“She said she wanted to go someplace that smelled like flowers,” he said. “To have her accoutrement removed and forget everything that happened to her here. And, and she wanted you to go too. She said she was afraid for you.”

Elena cradled the revolver-cuff, crouched in the whispering frozen reeds of the marshes.

Could she cross the border from Russia into a new life of dried roses and Sunday promenades, after letting some physician remove her tail and opera glasses? Could she forget that she had once had a mother and a father and a sister, forget that monsters had taken them from her, forget that a monster had grown inside her too?

Could she ever allow it all to fade away?

That’s what Nina would have wanted.

But she felt her tail flex, feathers grinding on feathers, and she knew: something had broken inside of her forever, no matter if she never saw Russia again.

“Elena, please, she would have wanted—”

“My tail is just as much a part of me as her lungs were.” Elena leapt up, on her tiptoes, looming above him so he shrank away.

She slapped the revolver-cuff over her left wrist. She clenched her teeth as the metal rods curled over her forearm, scraping off her arm hair and digging in, reaching down to her bone. The wood settled against her skin and the trigger fitted into place just above her wrist-bone.

She shouldered around Aleksandr and marched towards the boxcar. She pushed inside, tore Nina’s shawls off her bunk, rummaged through the carpetbag and pulled out Father’s book of maps of Novgorod. She marked corners of the marshes where she could hide with her revolver-cuff and ambush soldiers, parts of the kremlin wall where she could throw homemade explosives, anywhere she could go to destroy the people who had killed Mother, Father, Nina, who had taken away everything, who had created the dark avenging firebird that could never stop fighting.

