“I have a flight at Logan to catch,” she said, but froze when she saw Randolph Palmer looking at her as she had always imagined Catholics would look at the Virgin Mary while praying to her.

“I wanted to ask you something,” he said. “They came and told me even before he got like this that he had things wrong with him, things he was born with inside that didn’t come from his mother or me, neither one. I know you knew him then, before. These people here, they didn’t, none of them. I want you to tell me if you can… would he have ended up the way he was no matter what? I know sometimes I probably didn’t raise him the way I should’ve, but… that wouldn’t’ve made any difference, would it?”

She tossed her purse in through the door, cocked an elbow onto the roof as she leaned there and met Randolph Palmer’s eyes. He was a needy old man, come to seek absolution in what was most likely his final chance. How many years had he wrung his knotty hands and wondered if only he had done things differently? She should have been kinder than she felt, but if the temptation was there, so too was the thought of that small hand over a burning toy lamb, and it burned so much brighter.

“We’ll never know, will we?” she said. “I still live with that.”

“What about me?” He was close to pleading. She could see behind his eyes to all the fears that pooled there, how little time he had left to make his peace with a ruined son and how little progress he had made.

“You made your bed,” she told him. “Now die in it.”

She left him standing on the lot, alone and small at the end of a lengthening shadow at the close of a dismal day, and for another year she drove away hoping that Clay was where he wanted to be, at last, if only in his mind. And she thought, too, of all those babies born with the identical defect. Six hundred and eighty-three, the last she had heard, but that had been nine years ago. They would be in grade school now, and for them she prayed for patient teachers and persistent friends and, most of all, parents who had not confused love with something else, something tyrannical.

She thought of the last thing she had said to Randolph Palmer, then echoed his sentiments exactly.

I shouldn’t have done that.

But she did not turn around.

The damage was already done.

There are few pains as sore as once having seen, guessed, felt how an extraordinary human being strayed from his path and degenerated.

— Friedrich Nietzsche

Beyond Good and Evil

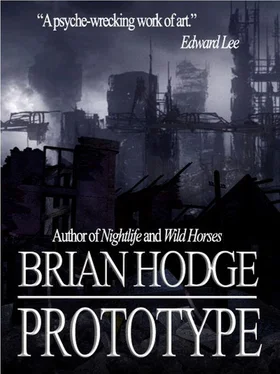

Called “a spectacularly unflinching writer” by Peter Straub, Brian Hodge is the author of ten novels, close to 100 short stories, and three collections of short fiction. Recent books include his second crime novel, Mad Dogs , and his upcoming fourth collection, Picking The Bones .

He lives in Colorado, where he’s at work on a gigantic new novel that doesn’t seem to want to end, and distracts himself with music and sound design, photography, Krav Maga, and organic gardening.

Connect with him online through his web site ( www.brianhodge.net), his blog ( www.warriorpoetblog.com) or on Facebook ( www.facebook.com/brianhodgewriter).

PROTOTYPE copyright © 2010 by Brian Hodge. Originally published 1996 by Bantam Doubleday Dell. Second edition published 2007 by Delirium Books. Macabre Ink digital edition published 2010.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Except for review or discussion purposes, no part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electrical or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the author.

This book is a work of fiction. Characters, incidents, and dialogue are drawn from imagination and are not to be construed as real, or are otherwise used fictionally. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.