples of more complex layouts for you to peruse from Chapter 7 onward.

Many widgets and containers only need to appear in the XML layout file and do not need to be referenced in your Java code. For example, a static label ( TextView) frequently only needs to be in the layout file to indicate where it should appear. These sorts of elements in the XML file do not need to have the android:idattribute to give them a name.

Anything you do want to use in your Java source, though, needs an android:id.

The convention is to use @+id/...as the id value, where the ...represents your locally-unique name for the widget in question. In the XML layout example in the preceding section, @+id/buttonis the identifier for the Buttonwidget.

Android provides a few special android:idvalues, of the form @android:id/.... We will see some of these in various chapters of this book, such as Chapters 8 and 10.

We Attach These to the Java… How?

Given that you have painstakingly set up the widgets and containers in an XML layout file named main.xmlstored in res/layout, all you need is one statement in your activity’s onCreate()callback to use that layout:

setContentView(R.layout.main);

This is the same setContentView()we used earlier, passing it an instance of a Viewsubclass (in that case, a Button). The Android-built view, constructed from our layout, is accessed from that code-generated Rclass. All of the layouts are accessible under R.layout, keyed by the base name of the layout file — main.xmlresults in R.layout.main.

To access our identified widgets, use findViewById(), passing in the numeric identifier of the widget in question. That numeric identifier was generated by Android in the Rclass as R.id.something(where something is the specific widget you are seeking). Those widgets are simply subclasses of View, just like the Buttoninstance we created in Chapter 4.

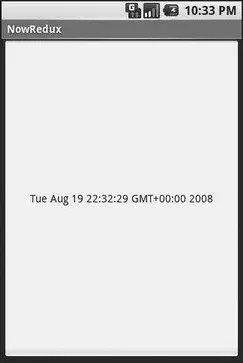

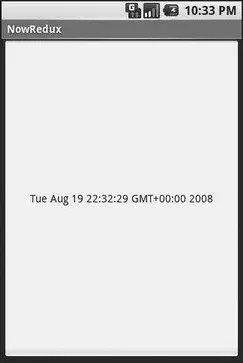

In the original Nowdemo, the button’s face would show the current time, which would reflect when the button was last pushed (or when the activity was first shown, if the button had not yet been pushed).

Most of that logic still works, even in this revised demo ( NowRedux). However, rather than instantiating the Button in our activity’s onCreate()callback, we can reference the one from the XML layout:

packagecom.commonsware.android.layouts;

importandroid.app.Activity;

importandroid.os.Bundle;

importandroid.view.View;

importandroid.widget.Button;

importjava.util.Date;

public classNowRedux extendsActivity

implementsView.OnClickListener {

Button btn;

@Override

publicvoid onCreate(Bundle icicle) {

super. onCreate(icicle);

setContentView(R.layout.main);

btn=(Button) findViewById(R.id.button);

btn. setOnClickListener( this);

updateTime();

}

publicvoid onClick(View view) {

updateTime();

}

privatevoid updateTime() {

btn. setText( new Date(). toString());

}

}

The first difference is that rather than setting the content view to be a view we created in Java code, we set it to reference the XML layout ( setContentView(R.layout.main)). The R.javasource file will be updated when we rebuild this project to include a reference to our layout file (stored as main.xmlin our project’s res/layoutdirectory).

The other difference is that we need to get our hands on our Buttoninstance, for which we use the findViewById()call. Since we identified our button as @+id/button, we can reference the button’s identifier as R.id.button. Now, with the Buttoninstance in hand, we can set the callback and set the label as needed.

As you can see in Figure 5-1, the results look the same as with the original Nowdemo.

Figure 5-1. The NowRedux sample activity

CHAPTER 6

Employing Basic Widgets

Every GUI toolkit has some basic widgets: fields, labels, buttons, etc. Android’s toolkit is no different in scope, and the basic widgets will provide a good introduction as to how widgets work in Android activities.

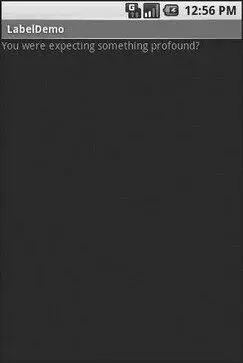

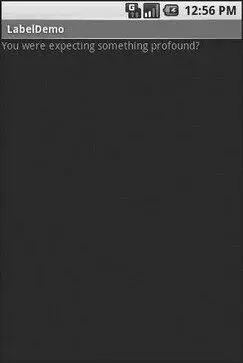

The simplest widget is the label, referred to in Android as a TextView. Like in most GUI toolkits, labels are bits of text not editable directly by users. Typically, they are used to identify adjacent widgets (e.g., a “Name:” label before a field where one fills in a name).

In Java, you can create a label by creating a TextViewinstance. More commonly, though, you will create labels in XML layout files by adding a TextViewelement to the layout, with an android:textproperty to set the value of the label itself. If you need to swap labels based on certain criteria, such as internationalization, you may wish to use a resource reference in the XML instead, as will be described in Chapter 9. TextViewhas numerous other properties of relevance for labels, such as:

• android:typefaceto set the typeface to use for the label (e.g., monospace)

• android:textStyleto indicate that the typeface should be made bold ( bold), italic ( italic), or bold and italic ( bold_italic)

• android:textColorto set the color of the label’s text, in RGB hex format (e.g., #FF0000for red)

For example, in the Basic/Label project, you will find the following layout file:

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:text="You were expecting something profound?"

/>

As you can see in Figure 6-1, just that layout alone, with the stub Java source provided by Android’s project builder (e.g., activityCreator), gives you the application.

Figure 6-1. The LabelDemo sample application

Читать дальше