He burned her hand, I choked.

No, said Brand. She said no. And she said that she wasn’t frightened of him. He said he’d see about that, and he put the red poker in front of her face and asked if she was still so brave and…

His voice trailed off.

And? I said. And what?

And she was, said Brand. She just grabbed the hot end and pushed it right back into his face. So her hand is puckered and pulled out of shape by the burn scar, and he nearly lost an eye, and carries her mark across his cheek beneath that mask.

Good for her, I said.

Yes, he said. Good for her. Tough little nugget. No doubt she’s your sister. Looks like you too.

That’s why I first cut my hair short at the back and sides, like a boy. Because even when Mum was at her worst she’d see me and get distressed, thinking I was Joy come back. I thought Dad would be angry with me for hacking off my pigtails, but he wasn’t. He said it looked good and even tidied it up for me. Now I think maybe he also wanted me to look like a boy in case they came back, looking for more young girls to steal. I don’t know. I just like my hair like this. Out of the way, no fuss when you’re in the wind, working.

I do know that’s why he introduced me as a boy to Brand. For my own protection. It was a warning, even then. Do not trust this stranger. Any strangers, really. That’s why I went along with the lie with John Dark. Dad’s always been overprotective about me, but somehow in his eyes Bar’s always been big enough to look after herself. He’s not used to the fact I grew up and am just as tough as her now.

Was it always safer being a boy than a girl, even when you were alive?

I thought about what else Joy had said.

Do you think they sold her? I said. My parents?

His eyes went away from the Judas hole. I heard his body slide down the door into a sitting position, leaning back against the metal.

Do you? he said.

Not for a minute, I said. Not for a minute.

For a tithe, he said. Would they have paid her as a tithe?

You mean because of what she said? I said. So they’d leave the rest of us alone?

Yes, he said. Would your father have done it?

I didn’t have to think.

No, I said.

Because you’re so sure he’s a good man? he said.

No, I said. Because he’s not soft.

No, he said after a bit. No. He didn’t seem to be.

He isn’t, I said. Any more than I am.

Or I, said Brand.

We’re not the same, I said. You’re not the same as us.

Maybe, he said. But we’re all from the north. Things are harder there. And soft doesn’t get much done.

He was like that, Brand. He always said one thing too much. He liked the sound of his voice I think. So he would overspeak and get braggarty—and then you trusted him less than if he hadn’t gone on.

“We’re all from the north” was the sort of thing that sounded good until you tapped it and realised it was hollow as an empty bucket.

I’m sorry she hates you, he said.

And then he was like this too—he could say just the right thing, the words that swung in under your guard and got right to the core of you.

Me too, I said. But I don’t know what to do about it.

I’ve been thinking about it, he said.

She’s not your sister, I said. You don’t have to.

No, he said. But I can’t help thinking that she could have been. And what it must feel like.

He could get so close with his words that you had to hate him to keep yourself protected from him.

They poisoned her mind, he said. They must have done it to try and make her accept what had happened. To stop her trying to escape, because if you all had given her up, then where was she going to try and run to?

She was so young, I said.

This world? he said. It’s so far past old, nobody’s young any more. We’re all living on borrowed time.

That doesn’t mean anything, I said after I’d thought about it, giving his words another good tap in my mind.

I’m just trying to say we’re all on the edge, he said. You know what extinct means?

Sort of, I said. Yes.

Well, that’s us, he said. Humans. Sort of extinct.

That’s when we were talking. Now we’re not. It’s all because of the Leatherman and what I do at night. Which is lie under my bed and scratch away at the wall. I started doing it to mark the days, using the sharp screwdriver bit to mark a day in the paint. Except the paint cracked and flaked off and revealed the powdery plaster underneath. When I scraped some more I found the plaster was just a thin skin on top of those knobbly blocks you used to build with—bigger than bricks and with hollow spaces in between them. I went under the bed and did some more scraping, and very quickly had the plaster off a block and decided if I could move the block I could crawl into the next cell, and if I could do that I could maybe do it to the half-wall at the end under the bars where Joy had hit me.

