After she no longer had access to Clay at all, how many more weeks — days, even — before she began fabricating entire reports, to keep from being recalled home? Turn his case history into fiction, just to avoid giving up on the idea of being part of it?

Sarah’s hand, warmed from the mug, found its way to hers; lingered and gave a squeeze before withdrawing.

“Have you thought of hypnotherapy for him?” Sarah said.

“Not seriously, no.” It was nothing for which she had ever trained. And while it had its merits, she had reservations that it would even be appropriate. Uncovering a forgotten past was not the issue, and posthypnotic suggestions generally worked better on concrete behavior patterns, not overall ways of relating to the world; thou shalt not smoke, thou shalt not eat to excess.

“He’s big on finding out what that chromosome triplet means, you know,” Sarah said.

“Trisome.”

“Hmm?”

“It’s called a trisome.”

“Whatever.” Sarah gulped at her coffee. “I don’t think Clay cares half as much what it’s called as he does finding out why it’s happening.”

“Well, don’t we all.”

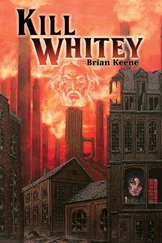

“And not just to him, but to each of them. You know, ever since I talked to him in that factory —”

The factory; now there was a blister to poke. Clay had let Sarah share his inner sanctum when he probably would have waved his chair at Adrienne until she retreated. Jealous? Hell yes.

“ — and he told me about the moths, that whole biological and environmental agenda under the surface, you know who I’ve kept thinking about?”

Adrienne gripped the wheel. This could only be weird. “Who?”

“Remember Kendra Madigan?”

She drew a blank for a moment, and then it hit her, hit her hard. “You’ve got to be kidding.”

“No. I’m not. It might be an interesting thing to try with him, if he’d want to.”

Adrienne, shaking her head, was adamant. “ Interesting. That’s a blithe way to put it. Especially when something like that is likely to do more harm than anything.”

But this was Sarah she was talking to; typical Sarah, who now and then clung to the oddball and superstitious because she wanted to believe in a shortcut, and she would not be dissuaded. They saw eye-to-eye on much, but here they parted company.

They had heard of Kendra Madigan even before she had come to Tempe for a lecture and debate at the university a year and a half ago. She had been written up in a one-page article Sarah had seen in Newsweek , and Psychology Today had humored her if nothing else.

A professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and a practicing hypnotist and psychologist, Kendra Madigan had written a book in which she claimed to have pioneered a hypnosis so deep it was possible to access the collective unconscious, the species memory that transcended the individual. No one of much note took her seriously, dismissing the technique as so much New Age hokum, although they stopped short of accusing her of fraud. She was, at worst, deluded, her ideas all the more controversial for her use of natural hallucinogens on some subjects. Predictably enough, her reception at Arizona State had been mixed, both enthusiastically pro and skeptically con.

Naturally, Sarah had been enthralled.

“You know what it’s like?” Sarah asked. “It’s like you’re just giving lip service to Carl Jung, and not really putting your money where your ideology is. How can you anchor yourself in Jung like you do and deny the collective unconscious?”

“I never said I was denying it. Did I ever once say that?” Adrienne gripped the wheel harder. This was good, actually. Kept her from dwelling on Clay. “I think it informs most people on a preverbal level, symbolically, maybe in dreams. But you can’t convince me someone can give it a voice and ask it questions. That comes close to being as ludicrous as psychics who claim they channel twenty-thousand-year-old entities.”

“Oh, forget it.” Sarah drew together with a frown. “We’ve had this argument before.”

“It’s not an argument, it’s a discussion.”

“Whatever it is, I’m not budging.”

Good for you, Adrienne thought. One of us should be sure of herself.

She took her eyes off the highway as dawn struggled, let her gaze drift left, to the mountains. Great vast ranges of rock and earth, they looked so tame from here. Snow-drenched peaks sat wreathed in cataracts of cloudy mist like Olympian dwellings.

It was right that Clay had come this direction. Had she been forced to track him, she would have known instinctively. Deserts and mountains, the refuges of hermits… these called to him with a voice clearer than that of any human being. He professed to be an atheist but she was not convinced he meant it, seemingly compelled to touch something so great it might destroy him. Or maybe it was because he was so inefficient at destroying himself. Either way, he was a believer in search of a higher power.

They picked their way through Fort Collins, following the sketchy directions Clay had provided; found a route that led out the other side of town, to the northwest, toward the foothills at the base of a mountain drive. The city had thinned to its barest elements, the final fringes before civilization ended.

He had called from a pay phone at an all-night diner and gas station, a rustic outpost set amid generations of pines. They found him inside at a booth, as far from the other early diners as he could get, everyone under a warm comforting miasma of pancakes and cinnamon rolls, coffee and sausage gravy.

Clay said nothing as they approached, laced his hands around a steaming cup; she wondered how many times it had been filled, if that glaze in his eyes was due to caffeine or something deeper.

Adrienne slid into the booth across from him.

Sarah hitched her mittened thumb back over her shoulder. “Why don’t I head over to the counter awhile, okay?”

“That’s all right,” Clay said, “you can stay.”

"No,” Adrienne said, looked at Sarah. “Go on, it’d be best if we were alone.”

She complied, and Clay raised his head, his eyebrows, in mild surprise at her take-charge mood. He looked dreadful, paler than during his final visits, with days of stubble and his hair falling toward his eyes, sweaty and matted from two nights beneath the stocking cap beside him.

“If you called me because you need a taxi,” she said, “then I’m afraid I may have to leave without you. If you called me to talk… I’m here.”

It came close to an ultimatum, tough talk, but the time had come for that. It was the push of the crowbar that got the story started, interrupted by a waitress, and she took coffee only. He told her about Friday night, some pitiful encounter with Erin. She tried to listen with professional distance but things had gone too far. She pictured the two of them on that floor, too crippled to even hold each other — the most heartbreaking image she had yet associated with him, worse even than the authoritarian abuses by his father; worse than the boy given permission to cry, just the once, for his dead baby sister and discovering he could not.

He told her of hitting the road again, of walking into Fort Collins. Of the record store. And there was remorse in his voice, his eyes; genuine remorse, held in check of course, but present, and that was something to cling to.

“I just kept hitting him,” he whispered. “I don’t know why.”

And as long as he felt bad about it, that made it all right? No, it didn’t. Some kid whose worst offense was poor public-relations skills was dead or hospitalized. Yet all she could do was analyze how Clay might be kept in the clear. He had paid with anonymous cash; the shop’s only other customer was behind him and would give a poor description; he had worn gloves and left no prints on the plastic carousel. He might never be connected with this.

Читать дальше