The Little Begum

Indrapramit Das

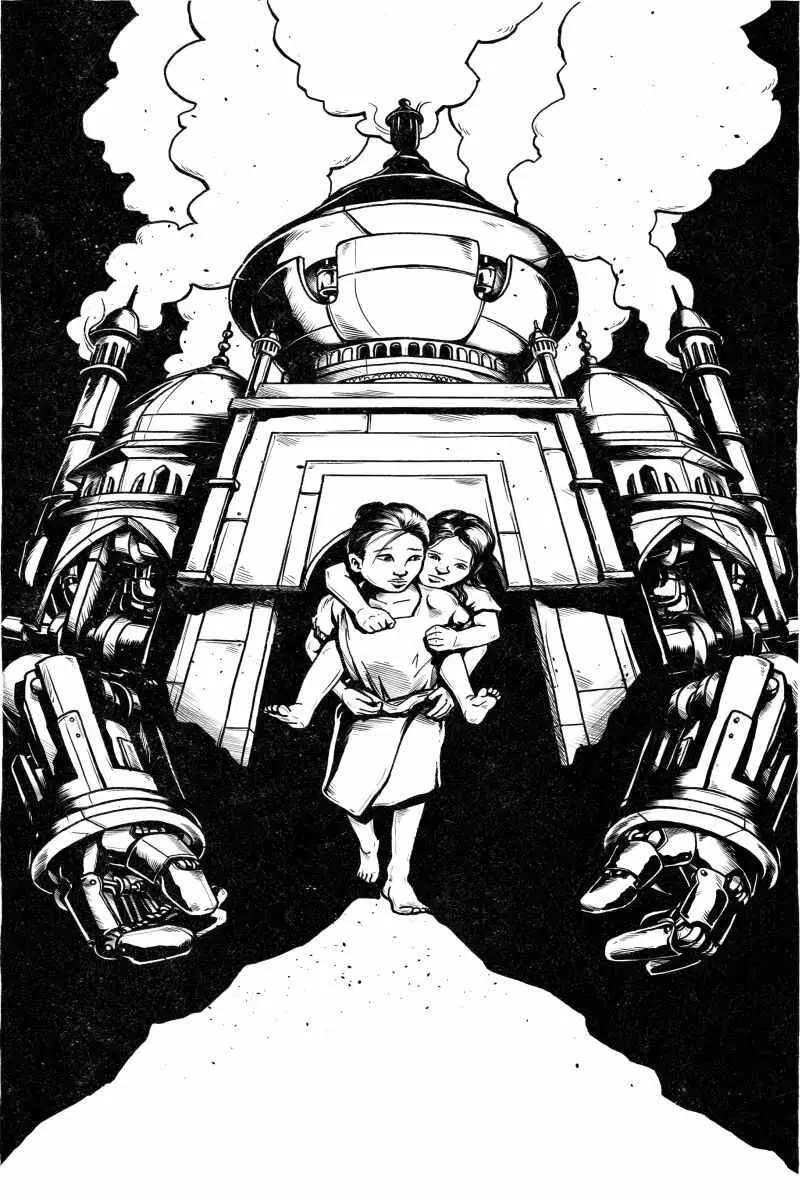

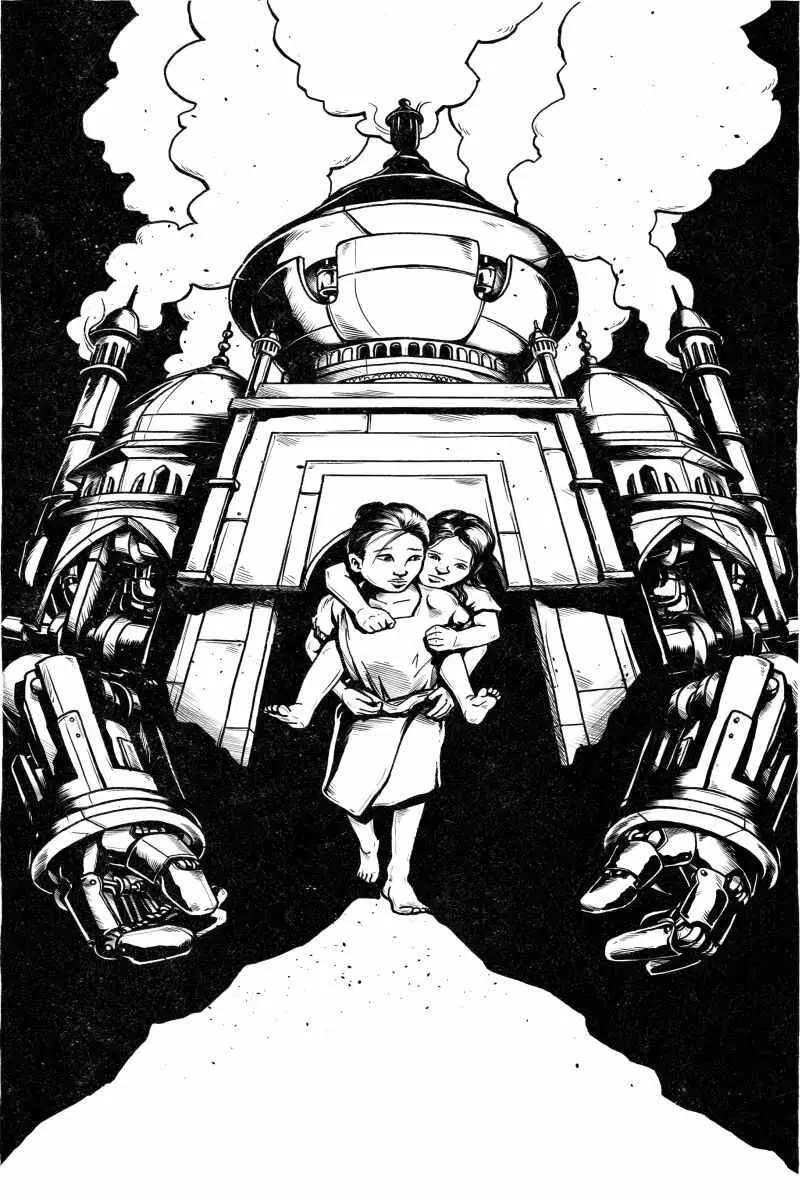

Bina looked at the metal bones covering her worn and stunted limbs, cold against her legs and feet, lovingly layering the scars of her disease. These new hands and feet were heavy, lead and steel woven with leather straps onto the outside of her body. She had watched her sister Rani make them with fire and scrap, bending the pieces with hammer and heat, her second-hand British goggles flickering with the light of the workshop’s tiny forge, sparks flying off her skin as if she were invincible. Bina did not feel invincible wearing them, these skeletal gloves and boots. They trapped her already strength-less arms and legs, weighed them down till she felt more helpless that she’d ever been, especially with Rani standing over her, ten years older, so much life in her limbs.

