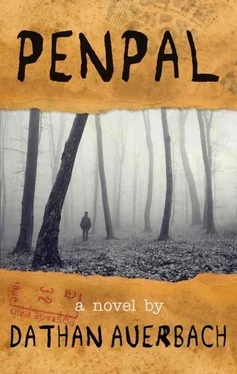

Dathan Auerbach - Penpal

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Dathan Auerbach - Penpal» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: 1000Vultures, Жанр: Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Penpal

- Автор:

- Издательство:1000Vultures

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3.67 / 5. Голосов: 3

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Penpal: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Penpal»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Penpal — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Penpal», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Now begin in the middle, and later learn the beginning; the end will take care of itself.

– Harlan EllisonFootsteps

In a quiet room, if you press your ear against a pillow, you can hear your heartbeat. As a six-year-old boy, the muffled, rhythmic beats sounded like soft footsteps on a carpeted floor, and so as a kid, almost every night — just as I was about to drift off to sleep — I would hear these footsteps, and I would be ripped back to consciousness, terrified.

For my entire childhood, I lived with my mother in a fairly nice, and extremely rural, neighborhood that was in a transitional phase; people of lower economic means were gradually moving in. My mother and I were two of these people.

Those that spend any amount of time driving on interstate highways will see half-houses traveling alongside them. It’s an odd sight if you let yourself think about it; two halves of a house built somewhere miles away from where it becomes a home. Everything about those structures has a feeling of impermanence: the wood that forms them is cut where it isn’t used and assembled where it doesn’t stay; the most permanent things about those houses are the concrete support columns that they rest on, but even those seem transitory in a way. My mother and I lived in one of these houses, but she took good care of it. As a kid, I always thought our house was quite nice.

As I sit here and think about my old home and all the things in it, an amusing and pleasant conflict builds in my mind; I know now that we were poor, but had you asked me then, I would have had no idea what could have prompted that question. My mother must have had so little money to spend, but I never remember her saying the words that tend to become the mantra of some parents when they try to subdue their children’s eager shopping: “we can’t afford it.”

I don’t remember wanting for much; I even had a bunk bed despite being an only child. I’m sure that this is the case for many children in low-income homes, but as a boy, despite the incongruity, I thought my home was as close to a palace as one could hope for. To me, the support columns under the house didn’t represent what the house actually was — an imported structure on a makeshift foundation — but what it could be. I remember asking my mother if we could make the columns taller so our house would tower over all the others.

Part of my love for the house stemmed from my general love for the area surrounding it. The neighborhood itself was relatively large in proportion to the town itself. Small towns lack many of the luxuries of larger towns or cities; what few stores there are close down early, traveling events don’t stop there because they probably missed your small dot on the map, and there aren’t many police or hospitals at your disposal. But, to a kid, these things don’t matter because small towns often provide a luxury that can’t be found in larger, more convenient or populated places: freedom.

Of course, I had rules to follow — I had a lot of them, in fact. But I didn’t notice any of them restricting me because I was allowed to do the one thing a kid in a relatively remote area likes to do — explore. Just a short walk from my back porch was a dense and untamed wilderness that I spent some part of nearly every day surveying. These woods and waterways surrounding the neighborhood were my playground during the day. But at night — as things often do in the mind of child — they would take on a more sinister feeling.

The apparent change in the very nature of the trees and the lake, I think, was mostly my fault. One of my mother’s rules was that I could explore the woods on the condition that I would be home before dark. To motivate my speedy return, I would play games in my mind when leaving the woods at dusk; my feet moved more quickly when I imagined that they were carrying me away from ghouls and beasts. When I would dream, the footsteps would belong to these pursuers.

Sometimes I’d pretend that a hideous and ravenous wolf was charging through the woods just behind me; I’d imagine what would happen if I stumbled or fell and it caught up with me, but when I concentrated too hard on keeping my balance, it would always seem to ensure that I lost it. Other times I’d convince myself that there was an enormous clutter of spiders descending from the trees above and blanketing the earth behind, and that I was always inches away from being ensnared in a collective web or simply overwhelmed by their numbers and tackled by the sheer weight of their individually weightless bodies.

The thing I imagined the most, I think, was that if I didn’t make it home before the sun went down, my mother would be gone — that everyone would be gone, and that I’d be all alone. I always made it back home the quickest when I played that game.

It didn’t take long for these games to become a reflex, and the fear would appear without any effort at all. Some nights I would spill into the house so frantically that it would startle my mother, but this was the winter of the first grade of elementary school, so I tried to compose myself and pretend that I was merely worried about getting home too late.

The things I imagined in the woods just before nightfall created a feeling of general uneasiness in me when the sun retired. My home offered refuge from these terrors, but the architecture of my house came to sabotage my feelings of security. The concrete stilts that raised my house above the earth left a void just below the entirety of the floor of my home. Gradually, my mind came to fill this crawlspace with imaginary monsters and inescapable scenarios, and they would consume my thoughts whenever I was awoken by the footsteps.

I told my mom about the footsteps, and she said that I was just imagining things. This seemed an appropriate accusation given my tactics for making curfew, but I persisted enough that she blasted my ears with water from a turkey baster once just to placate me, since I insisted that it would help. Of course, it didn’t. The footsteps continued that night, but I tried my best to ignore them, just like always.

Despite the general eeriness that the games and footsteps would cast over the nighttime neighborhood, my life was a quiet one. I had adventures by myself, or, more often, with my best friend Josh, but I suppose every kid has their adventures. The only odd or noteworthy events that I can remember happening were the occasions when I would wake up on the bottom bunk despite having gone to sleep on the top. This would only happen every now and again, but it wasn’t really that strange since I’d sometimes get up to use the bathroom or get something to drink and could remember just going back to sleep on the bottom bunk. This would happen frequently enough to remember but infrequently enough to dismiss. In itself, waking up on the bottom bunk never really bothered me.

But one night, toward the end of winter in first grade, I didn’t wake up on the bottom bunk.

I had heard the footsteps, but was too far gone to be woken up by them. When I awoke, it wasn’t from the sound of footsteps, but the feeling of biting cold and violent shivering. As I opened my eyes, the clashing of what I expected to see — what I had nearly always seen when I woke up in a place other than the top bunk — and what I actually saw, frustrated my senses as my mind tried to reconcile my expectations with actuality.

I saw, or rather my mind showed me, the red, cylindrical bars that supported the mattress of the top bunk, but beyond those, I saw stars. Gradually, the bars melted away and faded from my vision, and I was left with only those floating points of light and the jagged, crossing limbs of the tall trees that arched across them high up in the sky.

I was in the woods.

I shouldn’t be here , I thought. The coupling of the woods with darkness was something I had trained myself to avoid.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Penpal»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Penpal» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Penpal» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.