‘We can’t give up on the kid.’

Frost nodded.

‘It won’t hurt to send up a shell at the top of each hour.’

Noble spread a map on the deck. Frost trained her flashlight on the chart.

Miles of beige nothing. Shallow contour lines. Grid squares chequered with the legend: dunes.

‘Hard to get a fix on our exact location. Couldn’t get a clear lensatic reading. Couldn’t raise a soul on the CSEL, either.’

‘Plenty of metal deposits hereabouts,’ said Frost. ‘Iron salts. Manganese. Uranium. All kinds of shit. We’re probably sitting in the middle of some weird electromagnetic anomaly. Won’t clear radio interference until we reach the mountains and climb.’

‘Given our direction of travel, given that we were about six or seven minutes from the drop point, I’d say we were here.’

He circled a central section of wilderness.

‘That’s a long fucking walk,’ said Frost. ‘A shitload of desert any direction you care to choose. On foot? Person couldn’t last more than a couple of days in this kind of environment.’

‘It would have to be our very last resort. But hey. There’s always the chance Trenchman will show up at first light. Long shot. But he might have spent the day fixing a fault with their Chinook, trying to get it back in the air. Can’t rule it out. This time tomorrow we could be feet-up in Vegas sipping a cold one.’

‘Perhaps,’ said Frost. ‘But I’d feel a whole lot better if we got power to the flight deck and actually raised someone on the damned radio.’

The upper cabin.

Frost sat in the pilot seat and cycled the AC selector.

Noble, from below:

‘Anything?’

She tapped a volt gauge. The needle remained unresponsive.

‘Total flatline.’

The lower cabin.

Noble helped Frost lift a fuse panel from the wall behind the EWO console. The primary distribution bus. He held the flashlight steady while she examined tangled cable.

Burnouts. They trimmed and spliced cable.

They replaced the fuse panel. All load switches set to green. She returned to the pilot seat and toggled for power.

Nothing.

‘We should be getting twenty-eight volts DC from the auxiliaries. Enough to restore essential systems.’

‘Line break?’

Frost shook her head.

‘Cells must have shorted out, drained dry.’

‘Dammit.’

‘We’ve got one more shot,’ said Frost. ‘There is a backup power cell, a nickel-cadmium battery in the aft of the plane.’

‘Yeah?’

‘So I guess someone will have to take a walk and find the tail.’

Noble and Hancock looked out over the moonlit dunescape.

A wide debris trench, like preliminary construction for a highway. The trench was littered with wreckage. Structural spars, scraps of fuselage, a massive undercarriage bogie ripped from a wheel-well.

‘Can’t be too far,’ said Hancock.

They set off.

Noble looked towards the horizon. Pinnacles and flat-top mesas, a jagged ribbon of black against a fabulous dusting of stars.

‘Funny. You can make out the mountains clearer than day.’

Hancock stumbled a couple of times.

‘You all right?’ asked Noble.

‘Concussion.’

‘Maybe you should sit this one out.’

‘It’ll pass.’

‘How much ground you reckon we’ve covered?’ asked Noble.

‘Quarter of a mile, give or take.’

‘Can’t be too far.’

‘Better watch where you tread,’ said Hancock, stepping over a torn wing panel. ‘This shit wants to cut you wide open. Like walking through a field of razors.’

‘Think we’re the first humans to set foot on this patch of ground? Sure, plenty of people criss-crossed the desert. Pioneers. Prospectors. But this particular stretch of sand. Think we’re the first?’

‘Pretty good chance we’ll be the last.’

They kept walking.

Their breath fogged the air.

‘Freezing.’

‘Enjoy it,’ said Noble. ‘Sunrise in a while. Another hot day.’

‘Shame about Early.’

‘Let’s not write him off just yet. He’s green, but he’s not stupid.’

‘You and Frost are pretty tight, yeah?’ asked Hancock.

‘The whole crew. Been flying a long while. Four, five years.’

The tail section sat in the middle of the debris trench a quarter of a mile from the main fuselage. A massive cruciform silhouette against the stars.

They trudged towards the wreckage until they were within the moon-shadow of the stabiliser fins.

Tail number: MT66.

The sand was carpeted with fluttering foil strips spilt by the underwing chaff dispensers.

The orange brake chute was spread on sand behind the empennage. Fabric wafted and rippled.

The rudder gently creaked and swung in the night breeze.

They kicked through foil.

Noble banged his fist on the fuselage. Hollow gong.

‘Early? Yo. Nick. You in there?’

No reply.

Hancock looked around.

‘No footprints, that I can see. Nobody here but us.’

They peered into the cave-dark of the fuselage interior. The flashlight beam played over twisted spars and ripped fuselage panels.

A tight crawlspace.

‘Think there might be snakes? Scorpions?’ asked Noble.

‘Not this deep in the desert. Nothing can survive out here.’

They climbed inside.

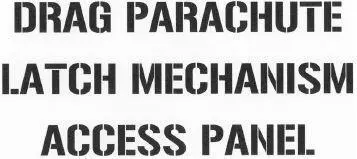

The tail section of the plane had been designed to house four 20mm Vulcan cannons remote-operated by a gunner stationed on the flight deck. The quad weapon and feed chutes had long since been removed and the gun ports welded shut. The compartment was now home to a rack of electronic countermeasure gear. Ammo drums replaced by a radome and omnirange antennas. Access via a crawlway that ran the length of the plane from the crew cabin, through the bomb bay, to the rear.

Hancock shuffled along a short section of access tunnel on his hands and knees. Sheet metal slick with hydraulic fluid. Dancing flashlight beam.

Noble squeezed into the tight compartment. They crouched shoulder-to-shoulder, ignoring each other’s body odour.

The flight recorder. Mission data housed in a steel cylinder:

FINDER’S INSTRUCTIONS – US GOVERNMENT PROPERTY. IF FOUND PLEASE RETURN TO THE NEAREST US GOVERNMENT OFFICE.

The UHF beacon. A winking green light confirmed the beacon was active, operating on internal power, broadcasting a homing signal on SAR.

‘How long will she transmit?’ asked Hancock.

‘Four weeks, give or take.’

The backup cell. Twice the size of an automobile battery.

CAUTION – SHOCK HAZARD.

‘Is that it?’ asked Noble.

‘Yeah.’

He disconnected the terminals.

‘Watch yourself.’

They unscrewed hex bolts and jerked the unit from its rack.

Noble constructed a sledge from a section of deck plate. He cut a length of power cable and lashed it as tow rope.

Hancock watched him work.

‘Feel like an idiot. Sitting here while you break sweat.’

‘Best kick back awhile. Take it easy.’

‘Head keeps spinning. Can’t hardly see straight.’

‘You need rest. No use pretending otherwise. Normal circumstances, a head wound that bad would have you laid up in ICU a long while. CAT scans, the works. Weeks before the nurses let you throw back the sheet and put your feet on the floor. Soon as we get back to the plane, you ought to shoot some morphine. Pop a couple of Motrins, at least. You need to recuperate.’

‘Fuck that shit.’

‘You got to be dispassionate. Set the macho bullshit aside. Your body is equipment in need of repair. Treat it as such.’

Читать дальше