Brand told me I was crazy.

Then he told me they would hear me.

Then he told me I would get us both in big trouble. And then he said he’d have to tell them if I carried on because even if they didn’t hear me at first, when they eventually found out I was trying to dig my way out they would know he had kept quiet.

I told him he had to do what he had to do. And I had to do what I was doing.

He didn’t tell them.

But he did stop talking to me.

I told you a book saved me. All the time I was lying on my side, scraping the cement out of the gap between the blocks I thought of The Count of Monte Cristo , an adventure of mistaken identities and a man who doesn’t give up as he tries to escape the impossible Chateau d’If.

My if was equally impossible. If I got through one wall, why did I think I could get through the next? But you can’t let ifs and buts stop you. So I kept eating and sleeping and writing in this notebook and scraping when I wasn’t and was sure the Cons weren’t around to hear. I became a sort of dazed character in my own adventure, unsure of the outcome, only knowing I could not stop, wherever I was going.

And however much I strained my eye to look for her, I never saw Joy again. Though some nights I would wake up and look at the window, sure that she had been watching me as I slept.

It was a stronger sense than a dream, almost tangible, like a scent of her in the mind, but whenever I jumped to the window to see her, the night was always empty and only peopled by my unfulfilled hopes drifting away in the dark.

Hope eventually became just like half the things that had stalked me on my journey across the mainland: not really there at all, just something prowling around me in my mind, distracting me from the darker truth of my situation.

There is one other reason Brand and I have stopped talking, and maybe I’m not writing about it because I’ve caught my story up to the now and every day is so much like the other that I’ve started to ration things.

Because when I have written it all down I won’t have you to talk to, and will truly be on my own.

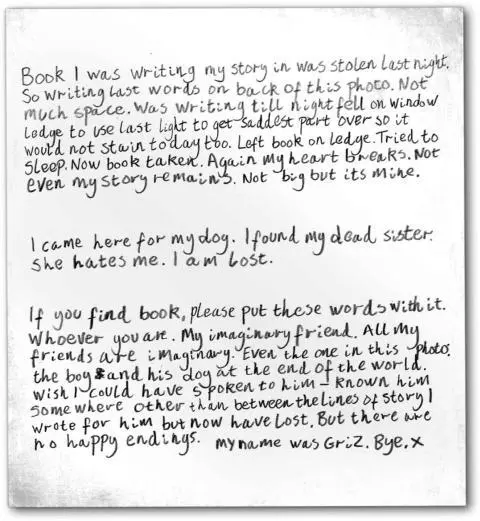

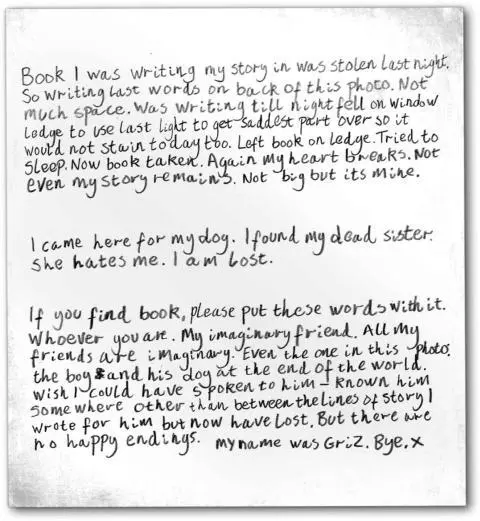

I am the one who took that photograph with that last bit of writing on the back and put it between the leaves you hold in your hand as you’re reading this. First I reread all the words that came before—the story in the book—some of them now hard to make out, the lines jammed in close to make the most use of the paper, sometimes so thinly scrawled I had to guess at what they were. And having got to the end, I thought that I should slide the photograph between the pages and explain how my story and that photograph came together and ended up so very far from the place my book was stolen. There are only a few of them, but I think there are enough empty pages left to do so.

Читать дальше