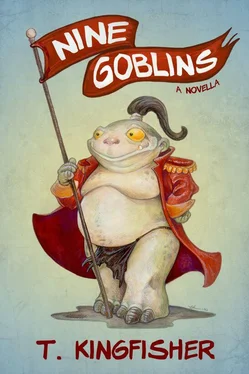

T. Kingfisher - Nine Goblins

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «T. Kingfisher - Nine Goblins» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, ISBN: 2013, Издательство: Smashwords Edition, Жанр: Юмористическая фантастика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nine Goblins

- Автор:

- Издательство:Smashwords Edition

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:9781310505768

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nine Goblins: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nine Goblins»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nine Goblins is a novella of low...very low...fantasy.

Nine Goblins — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nine Goblins», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Sings-to-Trees went around the side of the ramshackle barn, found his shovel, and went to work on the stall. It was hot work, lifting each shovelful into the wooden wheelbarrow, and he was sweating by the time he wheeled the first load up to the garden. Unicorn dung was pretty safe fertilizer. Sometimes the magical creatures had pretty unusual things in their waste. He’d once nursed an injured peryton, a great grey stag with the wings of a heron and the carnivorous diet of a lion, for two weeks. He’d gone through a lot of chickens. Afterwards, he’d put the dung on his tomato plants, and they’d grown six feet practically overnight. He could have handled that, but the fruit grew tiny green antlers. He could probably have handled that , too, even after they shed their velvet and got unsettlingly sharp, but he started finding the tomatoes gored and dripping seeds in the morning. Then the nearby zucchini began showing up with scarred rinds and suspicious gouges. Eventually he was down to one big eight-point tomato buck, a vicious vegetable he suspected was plotting to kill him. He’d put on his cockatrice-handling gloves, and torn the whole patch out before things got out of hand.

He’d left that corner empty for a year, and then put in chard. Chard seemed pretty innocuous. Not a lot of mayhem available to chard. He didn’t actually like chard, but there were plenty of animals that came through that would. So far it hadn’t done anything suspicious. He shuddered to think what would have happened with potatoes.

The second wheelbarrow load came and went, and that was it. He sluiced the stones down with water and listened to it gurgle away, feeling the satisfaction of a dirty job done well.

A hoof stamped on the stones. He turned.

There was a dead deer looking at him.

He didn’t yelp. On the scale of weird things that had come to him for help, this didn’t even make the top ten. Still, he did inhale sharply, and he was glad the shovel was within easy reach.

It was a complete skeleton, fully articulated, standing framed in the square of light of the open barn door. Its filigreed shadow streamed away into the darkness of the barn and was lost.

He knew it was a deer because of the hooves and the skull and the build, but the delicacy of the thin bone legs was belied by the great rack of antlers on its head, a massive, labyrinthine rack, more than he’d known a deer could possibly fit onto its skull.

For one horrible moment, he wondered if thinking about the peryton had summoned its ghost—but no, there were no wings, and so far as he knew, the beast was still alive. This creature was probably not alive. At least, not in the conventional sense.

It looked at him.

It didn’t have eyes, and its empty eye sockets weren’t full of eldritch fire, or even darkness. They were just eye sockets, full of ivory shadows and little more. Nevertheless, it looked at him.

“Can I help you?” he said.

It kept looking at him.

He spread his hands and took a cautious step forward, then another. It tilted its head, very slowly, and one hind hoof lifted a little, and scraped at the cobbles, the faintest sound, like a tree branch creaking in a soft breeze.

“Do you need help?” he tried again, and took another step.

It rattled at him. He froze.

The skeleton was articulated, so far as he could tell, by a kind of fine dark webbing at the joints. It looked almost like dried algae, brownish-black and forming organic loops and swirls over the balls of the joints. The deer had given a kind of rolling full-body shrug, down the length of its spine, and the clatter of vertebrae together had made the rattling noise he heard.

Sings lifted his hands, palms out. He didn’t know what that was supposed to prove, if anything. No reason to think it would recognize any humanoid body language at all. It might understand him, or it might not—some of the odder creatures were able to understand human speech, and some were no different from regular beasts.

They stood there, for a few minutes, the man and the dead deer, and then it swung its head away, the long, smooth nasal bones pointing into the trees nearest the barn, and stamped its hoof again.

A skeletal doe melted out of the trees. She had an awkward, hopping gait, completely at odds with the ossuary grace of the buck. Sings could see immediately that her right front leg was broken. She held it hitched up in front of her, the naked hoof dangling awkwardly.

“Oh, you poor thing,” he said, and quite forgetting the enormous buck standing there, started towards her.

A warning rattle stopped him. He turned, and saw the buck eyeing him eyelessly, the head lowered just a little. He lifted his hands again.

“I’ll do what I can,” he told the bone stag. And then, hoping he wasn’t about to be spread-eagled on that gigantic antlered mass, he bowed deeply to the stag.

And straightened.

And waited.

They stood there for a long moment. The leaves whispered in the trees, in a brief, cool breeze, that chilled the sweat on Sings-to-Trees’ body.

The stag lifted its head.

Sings turned away. The skin between his shoulderblades crawled. He bowed to the doe, for good measure, and she gazed at him with empty eye sockets.

There was no flesh on her, there was nothing that could pull the face into any shape beyond the mute grin of a skull, but still, he thought he could see pain.

He knelt in front of her, and very carefully, took the injured leg in his hands.

He was shocked immediately by the warmth. This was no dead thing—this was living bone. The break was reasonably clean. He had wondered why, lacking muscle and skin to hold it in place, it hadn’t just fallen off. Now he saw that the bones were threaded through and around with the black webbing, and a thick skein of it, through the hollow center, was still attached.

Hmm.

Had this been a real deer, he wouldn’t have tried it. Such breaks were extremely difficult to fix—while setting the bone was straightforward enough, you had to keep them practically immobilized for weeks to keep them from breaking it again, and the captivity and stress killed them more surely than the break would. A wild deer could get by on three legs, and other than putting out food, there wasn’t much you could do that wasn’t worse than the injury. It was different with fawns. He could manage fawns, and although he couldn’t return them to the wild, more than a few half-tame deer in parks in the elven city had started life on his farm.

This one, though…gods.

“I can splint it,” he said to her, fairly sure she didn’t understand him. “Splint it, and wrap it, and put some plaster on it. You’ll have to stay off it if you can. You probably can’t. Um.” He was very aware of the stag’s not-eyes boring into the back of his head.

“Let’s start with that,” he said, and got up. The stag rattled a little, then stopped, as if embarrassed. Walking backwards, making “wait” gestures with both hands, he got inside the barn and began rummaging around for supplies with which to, once again, do the impossible.

“War is just not efficient,” said Murray.

This was such a typically Murray comment that Nessilka snorted with laughter, even under the circumstances.

They were standing in ranks on the top of the hill. Elves and humans stood in ranks at the bottom of the hill. In a few minutes, somebody was going to break and yell “Attack!” and the humans and elves would come up and the goblins would go down, and then it’d just be shouting and hitting and pointy things.

“Look at this,” he continued. “They’re going to charge up here, and we’re going to beat them back, and at the end of the day, we’ll probably still be up here, and they’ll probably still be down there. We both know it. The battle isn’t going to change anything, and it’s all for control of this stupid hill, which neither of us would give a rat’s hind end for if there wasn’t a war.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Nine Goblins»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nine Goblins» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nine Goblins» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.