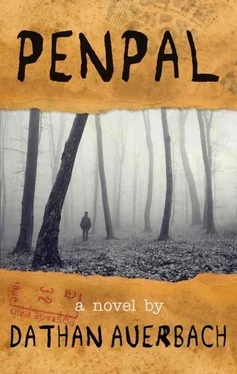

Dathan Auerbach - Penpal

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Dathan Auerbach - Penpal» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: 1000Vultures, Жанр: Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Penpal

- Автор:

- Издательство:1000Vultures

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3.67 / 5. Голосов: 3

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Penpal: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Penpal»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Penpal — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Penpal», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But again, there was no letter at all… just another picture.

This one was more distinguishable, but not fully comprehensible. The camera was sharply angled toward the sky. The photograph caught the top corner of a building in the bottom left of the frame, but the rest of the image was distorted by a lens-flare from the sun. I turned the Polaroid over, but again there was nothing written on the back. My teacher put her hand on my shoulder and said, “A picture’s worth a thousand words, right?” before walking away toward her desk.

“A picture’s worth a thousand words…” I had never heard that said before, and I sat there for a while trying to decide if I believed it.

Because the balloons didn’t travel very far, and because they were all launched on the same day, the board became a bit cluttered fairly quickly. If a letter came in with a picture of a place that wasn’t already overrepresented on the map, it would be displayed, but otherwise the correspondences were distributed to their recipients, so we could take them home as keepsakes of the project. A week or two before the school year ended, the remaining pictures were taken off the map and handed out to their owners. My best friend Josh took home the second highest number of pictures at the end of the year — his penpal was very cooperative and sent him photographs from all around the neighboring city; Josh took home, I think, four Polaroids.

I took home nearly fifty.

The envelopes had all been opened by the teacher, but after a while I had stopped even looking at the pictures. However, the photographs were, if nothing else, a collection, and so I saved them in one of my dresser drawers that housed my other collections. The problem with collections, I had found, was that either there was simply no way to gather all the things in a series because there was no end to it, or there would always be that last item that made your collection incomplete. In my mind, I suppose, the things in the collection weren’t as valuable as the completeness of the collection itself.

My drawer was a mausoleum of my incomplete collections of rocks, baseball cards, comic book cards, and little miniature baseball batting helmets that my mother and I would ceremoniously buy from a vending machine at Winn-Dixie after T-Ball games. I put the photos in a box and slid it next to my baseball cards. With the school year over and summer break just beginning, I turned my attention to other things.

For Christmas, midway through my year of kindergarten, my mom had gotten me a small snow cone machine. It didn’t make very good snow cones, but the fact that I could make them at home now delighted both Josh and me. He came to covet the machine so much that his parents bought him a slightly nicer one for his birthday, toward the end of the school year. The snow cones produced by Josh’s machine were much bigger and were made much faster than when we would use my machine.

Several weeks into the summer break, we decided to take a break from exploring the woods; we would pool our resources and set up a snow cone stand to make money. We thought we would make a fortune selling snow cones at one dollar.

Josh and I lived in different neighborhoods, so we had a conversation about where we would set up shop. As one might have expected, we both wanted to locate the business at our respective houses, so before we even had the cups for the shaved ice, we had our first disagreement.

His neighborhood was a bit nicer than mine, but many of the older houses in my neighborhood had slightly larger yards, and as such, the people who actually cared for them had to be outside for longer amounts of time in order to do so. There were also simply more people in my neighborhood, since there were many houses that stood on fairly small plots of land, and the ongoing construction around where I lived meant that there were always people outside on the weekends.

Josh rebutted by claiming that his neighborhood was nicer than mine was, and this was a thought that had never occurred to me before. I became indignant, and our capacities to engage in a civil and rational discussion became exhausted. Ultimately, I won by trumping all of Josh’s legitimate reasons by exclaiming that it was my idea, and so we would do it at my house.

The first weekend was a disaster. We had both used our machines before, but to be quite honest, we simply weren’t very good snow cone producers. We had two bottles of syrup: cherry and cherry, so there wasn’t to be much variety in terms of flavors. More to our detriment, we had never completely figured out how best to pour the syrup onto the ice, or how much to pour for that matter, so most of our customers had their hands covered in overflowing red dye when they squeezed the paper cups to take their snow cones away. We made about six dollars and stopped for the day.

We didn’t fare much better the second weekend. Josh and I had gotten the hang of the syrup for the most part, but I had the idea that we should use crushed ice in the machines in order to make the snow cones more quickly, since I thought that smaller chunks of ice would shave faster. Instead, the crushed ice became jammed between the blades and the plastic rotor inside the machine and broke my snow cone maker immediately. This machine was one of the nicest things that I owned, and so I became flustered when I couldn’t get it to work.

I took the top off and looked inside. I could see the chunks of ice that were jamming the blades, and so I picked up the plastic case and banged it on the table a few times in an attempt to dislodge them. Looking up, I could see a potential customer coming; I needed to clear the jam quickly. Without thinking, I pushed my hand down into the cavity of the snow cone machine and began carefully wrestling the ice out of the space between the blades and the inside wall. I looked up again, and I recognized the person from the weekend before — forgetting that Josh’s machine was working fine, I turned my attention back to the problem so that I would be ready for our first return customer.

I could feel the ice begin to give and pivot a little as the heat from my fingers melted it. I almost had the problem resolved when I heard Josh say, “Hey, what’s this button do?”

I looked over to Josh and saw that he had his finger on the start button of my machine. Reflexively, I yanked my hand out of my snow cone maker — my middle finger catching the blade on the way out. There was a period of just a few seconds where I thought that I had just scratched myself, but a thin red line soon began to quickly draw itself horizontally along the underside of my finger. I watched as that line widened and spread as blood began dripping from my hand.

I shouted at Josh while he prepared a snow cone on his machine for our anticipated customer, and he said that he was only joking — that he wasn’t really going to push the button. He looked genuinely remorseful from what I could tell, though he seemed to have a problem looking at my hand as he apologized. I think now that Josh had a fear of blood.

Josh had already finished pouring the syrup before the customer got to the table, and he held it gingerly so that it wouldn’t melt. Holding my finger with the opposite hand, I looked around for something to wrap it in. By the time the customer got to our stand, the blood had welled up in the tight fist that I was making around my finger and had begun dripping down my forearm.

As Josh held the snow cone out to the man, I saw our patron’s eyes dart back and forth from the cherry-red ice to my blood-red hand. His expression changed from concern to amusement, and finally he said, “You boys sure have put a lot of yourself into the business!” The man followed this exclamation with a guffaw so long and loud that I could still hear it when I went back into the house to show my mom what I had done to myself. When I got back outside, Josh said that the man had bought the snow cone; we decided to quit while we were ahead, so we packed up and went inside.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Penpal»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Penpal» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Penpal» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.