The Kind of Pop-Ups You Like

Of course, not all preferences are checkboxes and ringtones.

For others, like entry fields and lists, Android uses pop-up dialogs. Users do not enter their preference directly in the preference UI activity, but rather tap on a preference, fill in a value, and click OK to commit the change.

Structurally, in the preference XML, fields and lists are not significantly different from other preference types, as seen in this preference XML from the Prefs/Dialogssample project available at http://apress.com:

xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android">

android:key="@string/checkbox"

android:title="Checkbox Preference"

android:summary="Check it on, check it off"

/>

android:key="@string/ringtone"

android:title="Ringtone Preference"

android:showDefault="true"

android:showSilent="true"

android:summary="Pick a tone, any tone"

/>

android:key="detail"

android:title="Detail Screen"

android:summary="Additional preferences held in another page">

android:key="@string/checkbox2"

android:title="Another Checkbox"

android:summary="On. Off. It really doesn't matter."

/>

android:key="@string/text"

android:title="Text Entry Dialog"

android:summary="Click to pop up a field for entry"

android:dialogTitle="Enter something useful"

/>

android:key="@string/list"

android:title="Selection Dialog"

android:summary="Click to pop up a list to choose from"

android:entries="@array/cities"

android:entryValues="@array/airport_codes"

android:dialogTitle="Choose a Pennsylvania city" />

With the field ( EditTextPreference), in addition to the title and summary you put on the preference itself, you can also supply the title to use for the dialog.

With the list ( ListPreference), you supply both a dialog title and two string-array resources: one for the display names, one for the values. These need to be in the same order — the index of the chosen display name determines which value is stored as the preference in the SharedPreferences. For example, here are the arrays for use by the ListPreferenceshown previously:

Philadelphia

Pittsburgh

Allentown/Bethlehem

Erie

Reading

Scranton

Lancaster

Altoona

Harrisburg

PHL

PIT

ABE

ERI

RDG

AVP

LNS

AOO

MDT

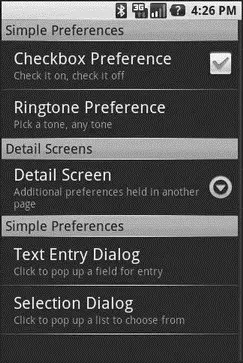

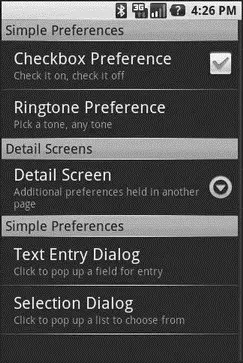

When you bring up the preference UI, you start with another category with another pair of preference entries (see Figure 17-6).

Figure 17-6. The preference screen of the Dialogs project’s preference UI

Tapping the Text Entry Dialog preference brings up… a text-entry dialog — in this case, with the prior preference entry pre–filled in (Figure 17-7).

Figure 17-7. Editing a text preference

Tapping the Selection Dialog preference brings up… a selection dialog, showing the display names (Figure 17-8).

Figure 17-8. Editing a list preference

CHAPTER 18

Accessing Files

While Android offers structured storage, via preferences and databases, sometimes a simple file will suffice. Android offers two models for accessing files: one for files pre-packaged with your application, and one for files created on-device by your application.

You and the Horse You Rode in On

Let’s suppose you have some static data you want to ship with the application, such as a list of words for a spell-checker. The easiest way to deploy that is to put the file in the res/raw directory, so it gets put in the Android application APK file as part of the packaging process as a raw resource.

To access this file, you need a Resourcesobject. From an activity, that is as simple as calling getResources(). A Resourcesobject offers openRawResource()to get an InputStreamon the file you specify. Rather than a path, openRawResource()expects an integer identifier for the file as packaged. This works just like accessing widgets via findViewById()— if you put a file named words.xmlin res/raw, the identifier is accessible in Java as R.raw.words.

Since you can get only an InputStream, you have no means of modifying this file. Hence, it is really useful only for static reference data. Moreover, since it is unchanging until the user installs an updated version of your application package, either the reference data has to be valid for the foreseeable future, or you need to provide some means of updating the data. The simplest way to handle that is to use the reference data to bootstrap some other modifiable form of storage (e.g., a database), but this makes for two copies of the data in storage. An alternative is to keep the reference data as is but keep modifications in a file or database, and merge them together when you need a complete picture of the information. For example, if your application ships a file of URLs, you could have a second file that tracks URLs added by the user or reference URLs that were deleted by the user.

In the Files/Staticsample project available in the Source Code section of http://apress.com, you will find a reworking of the listbox example from Chapter 8, this time using a static XML file instead of a hard-wired array in Java. The layout is the same:

android:orientation="vertical"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="fill_parent" >

android:id="@+id/selection"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

/>

android:id="@android:id/list"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="fill_parent"

android:drawSelectorOnTop="false"

/>

In addition to that XML file, you need an XML file with the words to show in the list:

While this XML structure is not exactly a model of space efficiency, it will suffice for a demo.

The Java code now must read in that XML file, parse out the words, and put them someplace for the list to pick up:

public classStaticFileDemo extendsListActivity {

TextView selection;

Читать дальше