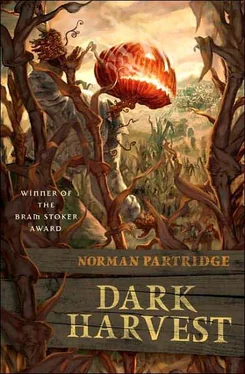

Norman Partridge

Dark Harvest

A Midwestern town. You know its name. You were born there.

It’s Halloween, 1963… and getting on toward dark. Things are the same as they’ve always been. There’s the main street, the old brick church in the town square, the movie theater — this year with a Vincent Price double-bill. And past all that is the road that leads out of town. It’s black as a licorice whip under an October sky, black as the night that’s coming and the long winter nights that will follow, black as the little town it leaves behind.

The road grows narrow as it hits the outskirts. It does not meander. Like a planned path of escape, it cleaves a sea of quarter sections planted thick with summer corn.

But it’s not summer anymore. Like I said, it’s Halloween.

All that corn has been picked, shucked, eaten.

All those stalks are dead, withered, dried.

In most places, those stalks would have been plowed under long ago. That’s not the way it works around here. You remember. Corn’s harvested by hand in these parts. Boys who live in this town spend their summers doing the job under a blazing sun that barely bothers to go down. And once those boys are tanned straight through and that crop’s picked, those cornstalks die rooted in the ground. They’re not plowed under until the first day of November. Until then the silent rows are home to things that don’t mind living among the dead. Rats, snakes, frogs… creatures that will take flight before the first light of the coming morning or die beneath a circular blade that scores both earth and flesh without discrimination.

Yeah. That’s the way it works around here. There are things living in these fields tonight that will, by rights, be dead by tomorrow morning. One of them hangs on a splintery pole, its roots burrowing deep in rich black soil. Green vines climb through tattered clothes nailed to the pole and its crosspiece. They twist through the legs of worn jeans like tendons, twine like a cripple’s spine through a tattered denim jacket. Rounded leaves take succor from those vines like organs fed by blood vessels, and from the hearts of those leaves green tendrils sprout, and the leaves and the vines and the tendrils fill up that coat and the arms that come with it.

A thicker vine creeps through the neck of that jacket, following the last few inches of splintery pole like a backbone, widening into a rough stem that roots in the thing balanced on the pole’s flat crown.

That thing is heavy, and orange, and ripe.

That thing is a pumpkin.

The afternoon sun lingers on the pumpkin’s face, and then the afternoon sun is gone. Quiet hangs in the cornfield. No breeze rustles the dead stalks; no wind rustles the tattered clothes of the thing hanging from the pole. The licorice-whip road is empty, silent, still. No cars coming into town, no cars leaving.

It’s that way for a long time. Then darkness falls.

A car comes. A door slams. Footsteps in the cornfield — the sound of a man shouldering through brittle stalks. The butcher knife that fills his hand gleams beneath the rising moon, and then the blade goes black as the man bends low.

Twisted vines and young creepers root at the base of the pole. The man’s sharp blade severs all. Next he goes to work with a claw hammer. Rusty nails grunt loose from old wood. A tattered leg slips free… then another… and then a tattered arm….

The thing they call the October Boy drops to the ground.

* * *

But you already know about him. After all, you grew up here. There aren’t any secrets left for you. You know the story as well as I do.

Pete McCormick knows the story, too… part of it, anyway. Pete just turned sixteen. He’s been in town his whole life, but he’s never managed to fit in. And the last year’s been especially tough. His mom died of cancer last winter, and his dad drank away his job at the grain elevator the following spring. There’s enough rotten luck in that little sentence to bust anyone’s chops.

So it’s not like the walls have never closed in on Pete around here, but just lately they’ve been jamming his shoulders like he’s caught in a drill press. He gets in trouble a couple times and gets picked up by the cops — good old Officer Ricks in his shiny black-and-white Dodge. First time around, it’s a lecture. Second time, it’s a nightstick to the kidneys. Pete comes home all bruised up and pisses blood for a couple of days. He waits for his old man to slam him back in line the way he would have before their whole world hit a wall, maybe take a hunk out of that bastard Ricks while he’s at it. But his father doesn’t even say a word, so Pete figures, Well, it looks like you’re finally on your own, Charlie Brown, and what are you going to do about that?

For Pete, it’s your basic wake-up call. Once and for all he decides he doesn’t much care for his Podunk hometown. Doesn’t like all that corn. Doesn’t like all that quiet. Sure as hell doesn’t like Officer Ricks.

And maybe he’s not so crazy about his father, either. Summer rolls around and the old man starts hitting the bottle pretty steady. Could be he’s noticed the changes in his son, because he starts telling stories — all of a sudden he’s really big with the stories. We’ll get back on our feet soon, Pete. They’ll call me back to work at the elevator, because that chucklehead Kirby will screw everything up. That gets to be one of Pete’s favorites. Right up there with: I’m going to quit the drinking, son. For you and your sister. I promise I’ll quit it soon.

It’s like the old man has a fish on the line, and he’s trying to reel it in with words. But Pete gets tired of listening. He’s smart enough to know that words don’t matter unless they’re walking the hard road that leads to the truth. And, sure, he can understand what’s going on. Sure, the nightstick that life put to his old man makes the solid hunk of oak Officer Ricks used to bust up Pete look like a toothpick. But understanding all that doesn’t make listening to his old man’s pipe dreams any easier.

And that’s what his father’s words turn out to be. The bossman down at the elevator never calls, and the old man’s drinking doesn’t stop, and things don’t get any better for them. Things just keep on getting worse. As the summer wanes, Pete often catches himself daydreaming about the licorice-whip road that leads out of town. He wonders what it would be like out there somewhere else… far away from here… on his own. And pretty soon that road finds its way into another story making the rounds, because — hey — it’s September now, and it’s about time folks started in on that one crazy yarn everyone around here spins at that time of year.

Pete catches bits of it around town. First from a couple of football players waiting to get their flattops squared at the barber shop, later from a bunch of guys standing in line at the movie theater one hot Saturday night. And pretty soon the story picks up steam at the high school, too. Again, Pete only hears snatches of it — in the bathroom out back of the auto shop where guys go to sneak cigarettes, in detention hall after school — and, sure, it’s pretty crazy stuff, but the craziest thing is that those snatches of conversation all fall within the same parameters, and that simple fact is enough to start Pete thinking this might be the rare kind of story that actually makes the trip from the campfire to the cold hard street.

“Got me a bat. Brand new Louisville Slugger.”

“That ain’t what you need. It’s too hard to swing a bat when you’re on the run, and you’re too slow as it is, anyway. Just look at that table muscle hanging over your belt. You couldn’t catch my great-great grandma rolling her ass uphill in a wheelchair with a couple of blown tires if your life depended on it.”

Читать дальше