Roughly ten minutes later there was another tremor.

Few become true pit-canaries. While the townsfolk dwell below, there is another stage, another extreme that only the most devout have courage or madness enough to explore.

Beyond the tract where the mattresses and bags are strewn there is another tunnel, stiflingly tight and perilously ragged, one bored by something cruder than even the crudest tool. Only those who have dared to squeeze through that aperture earn the stigma of pit-canary because, like their namesake, those birds go beyond.

As to what forged that tunnel, I could add my theory to the hundreds that have been posited before, but what would such a thing prove? The tunnel is somehow connected to the emerald light. I believe this. And I believe that both are the products of something even greater and stranger than both those things combined.

Somehow somebody in Evendale awoke something down there. Now that something is beginning to awaken all of us.

The change is undeniable. Everyone down here feels it, but because it is so indefinable we do not speak of it. We simply accept its presence within us, like a growing contagion.

This is a cold, unwanted revelation, like happening upon a lump in one’s breast or testicle; the kind of discovery that makes one yearn for normalcy, tedium, for all those ditchwater-dull afternoons and daily routines that we so foolishly felt needed to be stripped away by novelty and change. Yes, it is that kind of wordless knowledge that there is no going back. Even racing up to the sunlit yards of Evendale would be a small and flimsy defense. And so, we wait.

I’m told that early on some of the men wanted to place bright orange sawhorses before the mouth of that unmapped tunnel as a warning to keep away, but before they could return with their barricade, the mine had produced its own.

The vine sprouted from one carbon wall, drooped across the down-sloping chute, and then poked through the black rock of the opposite wall. Blooming out of this twisting verdant cable were five bellflowers, vibrantly red, as though colored by arterial blood that raced through transparent petals. Deeply fragrant; even the methane fumes were made sweet, so strong was their perfume. The flowers hung inversely. Set against that gaping hole in the mine wall they were positively incandescent, the beginnings of some new garden in paradise. I studied the flowers often, perched upon my plastic lawn chair, coughing into my sooty hands.

I watch the flowers and I wait. Wait for my father. Two weeks ago, much to my shrieking protests, he left the camp here on the tract and he became a pit-canary. He said he’d dreamed my mother had come to him through the emerald light and that she’d encouraged him to see what dwelt on the outer rim of that light. Dad said he believed the light was actually the breath of some living thing, large and ancient and wise. An entity that had been here long before we crawled out of the swamp, just down here sleeping, waiting . . .

He’d also said he thinks this creature, whatever it is, is calling us to descend farther and farther down so it can give us some new kind of fire, the kind that lights up the depths of space.

I’d asked him how he came to know this, but Dad couldn’t really say.

Only two pit-canaries have come back in the whole time I’ve been here, but it seems to be enough to keep people believing, waiting, wondering. The first was an elderly woman who’d owned a cake shop on Main Street. She said she’d heard trumpets and bells in that tunnel, then the green light had welled up to touch her, and for one brief but glorious moment she was able to hold her own heart in her hands. She’d said she tested it for heft and had determined that it wasn’t yet light enough, so she’d come back up to fast and pray. She stayed above. I never found out what happened to her.

The other pit-canary who returned only lived for a few seconds. He came crawling out of the tunnel screaming in agony. He screamed and he screamed. He even tore out the vine of bellflowers. When two of the men dragged him out they discovered that he’d been torn open, but the innards that spilled from his jagged and gaping wounds were fossilized; white and smooth and preserved, like the entrails of a marble grotesque.

Only after the commotion ended did someone comment about how the red bellflowers had already grown back across the tunnel mouth.

Another tremor.

And another.

It won’t be long now, whatever “it” is.

The bellflowers have begun to ring. Their chiming is open and almost without a source. They swing like their namesakes in a belfry. And like those chapel bells, these seem to rouse the faithful to service.

One by one the people began to crawl through the tunnel. Where they had once given a wide berth to avoid, they now scrambled and fought to penetrate. The emerald glimmer was now visible within the tunnel, cresting upward like a tide of foul sewer water. We both watched as the last resident wriggled toward that ill light.

Rita begged me to let her go, but I held her back. Impulsively, senselessly, she had wrestled that damned dress over her head, tugging it over her filthy T-shirt and jeans.

A short time later we felt the collapse just below us. It shook the ground. The chorus of screams from those below was muffled by the falling black rock but was no less terrible.

Is this what you lured all of them down there for ? I wondered.

“Dad!” Rita cried, over and over.

I shrieked for her to follow me into the rescue pod. Eventually she did. I shut the door, praying that the cave-in wouldn’t reach this upper level and that it ended swiftly. There was no oxygen in the tank, but we needed shelter from the mushrooms of black smoke that filled the tract. Chunks of coal smacked against the pod like a shower of stones. The light leaked up through the fresh fissures in the ground.

Eventually the thunder waned. I looked through the pod window, expecting to see only blackness. But there was a distinctive glimmer, greenish and persistent, even against the thick filter of coal dust.

I closed my hand over my mouth.

She pushed past me.

I followed her, choking on the fumes and dust.

The emerald light pushed through the collapsed tunnel, shining like a lamp covered with perforated black felt. For a long time we simply stood. Then something pressed through the piled rocks. It rolled near with patient velocity.

I turned to Rita, who was bolted in place. Terror blanched her face and made her jaw hang slack.

I took a step forward.

“No!” I heard my sister scream, seemingly from the far end of the world. “No, goddamn it!”

I reached down, picked up the luminous object, and turned back to Rita.

I rolled the object in my palm before halving it with a forceful twist.

“It’s from father,” I informed her with a knowledge that had bypassed even my own consciousness.

Rita reached for her half but quickly dropped her hand. She watched in mute but visible agony as I bit into the apple.

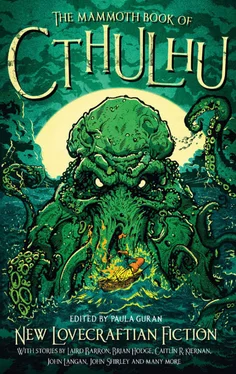

Don Webbviews his story, “The Future Eats Everything,” as a “Lovecraftian intersection of the cosmically strange and impersonal, and the personal and mundane. Lovecraft is seen as the prophet of the former and ungifted as to the latter, but in reality it is he that showed that true fear happens when the cosmic rubs its legs against the sleeping human in the bed of the mundane.” Webb’s most recent book is collection Through Dark Angles: Works Inspired by H. P. Lovecraft (Hippocampus Press). He has had sixteen books and more than four hundred short stories published. He lives in Austin, Texas, and teaches creative writing for the UCLA Extension Writers Program.

Читать дальше