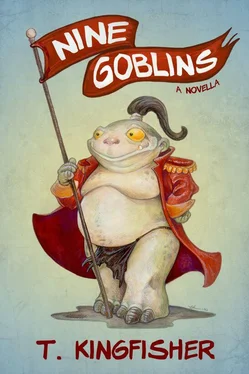

T. Kingfisher - Nine Goblins

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «T. Kingfisher - Nine Goblins» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, ISBN: 2013, Издательство: Smashwords Edition, Жанр: Юмористическая фантастика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nine Goblins

- Автор:

- Издательство:Smashwords Edition

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:9781310505768

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nine Goblins: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nine Goblins»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nine Goblins is a novella of low...very low...fantasy.

Nine Goblins — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nine Goblins», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

T. Kingfisher

Nine Goblins

For Kevin, who had to put up with this story for a very long time.

ONE

It was gruel again for breakfast.

It had been gruel for dinner the night before, and it would be gruel sandwiches for lunch, a dish only possible with goblin gruel, which was burnt solid and could be trusted not to ooze off the bread. It usually had unidentifiable lumps of something in it. Sometimes the lumps had legs.

Once, Corporal Algol had found an eyeball in his gruel, the memory of which he carried with him like a good luck charm and inflicted regularly on his fellow soldiers.

“Did I ever tell you guys about the time I found an eyeball—”

“Yes.”

“Oh.”

Algol wasn’t a bad sort, really. He was bigger than usual for a goblin, a whopping four foot ten, with broad, knotty shoulders and enormous feet. He had the ochre-grey skin of a hill goblin, and he wasn’t all that bright—but then, he was a goblin officer.

Smart goblins became mechanics. Dumb goblins became soldiers. Really dumb goblins became officers.

One of the latter was gesturing grandly from the top of a nearby rise. Nobody in the Nineteenth Infantry (better known as the Whinin’ Niners) could hear what he was saying, but this was probably a good thing. If you couldn’t hear what the officers said, you couldn’t be said to be disobeying orders. It was amazing how selectively deaf goblin soldiers could be, particularly when words like “Charge!” and “Advance!” and “Get your finger out of there, soldier!” were involved.

“What do you think he’s on about?” asked Weatherby, jerking his thumb in the direction of the officer.

Everybody turned and looked, since there was nothing else to do. They had been sitting in the middle of a stony wasteland for a week, and it was either watch the officers or watch the bird. (There was only the one bird, and it had been hanging around waiting for something to die for most of that week.)

The officer was waving his arms wildly now and hopping on one foot, like a man being attacked by ants. His red coat flapped in the breeze like shabby scarlet wings.

“We’re going to move out,” said Murray.

“You think?”

Murray nodded. “He’s making a big speech. He only does that when he thinks we might get into a scrape with the enemy. The enemy’s not gonna come at us here, so we must be moving out.”

For a goblin, Murray was a genius. He’d washed out of the Mechanics Corps for being too good at his job. Goblins appreciate machines that are big and clunky and have lots of spiky bits sticking off them, and which break down and explode and take half the Corps with them. That’s how you knew it worked. If it couldn’t kill goblins, how could you trust it to kill the enemy?

Murray made small, neat, efficient devices that didn’t even maim anybody during the construction phases. Nobody believed for a minute that the things would work, and Murray was sent down to the infantry in disgrace.

When his designs later proved dramatically successful, leaving enormous craters in the enemy ranks, and on one notable occasion, causing an entire platoon of elves to simultaneously wet themselves on the field of battle, nobody could remember who’d built them. There was such a rapid turnover in the Mechanics Corps that the people who’d thrown him out were now mostly scattered in bits across the landscape, or had transferred back to Goblinhome to teach.

Murray was, therefore, the exception to the Whinin’ Nineteenth—and indeed, to most of the surviving Goblin infantry. “Too dumb to desert. Too smart to die.”

Even this was more clever than accurate. There are situations where no amount of smarts keeps you from getting killed. Blockhammer had been sitting down at breakfast a week ago, as canny a goblin veteran as you could wish for, and one of the supply rocs had gotten sweaty claws. The gigantic bird had been passing directly overhead, and the elephant it was carrying popped right out of its talons and landed directly on Blockhammer’s head. (Also on his body, his camp stool, and all the space in a fifteen foot radius around him.)

When they went to bury him, they couldn’t figure out which bits were Blockhammer and which bits were the elephant, so the Nineteeth had buried his sword instead. They rolled a stone over it, and Murray wrote “RIP- BLoKhaMer” on it (his genius did not extend to spelling.), and Nessilka had sung a goblin lament. Everyone was very moved, and toasted Blockhammer’s memory repeatedly over the next batch of elephant gruel. (It was possible the gruel also contained bits of Blockhammer. Nobody wanted to dwell on this.)

The other half of the saying wasn’t too accurate either. Weatherby, for example, had deserted no less than fifteen times, and he was so dumb it was remarkable he hadn’t been tapped as officer material.

It was really pretty easy to desert—people did it all the time—but Weatherby had made an art of it. He would nod to the rest of the Nineteenth, as they sat around the campfire, and say “Right, I’m off then!” and then walk in a straight line until he hit the edge of the Goblin Army encampment. Once he was fifty feet from the edge of camp, Weatherby proceeded to rip off his clothes, run to the nearest hill, rise or tree stump, and begin dancing wildly in the moonlight, while shouting “I’m free, you sods, free! I’m a free goblin! Waahoooo! Free!”

Eventually the guards would come get him and bring him home again, although his clothes were usually a loss.

Since the Goblin Army had blown almost all its uniform budget on red coats for the officers, everybody was wearing loincloths from home anyway, so nobody much noticed.

A runner came up to the edge of the fire where the Nineteenth were sitting. “New orders, Sergeant!” he said, saluting Nessilka.

Nessilka muttered something under her breath. She was the ranking member of the Nineteenth since Blockhammer had gotten splattered, followed by Murray and Algol, who were corporals, and everybody else, who weren’t. You could tell the ranks by the stripes on the loincloth, although this system had drawbacks if you were trying to tell the difference between a general and somebody who just didn’t do laundry often enough.

Nessilka didn’t like being in charge. She was good at it, but she didn’t like it. She had been the oldest of six children and was the veteran of three campaigns, and as a result, both responsibility and suspicion of rank were etched in Nessilka’s bones. Finding herself as the senior member of the Whinin’ Niners was like a constant itch between her shoulderblades.

“What’s the word, then?” she asked.

“General Globberlich says to break camp. We’re movin’ out!” He saluted again. He had to be new. Nobody was that enthusiastic after the first month.

“Will do,” said Nessilka, and waited.

The runner saluted again. He was a scrawny little green fellow, probably with imp blood somewhere a few generations back.

He saluted for the fourth time, hard enough to bruise his forehead.

Sergeant Nessilka took pity on him and saluted back, and he ran off to the next camp.

Nessilka was a female goblin, which meant that everybody was a little scared of her. Occasionally you saw women in the enemy armies—generally slim, willowy young women with longbows and grim expressions. She wondered if everybody on their side tiptoed around them like naughty children with an unpredictable schoolteacher.

Somehow, she doubted it.

There was nothing slim or willowy about Nessilka. She was built like a chunk of granite, and she could carry a live boar under one arm. The only concession to femininity was that she wore her hair in a bun instead of a long queue, and she wore slightly fewer earrings than everyone else.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Nine Goblins»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nine Goblins» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nine Goblins» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.