I drove through the night and I drove through the dawn, coming in from the west with the sun in my eyes. I left the car on the side of the paved road in place of the first car I had stolen, then walked the rest of the way up the paved road, down the gravel road, down the dirt road. The house looked just as I had left it, and I banged my way through the screen door and inside, calling her name, receiving no response.

The house was still, the floors and furniture dim with dust, and I wandered from room to room, confused. Finally I went out the back door and into the meadow.

I could instantly see her there, sitting just as I had left her, and I started quickly toward her, calling her name again.

But once I came a little farther I found myself slowing, stopping. For I could see that what I had thought was her arm was only the bones that had once structured the arm, the flesh mostly gone. And I saw that a part of her on the other side, too, was in the process of grimly disarticulating itself with the aid of vermin and time, and I remembered what, out of love or hate, had happened, and why I had left in the first place.

And then what choice was there but to turn about in my dead man’s clothes and leave, to go through the house and out the front door and get into the car again, to set off again, to fling myself free of her gravitation and, this time, never, never come back?

Dread,

illustrated by Zak Sally

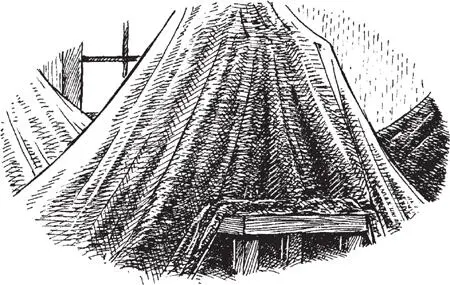

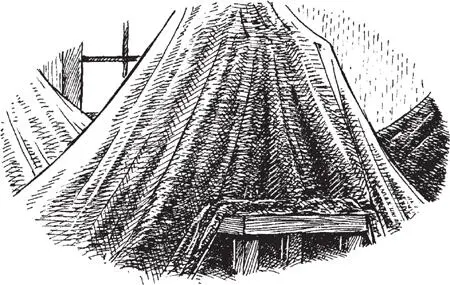

In the late afternoons, after school, in the days just after their father had left their mother, the two girls would strip all the blankets off their beds. Gathering them up as best they could, they carried them out of their rooms and down the narrow hall to drop them in a heap in the living room. They tucked blanket edges under couch cushions or put them on furniture with encyclopedias piled on them, and then stretched the blankets from couch to chair or from chair to window ledge. When done, they had a series of tents, all overlapping, the living room become a series of billows and dips under which they could crouch.

For several months they lived each afternoon under these tents, light coming mottled through the fabric. They felt good there. Sometimes they read or drew or talked there, other times just sat. When their mother came home from work, she often knelt down and asked how they were doing, and what. The youngest girl mostly half-shrugged and said fine, they were doing fine. The oldest girl never answered unless she had to, unless the mother addressed her directly and more than once. It was not that she disliked her mother, only that she thought it was none of the mother’s business. The tents had been the oldest girl’s idea; she had made them so as to have a substitute house within the larger house, for now that the father was gone the house no longer felt like it was her house. It was only in the tents that she began to feel at home again. In the tents it was the two of them, the two girls, alone but together, and nothing changing unless they wanted it to. So when the mother knelt down to ask what they were doing in the tents, the oldest girl didn’t feel she should have to answer: the tents were not about the mother.

When the father had left, it was as if he had taken part of the house with him. It no longer felt like the oldest girl’s house, but neither did it feel like her house at the apartment the father rented across town. Every other week the girls’ father showed up, looking somewhat disoriented, to take them away to his apartment, where they stayed for almost two full days, the father trying to keep them entertained until the mother arrived on Sunday afternoon to take them to church. At the father’s house, in his apartment, the girls slept on the front-room floor in sleeping bags. This practice the father sometimes referred to as camping, which made the oldest girl try to imagine she was out in the open, under the stars. But still she never felt at home in a sleeping bag like she did in the tents.

One problem with the father’s new house was that there were not enough blankets to make a good tent. The father was what the mother called a cold sleeper; he had only one blanket in his apartment and usually slept (so the oldest girl had found sometimes late at night when she couldn’t sleep and went to the father’s bedroom to see if the father was asleep himself) on the edge of the bed, half his body uncovered, the blanket splitting him in two. During the day, the girls were allowed to take this single blanket from the bed and stretch it from the back of the couch to the bookshelves behind, then tuck it in tightly between the books, but one blanket was not enough; it made a tunnel but hardly a tent. They had tried, the two girls, unzipping the sleeping bags to use them as blankets to make tents, but the sleeping-bag fabric was heavy and thick — light didn’t come through in the way it did with a good blanket. And in any case, the father didn’t have enough furniture to make good tents. All he had was a couch and a chair. Now that he was out of the house, the father didn’t have much of anything. In the kitchen, all he had of utensils were three of each: three knives, three forks, three spoons, all taken from the larger collection of wedding flatware that still resided with the mother. If he and the girls ate anything, the father would have to wash utensils before they could eat again.

The father, when he was feeling exuberant, when he was at his best, would claim that they were lucky girls, that most little girls did not have two houses like they did. But the oldest girl felt that no, they did not now have two houses: they were between houses and thus in a way had no house. And it was clear to the oldest girl that their father did not feel at home in his new house, that in a way he had no home of his own either. Unlike the father, the oldest girl at least had the tents to go to, and after school, each day, she and her sister would make the tents and lie beneath in the warm space, watching the mottled light filter through.

Near the end of his fourth month out of the house, the father began to let them down. He still showed up on Friday to take them to his house, to his apartment, but they never could count on when. Before, he had always been sitting on the porch when they came home from school, but now it was hard to say. Sometimes he was there, waiting, but most days he would not show up until the mother was long home from work and it had begun to grow dark outside. A few times the mother got tired of waiting and called him, and when he showed up ten minutes later he was shamefaced and apologetic.

The oldest girl knew something was going wrong with the father, but could not say what exactly. She knew he was distracted but could not say why. In a way, what or why did not matter. The youngest girl, too, felt something going wrong with the father, and the youngest girl was nervous about him. The youngest girl was, so the mother always said, high-strung, and thus needed from time to time to be soothed and calmed down. The oldest girl always tried to calm her down. She did not always notice things as quickly as the oldest girl did, but when she did notice them she seemed to feel them more, and since the father had left, it had somehow become the oldest girl’s job to help calm her down. Because of that, the oldest girl had learned not to show when she knew something or felt it, so that sometimes she felt like she was just watching things happening but nothing really was ever happening to her. The oldest girl thus had learned to cope with everything alone and quickly, so that by the time the youngest girl began to catch wind of things she could be there, as calm and placid as glass, to comfort her.

Читать дальше