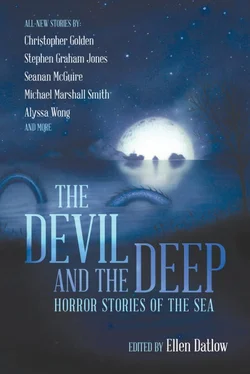

THE DEVIL AND THE DEEP

HORROR STORIES OF THE SEA

Edited by Ellen Datlow

Thanks to Stefan Dziemianowicz and to my editor, Jason Katzman.

Igrew up loving the ocean. My family went to New York’s Rockaway Beach for many summers when I was a child and through my teenage years. I loved the beach, lying on the sand, baking in the sun (pre-cancer scares) with my friends, the smell of the tar in the parking lots—and of the ocean—and body surfing in the waves. I also went fishing with my dad (in lakes and ponds), and even went on a deep-sea fishing trip with a friend in my early twenties (we caught nothing).

But in 1975, something happened. I went to see Jaws . It scared me so badly that I had a difficult time going into the ocean after that. For a (very) brief time, I was even fearful of lakes and swimming pools. Then, in 1977, The Last Wave was released, about the end of the world heralded by a tsunami on a coast of Australia. Those two movies made me realize that the sea and the simple act of swimming in it could be frightening, even terrifying.

We, like all other forms of life, come from the sea, and yet we’re intimidated by it. Why? One reason could be that the seas are more vast on our planet than the land we live on, and 95 percent of the sea is still unexplored. It’s a natural human tendency to fear the unknown, and our relative ignorance about the sea fosters superstitions, myths, and legends about it and what might inhabit it (sirens, sea monsters, forms of organic life that we can’t even begin to comprehend because the conditions in which they flourish are inimical to human life). H. P. Lovecraft populated the spaces between universes with extra-dimensional monsters, but he also populated the sea with them in The Shadow Over Innsmouth , a story that serves as a touchstone for a lot of horror fiction written since. Lovecraft, like numerous other writers (William Hope Hodgson in particular), saw in the vastness and alienness of the sea the same potential for horror that has persuaded writers since the dawn of the tale of horror to infest the dark with monsters and boogeymen. The sea is a watery terra incognita, a huge blank canvas that invites writers to imagine horrors onto it.

But, come on. In reality it’s only water, so why should we fear large bodies of it? Well, those sharks, especially the Great White—a predator’s dream, a swimmer or surfer’s nightmare. Also, those mysteries in the deep blue sea—awful mysteries like eons-old fish that shouldn’t exist today but apparently do. Then there are fish like the dragonfish, with its big teeth and hideous face and the black seadevil, with sharp teeth, both found in the deeps of the Mariana Trench.

Another aspect of what makes the sea so horrifying: it seems hostile to us (although, really, it’s as indifferent to human existence as Lovecraft’s monsters are). We’re of it, but we can’t live in it. One can drown in a minimal amount of water, but it’s more likely that a riptide will drag unwary swimmers out to sea, or you might just develop a cramp, preventing you from getting back to shore with no lifeguard to save you.

We build ships to sail upon the ocean, deluding ourselves that we can master it, but shipwrecks prove that some of our sturdiest inventions are at the mercy of the sea. People (and sometimes vessels) lost at sea are often never found: the sea is like a vast ravening maw that can swallow us in one bite.

Remaining on shore is no guarantee of safety, either. If we stray too near the sea, it can pull us from our safe haven on land (sort of like the monster under the bed reaching up to grab us). And we’ve all witnessed the damage tsunamis can wreak on shorelines around the world, killing thousands. There’s a lot of talk about global warming these days, and the consequence: rising sea levels. As the sea encroaches on the world that we’ve built for ourselves, it has the potential to sweep away everything that human progress and civilization have created—everything that our species stands for. The sea coughed us up, but some day it’s going to reclaim us, and there’s precious little that we can do about it. We are puny. It is monstrously vast and overwhelming. It makes us realize that, on our planet, we are only temporary, while the sea is permanent.

The stories in The Devil and the Deep cover a range of aspects of the sea and the shores around it, from obvious monsters to the mysterious; there are tales of shipwrecks, haunts, monsters—human and inhuman—one story even taking place on what was once an inland sea, long gone. All these tales have been conjured up from the imaginations of the fifteen contributors. Each is basically about people, and how they deal with the mysterious entity surrounding us.

Above the sea, the railway ran; a hundred yards inland a 4x4 stood empty on a dirt track, keys still in the ignition. There was no one inside, no sign of a struggle, and no witnesses. That whole part of the coast is hills and empty fields, with the odd farmhouse hidden in bristling crops of pine.

A rainy sky, and the tide was in, the dull grey sea gnashing at the edge of the shingle beach.

The 4x4 belonged to one Robin Gaunt. Police Constable Lewis popped into the Harbour Café that morning to ask if I knew him. The Harbour’s the most popular café here—both locals and tourists love it. I’ve part-timed at half the other places in town, too—work here tends to be seasonal, so you take whatever’s going—which means there isn’t much I don’t hear about. Clive makes me his first port of call whenever he wants to know something. Fringe benefit of being his girlfriend, I suppose.

Around here people are like the tide: some flow in, some flow out. Ten, fifteen years ago there’d been an influx of New Age types, all coming to commune with Nature; Robin had been one of them. Now they were being displaced in their turn, by urban professionals buying second homes. Frankly, I was missing the hippies already.

I told Clive most of what I knew. Robin popped into the Harbour once or twice a week for a Full English or a sandwich, but didn’t have much motivation beyond getting high and saying “wow, man” at the scenery a lot. The scenery around here is pretty “wow”—we’re on a nice stretch of coast, with mountains all around—but after a while, you hardly notice it. Unless you’re like Robin.

We’d meet some evenings, when Clive was on nights. Look, I’m young and I get lonely. Around here, you find some company or you climb the walls. We smoked some weed—usually out in his car—and slept together twice. The first time we were stoned, and I was going through a bad patch with Clive. The second time was a mistake, and I told Robin it wouldn’t happen again. He accepted that, and my statement that I still wanted to be friends. Go with the flow was his philosophy: that was how he’d ended up here. And why I liked his company. He was easy-going, didn’t make demands. I told Clive none of this, of course. As a small-town copper, he tends to see things in black and white.

Clive had been to Robin’s rented cottage, but no one had answered the door. No, he hadn’t broken it down—this wasn’t the big city and all he had so far was an empty car. Robin had probably smoked too much draw and walked back into town instead of driving along the narrow, winding, ill-lit coastal roads. He was either at a friend’s house or so comatose he hadn’t heard Clive knock.

Читать дальше