“Do you see now?” Captain Thomas shrieked. “Do you see how sweetly she sails?” His long gray hair whipped in the wind like snakes, and his sharpened teeth gleamed with each flash of lightning. His eyes caught the red fire of the sinking sun.

The wind-wagon roared past Charley, its furious wheels spattering him with dark droplets. He tasted copper and salt.

Now the wagon drove to the northeast, aiming for a horse that was spinning, rearing, and bucking. The horse’s small rider was clinging to the reins with one hand and a Spencer carbine with the other.

Charley got to his feet. He wanted to call out to Joshua. But he knew the boy wouldn’t hear him over the wind, the thunder, and the roar of the wagon.

There was nothing to be said to him now, anyway.

As the wind-wagon bore down, the horse bucked hard and jumped away. Joshua flew into the air, tumbling as the Spencer shot fire, and then the narwhal tusk caught him in the back. The Spencer fell away, and the tusk spiked out through Joshua’s chest.

Captain Thomas shrieked again, and the wind-wagon came about, rising onto two wheels. Then it plunged back down the hill, roaring past Charley once more.

Joshua slid back on the tusk and fetched up against his father. He looked down at Charley as they flew by.

Charley could not read Joshua’s expression. But he saw that the boy’s freckled cheeks were still wet.

The wind-wagon dove down the slope and back up the hill to the south. As it reached the top, it was illuminated by yet another flash of lightning. The sails billowed and warped, and Charley heard Captain Thomas shriek one more time.

Then the rain came in a torrent, and Charley’s eyes filled with water as the wind-wagon disappeared.

The rain lasted long enough to wash the dark droplets from Charley’s skin and to soak his clothes. Then the thunderclouds began to break and slip away even more quickly than they had come. The moon, almost full, rose in the east as the last vestige of the sun slipped away in the west. Its cool light let Charley see where he walked as he began to trudge north.

He whistled for Bird King. But instead, Joshua’s roan mare and Black-beard’s sorrel gelding came up to him, whickering.

“I don’t want to ride either of you,” Charley said. “But you may walk with me, if you like.”

They had almost reached the top of the hill when Charley heard another whistle. He looked back down the slope and saw Uncle JoJim approaching on Calico Girl. They were leading the other gelding on a rope, moving at a walk. The shotgun was back in its scabbard. And Uncle JoJim was wearing his hat again.

Charley waited until Uncle JoJim drew near. Then he said, “You might have come sooner.”

Uncle JoJim stopped Calico Girl beside Charley. “As I have said, I don’t want to make Calico Girl run anymore.”

“But I needed you,” Charley said.

Uncle JoJim gave him a stern look. “No, you didn’t. Besides, if you had done as I instructed, you would have been far away.”

Charley knew it was true. “I apologize, Uncle JoJim. I should not have disobeyed.”

Uncle JoJim shrugged. “You’ll know better next time. Now, take the bags from those horses and leave them. We don’t want what’s inside. Then tie one of the horses to the one behind Calico Girl. You may ride the other.”

Charley frowned. “I will only ride Bird King.”

“Disobeying yet again.” Uncle JoJim sighed. “All right, tie them both. You may walk.”

Charley did as he was told, and then they all started over the hill. As they topped the rise, Charley saw Bird King a little way down the slope, grazing.

“Bird King!” Charley called. “Why didn’t you come when I whistled?”

Uncle JoJim chuckled. “He’s angry. I can see the wound near his tail. You didn’t go home when I said to go home, so Bird King was shot.”

“I’m sorry, Uncle JoJim,” Charley said.

“Don’t tell me. Tell him.”

Charley whistled once more, and this time Bird King came. Uncle JoJim dismounted, examined the wound, and said it wasn’t deep. And the bullet had not remained in the flesh.

“But it still hurts him,” Uncle JoJim said, swinging up onto Calico Girl again. “We’ll put a poultice on it when we reach the reservation. For now, it’s up to him whether he lets you ride. If he does, I wouldn’t ask him to run.”

Charley put his hand on Bird King’s soft nose. Bird King tossed his head, but then let Charley grasp his mane and pull himself up. Charley untied the rope that was still around Bird King’s neck, and he let it fall.

As they started northward again, Uncle JoJim said, “I suppose you may be saddened because of the boy.”

Charley brushed water from Bird King’s mane. “He was just a boy. Like me. It’s hard to know what I should think.”

“He was a boy,” Uncle JoJim said. “But not like you. And you’ll live through many times when it will be hard to know what to think.”

They rode in silence for a quarter mile. Then Charley asked, “Is Captain Thomas one of the ghosts Grandmother spoke of?”

“No. Ghosts are easier to understand.”

“But the black-bearded man shot him with your shotgun, and he didn’t die. Not even after falling onto the fire.”

“It was only birdshot,” Uncle JoJim said. “And he wore a thick coat. Also, he didn’t lie on the fire for very long.”

“So he’s just a man?”

Uncle JoJim adjusted the brim of his hat. “That would be easier to understand, too. But I’m sure of one thing: He came to pay his debt for my arm. I can’t guess how he knew this would be the right time. But it’s done. So now he’s gone again.”

That all made a small bit of sense to Charley. “I’m glad,” he said.

Uncle JoJim looked behind them at the tied horses. “Yes. And along with our chickens, we have three ponies to replace those the Cheyenne stole last month. Allegawaho will be pleased. Everyone will be.”

Charley pondered. “So now they might consider us to be Kaw?”

Uncle JoJim shook his head. “No. We are what we are.” He looked toward the moon. “What we are is good enough.”

That made a bit of sense to Charley, too.

“At least we aren’t crazy,” he said.

Uncle JoJim shrugged yet again, and his empty sleeve flapped. “Not yet.”

Bird King began to trot then, of his own will. He and Charley led the way home through the sea of grass.

WHAT MY MOTHER LEFT ME

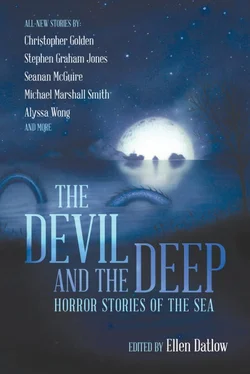

ALYSSA WONG

The sky above Nag’s Head is stained an uneasy shade of gray by the time we pull up to my parents’ North Carolina beach house. Beyond the dunes and waving field of sea grass, the water is sharp and choppy, the color of slate.

“Shit,” says Gina, climbing out of the Range Rover. She shades her eyes, her long, lavender-dyed hair flapping across her face. The wind slaps us both with the salty, thick smell of the ocean. “You brought the keys, right?”

Her eyeliner is perfect, as usual. I can’t believe she drew it on in the passenger seat while I was doing ninety on the I-40, eager to put as much distance between us and Duke University as possible.

“Way ahead of you,” I say, fishing the house keys out of my pocket. The key fob is a piece of driftwood, carved with the words HOME SWEET HOME and a pair of flip-flops. It’s about as tacky as the rest of the house’s decor. We trudge up the wooden stairs, wiping our feet on the faded welcome mat printed with migrating birds. There’s a thin film of salt on the lock.

I sort through the keys, looking for the right one. I don’t realize my hands are shaking until Gina drapes herself over me.

Читать дальше