Ellen Datlow - The Beastly Bride

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ellen Datlow - The Beastly Bride» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Penguin Group US, Жанр: Ужасы и Мистика, Фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

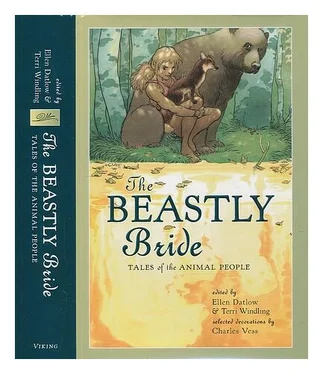

- Название:The Beastly Bride

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Group US

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-101-18617-6

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Beastly Bride: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Beastly Bride»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Beastly Bride — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Beastly Bride», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

If it hadn’t been for football, I would have been an outsider in high school, angry and fucked-up, a loner whom everyone would have voted the Most Likely to Go Columbine. People said I took after my mama — I had her prominent cheekbones and straight black hair and hazel eyes. She was one-quarter Cherokee, still a beauty as she entered her forties, and she had a clever mind and a sharp tongue that could slice you down to size in no time flat. She was a lot quicker than my daddy (a stoic, uncommunicative sort), way too quick to be stuck in a backwater like Edenburg. Some nights she drank too much and Daddy would have to help her upstairs, and some afternoons she went out alone and didn’t return until I was in bed, and I would hear them fighting, arguments in which she always got the last word. When I was in the eighth grade I discovered that she had a reputation. According to gossip, she was often seen in the bars and had slept with half the men in Taunton. I got into a bunch of school-yard fights that usually were started by a comment about her. I felt betrayed, and for a while we didn’t have much of a relationship. Then Daddy sat me down and we had a talk, the only real talk we’d had to that point.

“I knew what I was getting when I married your mama,” he said. “She’s got a wild streak in her, and sometimes it’s bound to come out.”

“People laughing behind your back and calling her a slag. how do you put up with that?”

“Because she loves us,” he said. “She loves us more than anyone. People are gonna say what they gonna say. Your mama’s had a few flings, and it hurts — don’t get me wrong. But she has to put up with me and with the town, so it all evens out. She don’t belong in Edenburg. These women around here don’t have nothing to offer her, talking about county fairs and recipes. You’re the only person she can talk to, and that’s because she raised you to be her friend. The two of you can gab about books and art, stuff that goes right over my head. Now with you giving her the cold shoulder, she’s got no outlet for that side of things.”

I asked straight out if he had slept with other women, and he told me there was a time he did, but that was just vengeful behavior.

“I never wanted anybody but your mama,” he said solemnly, as if taking a vow. “She’s the only woman I ever gave a damn about. Took me a while to realize it, is all.”

I didn’t entirely understand him and kept on fighting until he pushed me into football at the beginning of the ninth grade; though it didn’t help me understand any better, the game provided a release for my aggression, and things gradually got easier between me and Mama.

By our senior year, Doyle and I were the best players on the team and football had become for me both a means of attracting girls and a way of distracting attention from the fact that I read poetry for fun and effortlessly received As, while the majority of my class watched American Idol and struggled with the concepts of basic algebra. My gangly frame had filled out, and I was a better than adequate wide receiver. Not good enough for college ball, probably not good enough to start for Taunton, but I didn’t care about that. I loved the feeling of leaping high, the ball settling into my hands, while faceless midgets clawed ineffectually at it, and then breaking free, running along the sideline — it didn’t happen all that often, yet when it did, it was the closest thing I knew to satori.

Doyle was undersized, but he was fast and a vicious tackler. Several colleges had shown interest in him, including the University of South Carolina. Steve Spurrier, the Old Ball Coach himself, had attended one of our games and shook Doyle’s hand afterward, saying he was going to keep an eye on him. For his part, Doyle wasn’t sure he wanted to go to college.

When he told me this, I said, “Are you insane?”

He shot me a bitter glance but said nothing.

“Damn, Doyle!” I said. “You got a chance to play in the SEC and you’re going to turn it down? Football’s your way out of this shithole.”

“I ain’t never getting out of here.”

He said this so matter-of-factly, for a moment I believed him; but I told him he was the best corner in our conference and to stop talking shit.

“You don’t know your ass!” He chested me, his face cinched into a scowl. “You think you do. You think all those books you read make you smart, but you don’t have a clue.”

I thought he was going to start throwing, but instead he walked away, shoulders hunched, head down, and his hands shoved in the pockets of his letterman’s jacket. The next day he was back to normal, grinning and offering sarcastic comments.

Doyle was a moody kid. He was ashamed of his family — everyone in town looked down on them, and whenever I went to pick him up I’d find him waiting at the end of the driveway, as if hoping I wouldn’t notice the meager particulars of his life: a dilapidated house with a tar paper roof; a pack of dogs running free across the untended property; one or another of his sisters pregnant by persons unknown; an old man whose breath reeked of fortified wine. I assumed that his defeatist attitude reflected this circumstance, but I didn’t realize how deep it cut, how important trivial victories were to him.

The big news in Culliver County that fall had to do with the disappearance of a three-week-old infant, Sally Carlysle. The police arrested the mother, Amy, for murder because the story she told made no sense — she claimed that grackles had carried off her child while she was hanging out the wash to dry, but she had also been reported as having said that she hadn’t wanted the baby. People shook their heads and blamed post-partum depression and said things like Amy had always been flighty and she should never have had kids in the first place and weren’t her two older kids lucky to survive? I saw her picture in the paper — a drab, pudgy little woman, handcuffed and shackled — but I couldn’t recall ever having seen her before, even though she lived a couple of miles outside of town.

During the following week, grackle stories of another sort surfaced. A Crescent Creek man told of seeing an enormous flock crossing the morning sky, taking four or five minutes to pass overhead; three teenage girls said grackles had surrounded their car, blanketing it so thickly that they’d been forced to use a flashlight to see each other.

There were other stories put forward by more unreliable witnesses, the most spectacular and unreliable of them being the testimony of a drunk who’d been sleeping it off in a ditch near Edenburg. He passed out near an old roofless barn, and when he woke, he discovered the barn had miraculously acquired a roof of shiny black shingles. As he scratched his head over this development, the roof disintegrated and went flapping up, separating into thousands upon thousands of black birds, with more coming all the time — the entire volume of the barn must have been filled with them, he said. They formed into a column, thick and dark as a tornado, that ascended into the sky and vanished. The farmer who owned the property testified to finding dozens of dead birds inside the barn, and some appeared to have been crushed; but he sneered at the notion that thousands of grackles had been packed into it. This made me think of the sofa at Warnoch’s Pond, but I dismissed what I had seen as the product of too much beer and dope. Other people, however, continued to speculate.

In our corner of South Carolina, grackles were called the Devil’s Bird, and not simply because they were nest robbers. They were large birds, about a foot long, with glossy purplish black feathers, lemon-colored eyes, and cruel beaks, and were often mistaken at a distance for crows. A mighty flock was rumored to shelter on one of the Barrier Islands, biding their time until called to do the devil’s bidding, and it was said that they had been attracted to the region by Blackbeard and his pirates. According to the legend, Blackbeard himself, Satan’s earthly emissary, had controlled the flock, and when he died, they had been each infused with a scrap of his immortal spirit and thus embodied in diluted form his malicious ways. No longer under his direction, the mischief they did was erratic, appearing to follow no rational pattern of cause and effect.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Beastly Bride»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Beastly Bride» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Beastly Bride» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.