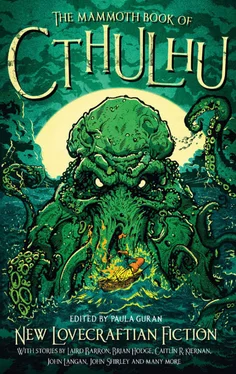

The Mammoth Book of Cthulhu

New Lovecraftian Fiction

Edited by Paula Guran

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by Robinson

Introduction: Who, What, When, Where, Why . . .

Paula Guran

This anthology has little to do specifically with Cthulhu and everything to do with “new Lovecraftian fiction.” But Cthulhu and the “Cthulhu Mythos” (more properly the “Lovecraft Mythos”) has become a brand name recognizable far beyond genre in every facet of popular culture: mainstream literature, gaming, television, film, art, music; even crochet patterns, clothing, jewelry, toys, children’s books, and endless other tentacled products . . . so one does what one can to sell books!

But, to answer the question posed . . . H. P. Lovecraft invented Cthulhu in 1926. The entity makes his first appearance in Lovecraft’s short story, “The Call of Cthulhu,” published in the pulp magazine Weird Tales in 1928. A small bas-relief of the creature is described in the story as:

“[A]sort of monster, or symbol representing a monster, of a form which only a diseased fancy could conceive. If I say that my somewhat extravagant imagination yielded simultaneous pictures of an octopus, a dragon, and a human caricature, I shall not be unfaithful to the spirit of the thing. A pulpy, tentacled head surmounted a grotesque and scaly body with rudimentary wings; but it was the general outline of the whole which made it most shockingly frightful.”

“Dead Cthulhu waits dreaming,” immured underwater in the “nightmare corpse-city of R’lyeh . . . built in measureless eons behind history” by the Great Old Ones, “vast, loathsome shapes that seeped down from the dark stars” to Earth. Cthulhu is a priest to these ancient aliens, but is also worshipped as a deity by some humans as are the loathsome invaders from space. Such devotion is based in superstitious ignorance, age-old familial ties, the promise of power, or the need to hedge their human bet: the Old Ones are supposed to return (or perhaps arise) someday . . . and that will be the end of humanity as a whole.

Since the name Cthulhu was, according to Lovecraft, “invented by beings whose vocal organs were not like man’s . . . hence could never be uttered perfectly by human throats,” and the author himself provided several varying pronunciations, there’s no “right” way to pronounce the name.

Cthulhu is, really, a symbol of “the vast unknowable cosmos in which all human history and aspirations are as nothing.” [S. T. Joshi, The Rise and Fall of the Cthulhu Mythos ]. And this is an important concept in the fiction of H. P. Lovecraft.

[Note: Much of the following is self-plagiarized from previous introductory essays.]

H. P. Lovecraft was, according to Fritz Leiber, “the Copernicus of the horror story,” and can be credited with at least being a father of weird fiction, if not its only sire.

Born in 1890, Howard Phillips Lovecraft was little known to the general public while alive and never saw a book of his work professionally published.

His father, probably a victim of untreated syphilis, went mad before his son reached the age of three. The elder Lovecraft died in an insane asylum in 1898. (It is highly doubtful that Lovecraft was aware of his father’s disease.)

Young Howard was raised by his mother; two of her sisters; and his maternal grandfather, a successful Providence, Rhode Island, businessman. His controlling mother smothered him with maternal affection, while also inflicting devastating emotional cruelty.

Sickly (probably due more to psychological factors than physical ailments) and precocious, Lovecraft read the Arabian Nights and Grimm’s Fairy Tales at an early age, then developed an intense interest in ancient Greece and Rome. His grandfather often entertained him with tales in the gothic mode and Lovecraft started writing around the age of six or seven.

Lovecraft started school in 1889, but attended erratically due to his supposed ill health. After his grandfather’s death in 1904, the family — already financially challenged — was even less well off. Lovecraft and his mother moved to a far less comfortable domicile and the adolescent Howard no longer had access to his grandfather’s extensive library. He attended a public high school, but a physical and mental breakdown kept him from graduating.

He became reclusive, rarely venturing out during the day; at night, he walked the streets of Providence, drinking in its atmosphere.

He read, studied astronomy, and, in his early twenties, began writing poetry, essays, short stories, and eventually longer works. He also began reading Jules Verne, H. G. Wells, and pulp magazines like The Argosy , The Cavalier , and All-Story Magazine .

Lovecraft became involved in amateur writing and publishing, a salvation of sorts. Lovecraft himself wrote: “In 1914, when the kindly hand of amateurdom was first extended to me, I was as close to the state of vegetation as any animal well can be . . .”

His story, “The Alchemist” (written in 1908 when he was eighteen), was published in United Amateur in 1916. Other stories soon appeared in other amateur publications.

Lovecraft’s mother suffered a nervous breakdown in 1919 and was admitted to the same hospital in which her husband had died. Her death, in 1921, was the result of a bungled gall bladder operation.

“The Horror at Martin’s Beach” was published in the November 1923 issue of Weird Tales , which became a regular market for his stories. He also began writing letters at an astoundingly prolific pace to a continuously broadening group of correspondents.

Shortly thereafter, Lovecraft met Sonia Haft Greene — a Russian Jew seven years his senior — at a writers’ convention. They married in 1924. As The Encyclopedia of Fantasy , edited by John Clute and John Grant, puts it, “. . . the marriage lasted only until 1926, breaking up largely because HPL disliked sex; the fact that she was Jewish and he was prone to anti-Semitic rants cannot have helped.” After two years of married life in New York City (which he abhorred and where he became an even more intolerant racist) he returned to his beloved Providence.

In the next decade, he traveled widely around the eastern seaboard, wrote what is considered to be his finest fiction, and continued his immense — estimated at 100,000 letters — correspondence through which he often nurtured young writers.

Outside of letters and essays, his complete works eventually totaled fifty-odd short stories, four short novels, about two dozen collaborations or ghost-written pieces, and countless poems. Lovecraft never really managed to make a living. Most of his small livelihood came from re-writing or ghostwriting for others. He died, alone and broke, of intestinal cancer on 15 March 1937, and was buried at Swan Point Cemetery in Providence. Forty years later a stone was erected to mark the spot by his admirers. It reads: “I am Providence.”

Lovecraft’s literary significance today can be at least partially credited to this network with other contemporary writers. Letter writing was the “social media” of his time, and he was a master of it. Although he seldom met those who became members of the “Lovecraft Circle” in person, he knew them well — just as, these days, we have friends we know only through the Internet.

H. P. Lovecraft was probably the first author to create what we would now term an open-source fictional universe that any writer could make use of. Other authors, with Lovecraft’s blessing, began superficially referencing his dabblers in the arcane, mentioning his unhallowed imaginary New England towns and their strange citizens, writing of cosmic horror, alluding to his godlike ancient extraterrestrials with strange names, and citing his fictional forbidden books of the occult (primarily the Necronomicon of the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred): the Lovecraft Mythos — or, rather, anti-mythology — was born.

Читать дальше