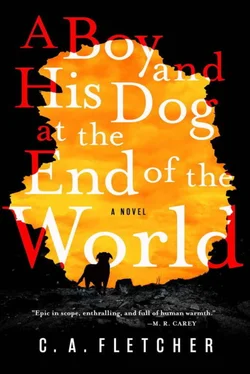

C Fletcher - A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «C Fletcher - A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2019, ISBN: 2019, Издательство: Orbit, Жанр: sf_postapocalyptic, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World

- Автор:

- Издательство:Orbit

- Жанр:

- Год:2019

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-316-44945-8

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

And now they are all gone, I thought, and then found Brand looking at me as though he was reading my thoughts. He nodded.

The last wave, the Busters, broke, he said. And this is the New Dark Age. Maybe, probably, the Last Dark Age. Then he smiled broadly, as if to break the solemnness that had taken over from the holiday mood.

You wanted to know what a hot country’s like? he said to Bar. I can show you.

He reached into the bag again, and this time didn’t have to rummage too much. He came out with a squat glass jar of something as tawny and red as his hair. I could see it was a jelly and not another liquid, like the Akvavit, because as he tilted it the darker strips of whatever was suspended in it didn’t move. It reminded me of the single amber bead Mum has round her neck, the one with a bit of insect trapped in it. Backlit by the flames in the grate, it looked like someone had reached into the sky and taken a lump out of a setting sun and bottled it.

Is it jam? said Bar.

Sort of—but not, he said. It’s marmalade.

Like the cat? said Bar, looking at me. Like the one in the book?

Bar used to read us a picture book about a marmalade cat. It was Joy’s favourite when we were small—that and a book called D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths —and it was so loved it fell to bits and had to be held together by an old bulldog clip. I don’t know what happened to it. Maybe someone hid it so as not to be reminded of Joy. I hadn’t thought about it for years. The memory of it tugged something inside me and made my eyes sting.

Bet you never tasted it, said Brand. Marmalade.

It’s made of oranges, said Bar, chin tilting up, keen to show she knew stuff.

Ever tasted an orange? he said, looking round at us all.

We shook our heads.

Warmer up here than it used to be, said Dad, but still not warm enough for citrus.

Citrus. Dad didn’t like people thinking he didn’t know stuff either.

Brand unsnapped the lid and held it out.

This is what a hot country is like, he said. Fill your noses first.

We all leaned in and inhaled. It was something I’d never smelled before: clean yet spicy. It had a tang, a cut to it, and yet it was also, in some way I then thought was a miracle, sunny.

You have bread and butter, he said. We will have marmalade sandwiches as a dessert. A treat. As thanks for your hospitality.

And then he smiled, wide and white in the dense red of his beard, and waggled his eyebrows as if the whole world was a fine joke and we all lucky to be in on it together.

And to sweeten you up, because tomorrow I will take you to my boat and show you the converter and then try and make you give me much too much fish and food in trade for it. I may even see if you’ll let me have that fine bitch there.

Bar snorted.

Over Griz’s dead body, she said, matching his smile.

Oh, it won’t come to that, he said. Was just a thought. She is a very fetching dog though.

We’ll find something to trade it for—if it is the right converter, said Dad, and it came to me that the edge in his voice was because he was not quite liking the fact they were smiling at each other.

Your friends on Lewis said it was, Brand said. But you will see for yourself. Tomorrow.

The bread was cut, a smear of butter laid on each piece, and then Brand spread a thick layer of orange jelly on them.

What are the bits? said Bar.

The peel, he said. I cut it myself. I made it according to an old recipe book. I made it when I was in Spain, where there were no people but too many oranges. I found sugar in a ruined hotel and used that. It’s sweet and yet sour. Even if you don’t like it, you’ll know what the south is like when you taste it.

The taste was shockingly intense, rich and more complicated than anything I had ever eaten. As he had said, it was sharp and yet sweet, but not sweet in the way of honey: it was an intensity that seemed to fill the whole mouth, but I could not taste the sun in it because the sweetness caught on the tooth the ram had chipped, and sent a lance of pain into my jaw.

It felt like the mouthful had bitten me, and though I winced no one saw me because they were all enjoying this new treat in their own ways. Bar was laughing; Dad had his eyes closed as if shutting out the world was making the experience all the more powerful. Brand was looking at my mother.

I folded the bread over on itself and palmed the sandwich.

Amazing, said Bar. It’s like a mouthful of summer.

Tastes like it smells, said Dad. Thank you. It’s wonderful.

Better than the firewater, I said because everyone seemed to be expected to say something.

More, have more, said Brand, reaching for the bread. Once you have opened the jar the taste goes very quickly. It will taste of slop tomorrow. We must enjoy it while the magic is still in it!

I excused myself, saying now I too needed a piss. Ferg was in the darkness outside, where he had been listening, and before he could ask I handed him the sandwich. He grinned and punched me on the arm, which was his way of showing affection.

Then we walked behind the house and he ate it. I watched his face as he did so, and saw the happiness it gave him.

It does taste of sunlight, he whispered. It’s wonderful.

It hurts my tooth, I said. I’ll sneak you more when I can, or hide it till he goes to sleep. He says he always sleeps on his boat.

Hope he’s tired, said Ferg, pulling his coat tight round himself. Because I’m getting cold out here.

Don’t know if Dad trusts him yet, I said.

That’s Dad being Dad, he said. But that’s okay. You go back in before he wonders where you’ve gone.

When I returned, Brand was talking to Dad about the converter, and Dad was smiling and yawning and saying tomorrow was soon enough to talk trade. Bar was chewing her way through her second sandwich, and Mum had fallen asleep.

Bar and I cleared the table and I pocketed the sandwich they had left me. Bar saw and silently nodded. She knew I was saving it for Ferg. She did not know I had not eaten mine because of the tooth pain.

Dad yawned again and said it was time to sleep, and began to take Mum to their bedroom, shaking her awake and leading her ahead of him. He told Brand he was welcome to sleep ashore, but Brand said he’d stay and chat with Bar and me and then sleep on his boat, as was his habit.

Bar was also yawning by this time, and as Brand and I talked further about the books I liked and the ones he had read, her head dropped and she went to sleep at the table beside me. I carried on talking, and now I know one of the reasons was because I was enjoying this new friendship, a new friend being something every bit as exotic to me as the marmalade was for the others.

As we talked, Brand ruffled Jess’s hair, scratching behind her ears. She leant into him as he did so. I felt another tug inside me, but dogs are open-hearted and it doesn’t do to be jealous of an animal’s affections, so I pushed the feeling away and started laying out the bowls for breakfast. I can’t remember exactly which books we talked about, and the talking went on for a while, almost as if we were each waiting for the other to admit they were tired, but neither wanting to be the first to say it. I do remember talking about a line in another book called The Death of Grass that perturbed me. It wasn’t in the later part of the story where society fell apart and people began killing and raping and turning back into something feral. It was in the early bit of the story, before the grass and the wheat and the crops started dying and the famine began. It was a simple line, something like “the children came home from half term and they drove to the sea for a holiday”. It was so different from my After world, that Before world where children were sent away from their home to go to a school. All the learning I had, and there was a lot because Dad’s Leibowitzing meant he insisted we filled our minds with what might be useful and shouldn’t be lost, happened in or in sight of my home. And going to the sea for a holiday? I’ve never been out of sight of the sea, not for a whole day. I don’t know what that would be like. Sea’s in my blood. Brand nodded and reached over and bumped fists with me. I told him I didn’t know how easy I’d breathe if there was not at least some water glinting on the horizon.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.