android.R.layout.simple_list_item_1, items));

}

publicvoid onListItemClick(ListView parent, View v, int position,

long id) {

selection. setText(items. get(position). toString());

}

}

Now, inside our try...catchblock, we get our XmlPullParserand loop until the end of the document. If the current event is START_TAGand the name of the element is word xpp.getName().equals("word")), then we get the one-and-only attribute and pop that into our list of items for the selection widget. Since we’re in complete control over the XML file, it is safe enough to assume there is exactly one attribute. But, if you were not as comfortable that the XML is properly defined, you might consider checking the attribute count (getAttributeCount())and the name of the attribute ( getAttributeName()) before blindly assuming the 0-index attribute is what you think it is.

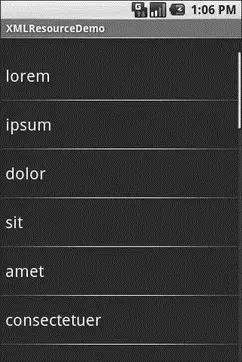

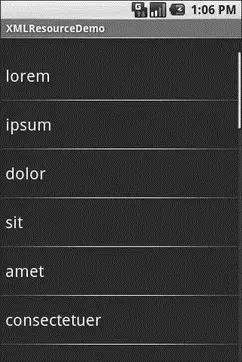

As you can see in Figure 19-4, the result looks the same as before, albeit with a different name in the title bar.

Figure 19-4. The XMLResourceDemo sample application

In the res/values/directory, you can place one (or more) XML files describing simple resources: dimensions, colors, and arrays. We have already seen uses of dimensions and colors in previous examples, where they were passed as simple strings (e.g., "10px") as parameters to calls. You can, of course, set these up as Java static final objects and use their symbolic names… but this only works inside Java source, not in layout XML files. By putting these values in resource XML files, you can reference them from both Java and layouts, plus have them centrally located for easy editing.

Resource XML files have a root element of resources; everything else is a child of that root.

Dimensions are used in several places in Android to describe distances, such as a widget’s padding. While this book usually uses pixels (e.g., 10pxfor ten pixels), there are several different units of measurement available to you:

• inand mmfor inches and millimeters, respectively, based on the actual size of the screen

• ptfor points, which in publishing terms is 1/72nd of an inch (again, based on the actual physical size of the screen)

• dpand spfor device-independent pixels and scale-independent pixels — one pixel equals one dp for a 160dpi resolution screen, with the ratio scaling based on the actual screen pixel density (scale-independent pixels also take into account the user’s preferred font size)

To encode a dimension as a resource, add a dimenelement, with a name attribute for your unique name for this resource, and a single child text element representing the value:

10px

1in

In a layout, you can reference dimensions as @dimen/..., where the ellipsis is a placeholder for your unique name for the resource (e.g., thin and fat from the previous sample). In Java, you reference dimension resources by the unique name prefixed with R.dimen.(e.g., Resources.getDimen(R.dimen.thin)).

Colors in Android are hexadecimal RGB values, also optionally specifying an alpha channel.

You have your choice of single-character hex values or double-character hex values, leaving you with four styles:

• #RGB

• #ARGB

• #RRGGBB

• #AARRGGBB

These work similarly to their counterparts in Cascading Style Sheets (CSS).

You can, of course, put these RGB values as string literals in Java source or layout resources. If you wish to turn them into resources, though, all you need to do is add color elements to the resources file, with a name attribute for your unique name for this color, and a single text element containing the RGB value itself:

#FFD555

#005500

#8A3324

In a layout, you can reference colors as @color/..., replacing the ellipsis with your unique name for the color (e.g., burnt_umber). In Java, you reference color resources by the unique name prefixed with R.color.(e.g., Resources.getColor(R.color.forest_green)).

Array resources are designed to hold lists of simple strings, such as a list of honorifics (Mr., Mrs., Ms., Dr., etc.).

In the resource file, you need one string-array element per array, with a name attribute for the unique name you are giving the array. Then, add one or more child item elements, each of which have a single text element with the value for that entry in the array:

Philadelphia

Pittsburgh

Allentown/Bethlehem

Erie

Reading

Scranton

Lancaster

Altoona

Harrisburg

PHL

PIT

ABE

ERI

RDG

AVP

LNS

AOO

MDT

From your Java code, you can then use Resources.getStringArray()to get a String[]of the items in the list. The parameter to getStringArray()is your unique name for the array, prefixed with R.array.(e.g., Resources.getStringArray(R.array.honorifics)).

Different Strokes for Different Folks

One set of resources may not fit all situations where your application may be used. One obvious area comes with string resources and dealing with internationalization (I18N) and localization (L10N). Putting strings all in one language works fine — probably at least for the developer — but only covers one language.

That is not the only scenario where resources might need to differ, though. Here are others:

• Screen orientation: is the screen in a portrait orientation? Landscape? Is the screen square and, therefore, does not really have an orientation?

• Screen size: how many pixels does the screen have, so you can size your resources accordingly (e.g., large versus small icons)?

• Touchscreen: does the device have a touchscreen? If so, is the touchscreen set up to be used with a stylus or a finger?

• Keyboard: what keyboard does the user have (QWERTY, numeric, neither), either now or as an option?

• Other input: does the device have some other form of input, like a directional pad or click-wheel?

The way Android currently handles this is by having multiple resource directories, with the criteria for each embedded in their names.

Suppose, for example, you want to support strings in both English and Spanish. Normally, for a single-language setup, you would put your strings in a file named res/values/strings.xml. To support both English and Spanish, you would create two folders, res/values-enand res/values-es, where the value after the hyphen is the ISO 639-1 [18] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ISO_639-1

two-letter code for the language you want. Your English-language strings would go in res/values-en/strings.xmland the Spanish ones in res/values-es/strings.xml. Android will choose the proper file based on the user’s device settings.

Читать дальше