There are a few widgets and containers you need to use in order to set up a tabbed portion of a view:

• TabHostis the overarching container for the tab buttons and tab contents.

• TabWidgetimplements the row of tab buttons, which contain text labels and optionally contain icons.

• FrameLayoutis the container for the tab contents; each tab content is a child of the FrameLayout.

This is similar to the approach that Mozilla’s XUL takes. In XUL’s case, the tabboxelement corresponds to Android’s TabHost, the tabs element corresponds to TabWdget, and tabpanelscorresponds to the FrameLayout.

There are a few rules to follow, at least in this milestone edition of the Android toolkit, in order to make these three work together:

• You mus t give the TabWidgetan android:idof @android:id/tabs.

• You must set aside some padding in the FrameLayoutfor the tab buttons.

• If you wish to use the TabActivity, you must give the TabHostan android:idof @android:id/tabhost.

TabActivity, like ListActivity, wraps a common UI pattern (activity made up entirely of tabs) into a pattern-aware activity subclass. You do not necessarily have to use TabActivity— a plain activity can use tabs as well.

With respect to the FrameLayoutpadding issue, for whatever reason, the TabWidgetdoes not seem to allocate its own space inside the TabHostcontainer. In other words, no matter what you specify for android:layout_height for the TabWidget, the FrameLayoutignores it and draws at the top of the overall TabHost. Your tab contents obscure your tab buttons. Hence, you need to leave enough padding (via android:paddingTop) in FrameLayoutto “shove” the actual tab contents down beneath the tab buttons.

In addition, the TabWidgetseems to always draw itself with room for icons, even if you do not supply icons. Hence, for this version of the toolkit, you need to supply at least 62 pixels of padding, perhaps more depending on the icons you supply.

For example, here is a layout definition for a tabbed activity, from Fancy/Tab:

android:orientation="vertical"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="fill_parent">

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="fill_parent">

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

/>

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="fill_parent"

android:paddingTop="62px">

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="fill_parent"

android:layout_centerHorizontal="true"

/>

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="fill_parent"

android:text="A semi-random button"

/>

Note that the TabWidgetand FrameLayoutare immediate children of the TabHost, and the FrameLayoutitself has children representing the various tabs. In this case, there are two tabs: a clock and a button. In a more complicated scenario, the tabs are probably some form of container (e.g., LinearLayout) with their own contents.

The Java code needs to tell the TabHostwhat views represent the tab contents and what the tab buttons should look like. This is all wrapped up in TabSpecobjects. You get a TabSpecinstance from the host via newTabSpec(), fill it out, then add it to the host in the proper sequence.

The two key methods on TabSpecare:

• setContent(), where you indicate what goes in the tab content for this tab, typically the android:idof the view you want shown when this tab is selected

• setIndicator(), where you provide the caption for the tab button and, in some flavors of this method, supply a Drawableto represent the icon for the tab

Note that tab “indicators” can actually be views in their own right, if you need more control than a simple label and optional icon.

Also note that you must call setup()on the TabHostbefore configuring any of these TabSpecobjects. The call to setup()is not needed if you are using the TabActivitybase class for your activity.

For example, here is the Java code to wire together the tabs from the preceding layout example:

packagecom.commonsware.android.fancy;

importandroid.app.Activity;

importandroid.os.Bundle;

importandroid.widget.TabHost;

public classTabDemo extendsActivity {

@Override

publicvoid onCreate(Bundle icicle) {

super. onCreate(icicle);

setContentView(R.layout.main);

TabHost tabs = (TabHost) findViewById(R.id.tabhost);

tabs. setup();

TabHost.TabSpec spec = tabs. newTabSpec(tag1);

spec. setContent(R.id.tab1);

spec. setIndicator(Clock);

tabs. addTab(spec);

spec = tabs. newTabSpec(tag2);

spec. setContent(R.id.tab2);

spec. setIndicator(Button);

tabs. addTab(spec);

tabs. setCurrentTab(0);

}

}

We find our TabHostvia the familiar findViewById()method, then have it call setup(). After that, we get a TabSpecvia newTabSpec(), supplying a tag whose purpose is unknown at this time. Given the spec, you call setContent()and setIndicator(), then call addTab()back on the TabHostto register the tab as available for use. Finally, you can choose which tab is the one to show via setCurrentTab(), providing the 0-based index of the tab.

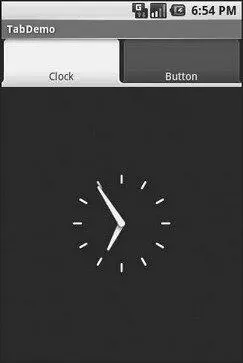

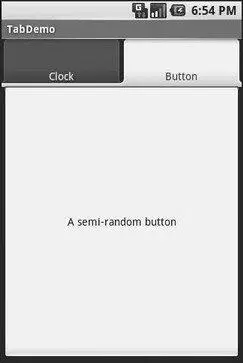

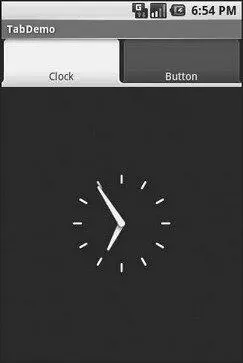

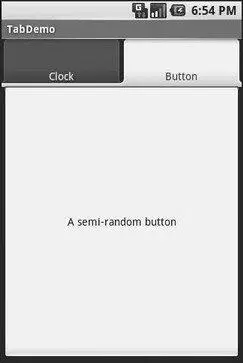

The results can be seen in Figures 10-5 and 10-6.

Figure 10-5. The TabDemo sample application, showing the first tab

Figure 10-6. The same application, showing the second tab

TabWidgetis set up to allow you to easily define tabs at compile time. However, sometimes, you want to add tabs to your activity during runtime. For example, imagine an email client where individual emails get opened in their own tab for easy toggling between messages. In this case, you don’t know how many tabs or what their contents will be until runtime, when the user chooses to open a message.

Читать дальше