I follow links and fill my search engine with key words. I gather data as if it were the ingredients for a cure. I don’t even notice George when he enters the room.

“We could get out of town,” he says, sipping from his drink.

“Should you be drinking?” I ask. “Until we know more about this, you need to be careful.”

“Bullshit,” George says.

“But your immune system might be compromised, or the virus could affect the liver.”

“Don’t care,” George says. “I spent my whole life following rules, and I’m still fucked. Now, what do you think about getting out of town?”

“I suppose I could get time off work.”

“No,” George says. “I’m not talking about a vacation. I’m talking about moving. If I’m here, then someone could see me… acting up. Maybe we could sell our places, head north. I just keep thinking my family is going to find out. It scares the shit out of me. I can’t even function.”

“I can’t retire,” I say. “Not for another couple of years at least.”

“We’ll find jobs.”

“At our ages?”

“Well, I don’t know!” George shouts and throws his arms wide, sloshing whisky over the lip of his glass. “Am I supposed to just hide in here all day, waiting to see what new atrocity is lurking around the corner?” He sits on the arm of the sofa, staring at the splash of liquid pooling on the floor. “I suppose I could go by myself.”

The suggestion creates a painful vibration in my ribs. He doesn’t mean to be cruel. I know it.

“Don’t say that.”

“This fucking world,” George says. “I’m finally happy and then this . I thought Eugie would be my downfall, maybe Barry, but a fucking mosquito?”

“If you want to move, really want to do it, we’ll find a way. We can go anywhere you want.”

“I don’t care where,” George says.

“Then let’s leave,” I say. “Let’s get in the car and drive. We’ll head north until we find a place.”

“If you’re serious, I’ll need time to make arrangements,” George says. His mood is not bright, but the darkest edges are off of it. “I can’t just vanish or Eugie will release a squad of investigators to find me so the divorce proceedings aren’t inconvenienced.”

“Tell me when, and I’ll be ready.”

“A couple of days? I have an old friend who owns a B&B in Colorado. We’ll be okay there until we have a plan.”

Barry crossed to the dining table, a table George and I rarely used for anything as we tended to eat on the sofa in front of the television. He grasped the back of a chair upholstered in fawn-colored suede and shook his head.

“He shouldn’t have kept this from us. We’re his family. Family is everything.”

“He was embarrassed,” I said. “Once they had identified the virus, and we knew his seizure wasn’t a one-time event, he didn’t want to leave the apartment. Then after the people vanished at Holly Beach, George started to panic. Families of the missing came forward. They talked about the dancing and the chanting. It was the first connection between the Gibbet Virus and the disappearances. It hit him extremely hard.”

“We should have been told,” Barry said, rocking his belly against the back of the dining chair as if attempting to discreetly hump the piece of furniture. “ We would have gotten him the help he needed. We’d have gotten him great doctors. The best doctors. He wouldn’t have just been walking around waiting for that thing to come along. He’d be alive right now, and my mother wouldn’t have to worry about her future.”

George had been right about his family. They would have declared him unstable and likely would have institutionalized him. He was their golden goose, and he’d gotten out of the pen. The sickening unease I’d felt since Barry’s arrival intensified. Hot and cold static avalanched from my face to my stomach and a tremor ran through my muscles. He was accusing me of negligence, incompetence, but this wasn’t the grief of a mourning child, it was the disgust of a disappointed heir.

This privileged brat couldn’t imagine what I’d lost with George. Why should he? To him, his father was an old piece of furniture, something to stick away in a basement or attic until it could be sold at auction. He didn’t understand the losses of aging. He couldn’t be bothered to see how amazing it was to actually gain something so late in life, something so important.

Everything I knew about growing old told me I would lose and lose, and then I would die. My body had changed. My cells refused to repair themselves; they became bungling and languid. My senses changed, became less than they were. The world looked different. It sounded different. It felt different. Everything was harder and colder to the touch. I accepted these losses as natural, as part of my flawed human existence.

But to gain something, to find someone at this stage of my life?

It was unexpected, because nothing I’d witnessed had prepared me for it. How could I expect the bloated trust-funder to understand exactly how precious George had been to me?

I couldn’t, and I knew I couldn’t, and I knew I shouldn’t have to.

“I’ve told you what you need to know,” I said.

Barry continued to hump the back of the chair. “You haven’t told me anything. Nothing that can be proven.”

“You are welcome to speak with the authorities, but right now, I’m mourning the man I loved, and I find it completely fucked up for you to come into my home and accuse me of… What exactly do you think I did?”

He shrugged and looked away. “You let him die,” Barry said.

His tone was so dismissive, so much like a teenager’s response of “Whatever,” that I wanted to punch him in the face. He gave up on the chair and turned back to the window.

“Is this where it happened?” he asked, gesturing to the beach beyond the glass.

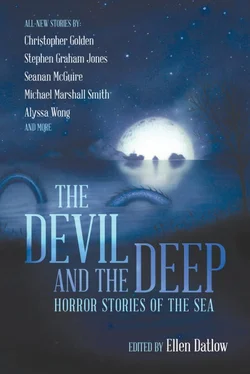

The enthralled crowd ambles in a line over the gulf, appearing like saviors walking on water beneath a radiant moon. Amid the perfume of salted air, a deeper, fouler odor rises: the rot of fish; the pulsing stink of seaweed. Straining my vision, I note a glow drawing a path into the gulf, like a mesh of pale white wires. This mesh provides a bridge, over which the throng slowly march.

I shook my head. Sudden misery clotted in my throat, and I squeezed my lips tightly to keep from making a sound. Tears coated my eyes. Pointing to the south, I managed to say, “About half a mile.”

“But you have no proof he was there. He could be in the Bahamas.”

“He was there,” I said. A plea began to chant in my mind: don’t make me say this, don’t make me.

“None of the witnesses could definitively identify my father as one of the victims. Not one. I’ve asked them.”

“That’s not true,” I said. “I can.”

The information startled Barry. “What?”

“I saw him on the beach. I saw that thing in the water. I watched George die.”

My panic as I search the apartment is venom, stinging and spreading through my system as I shout George’s name. He never came to bed. He was planning our escape from Galveston and was making a list of people he needed to contact and a set of talking points to keep his story straight. He tells me to get some rest, but I can’t sleep. After thirty minutes, I get up and join him at the dining room table, where I notice he is still dressed. He’s so consumed with his plans that he’s forgotten to indulge his nudity. We chat until he shoos me off so he can concentrate.

Читать дальше