“When the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan’s dearest wife Mumtaz died giving birth to their fourteenth child, his grief was so all-consuming he could barely think, let alone rule an empire. So he decided he would build a monument to his grief, to honour the woman who had been so important to him.”

“The Taj Mahal!” said Bina. She knew some history from her time in the boarding houses, and the stories Rani told her. She let Rani go on.

“That’s right. Shah Jahan gathered the best craftsmen, the best metalworkers,”

“Like you!” said Bina. Rani smiled and nodded.

“…and the best engineers in his realm, and they built a monument, a metal being to house and guard his wife’s body. The Taj Mahal was the greatest automaton ever built—over 300 feet tall, plated in ivory, its massive limbs inlaid with lapiz lazuli and onyx and other precious stones, its contours cleverly crafted to look like a palatial tomb when it crouched at rest like a man folded on his knees with his head to Mecca, the spiked tanks on its back raised to the sky like graceful white minarets. To look upon the Taj Mahal walking along the banks of the Yamuna and across the water lapping its metal ankles as if the broad river were a little stream, was to see the impossible.

And that’s because it was impossible. That metal and ivory giant couldn’t walk, not even with the most powerful and intricate steam engines and hydraulics built by the empire’s best engineers. It would topple and crash before taking a single step. No, it needed a pilot who had the gift of telekinetic thought, to lift its every component, to give it a human soul to go along with the machinery.”

Like me , Bina didn’t say. She realized why her sister was telling her this story.

“Shah Jahan tried piloting it himself. He failed. Very few, after all, are born with the talent of telekinesis, a truth the Emperor did not learn easily. But he did learn it eventually. After scouring the Empire with recruiters, he found, perhaps aptly, that Gauharara Begum, the final daughter Mumtaz had left him with, was the one he was looking for, when one day she lifted an elephant into the air and gently put it down just by looking at it. She was eight at the time, like you. So with teary eyes Shah Jahan asked his little daughter Gauharara if she would pilot the walking palace that guarded her mother’s remains within its chest. Gauharara said that she would be honoured.”

“And so she did. She was carried by the Emperor’s guards through the winding tunnels of the vast being, past its engines and gears and pipes, past the chamber in its heart that held Gauharara’s mother, past its tanks, and she was placed in its head, in a soft cavern of quilted walls. The little Begum made the Taj Mahal walk, looking out of its filigreed eyes to the empire her father ruled, once with the help of her mother. Gauharara Begum took the huge metal and ivory beast across the land, with the aid of a faithful crew that ran its engines. The Empire celebrated this wonder amongst them striding in the distance, colourful pennants like hair lashing behind it, breathing steam.

But before long Shah Jahan’s third son, Aurangzeb, ordered that the giant never be piloted again, because it was blasphemous to create such automatons, that this lifeless walking idol was a mockery of Allah. Aurangzeb had his father and his beloved Gauharara put under house arrest at the Red Fort in Agra, and after a war of succession with his brothers, became the next Mughal Emperor in a sweeping victory. Shah Jahan died imprisoned, and Gauharara died many years later of old age. Aurangzeb was a devout, efficient Emperor, but oversaw the last years of the Mughal Empire that was. The Emperors that followed led it to its decline, and eventually, they were easily defeated by the British Empire with their airships and tanks. Perhaps if the Mughals had made more automatons to rid the Taj of its solitude, and kept them walking, they’d have kept this land too. They could have thrown airships from the sky, and crushed tanks under their feet. The Taj Mahal never walked again, folding into its rest by the banks of the Yamuna, where to this day its empty tanks gleam like minarets on the horizon, its scalp and shoulders shorn of pennants.”

Bina nodded, looking straight at her sister’s grease and oil covered face glimmering in the candlelight, at her coarse tattooed hands between her knees. She smiled. Somewhere in the slum, a stray dog barked.

“I know why you told me that story,” Bina said. She wondered if their mother or their father had taught Rani to tell that story. Or both.

“Of course you do. You’re a clever girl,” Rani said.

“You told it really well. But it’s just really sad,” Bina murmured.

“One day,” her sister said, putting her warm palm on Bina’s cheek. “You’re going to see the Taj Mahal at rest by the banks of the Yamuna. You’re going to walk, walk with me, and we’ll get out of here and go north to see it. Understand?”

Читать дальше