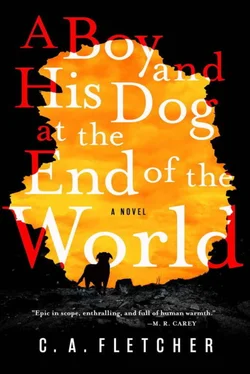

C Fletcher - A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «C Fletcher - A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2019, ISBN: 2019, Издательство: Orbit, Жанр: sf_postapocalyptic, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World

- Автор:

- Издательство:Orbit

- Жанр:

- Год:2019

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-316-44945-8

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It’s okay, Jip! I shouted. It’s okay.

But it wasn’t. Even as I manhandled the kayak over the taffrail, I could feel the keel grinding on the rocks below. I wondered whether I should lash the kayak down as I always did, or if I should leave it ready for a quick exit if the boat was holed and started to sink. Habit won and I tied it off with a quick-release knot, jumped down into the cockpit and tore open the cabin hatch. Jip hit me like a furry cannonball, jumping up, tail thumping away as his paws scrabbled at me, yelping and barking happily. Like all terriers, he wasn’t usually a soppy dog but he had clearly been scared by his confinement and the absence of a familiar person as the boat had swept away on its own.

Sorry, boy, sorry, I said and hugged him to me.

I allowed myself to bury my face in his fur while he licked away at my neck for a long moment. I think we both needed the physical contact with something familiar, something that loved us.

Then the boat lurched and I pushed him away and ducked into the cabin. I really needed to see if we were taking on water. A quick check seemed to show the hull was intact. The floor was dry all the way to the bow compartment. That was good news. But the grinding noise was worse below deck, where it had an added resonance that came through the soles of my boots. This close to, there was an ominous creaking undertone below it, like something was bending under the boat. I thought it was the keel and that it might be jammed in a crack in the rocks. It seemed to me there was every chance it might snap off or rip straight out of the bottom of the boat. Jip was standing in the hatchway looking at me, panting.

I grabbed the old saucepan we used as bailer and dog bowl and filled it from the canteen. He scrabbled down the steps and lapped the clean water greedily. I told him I’d feed him later and stepped up into the cockpit, ducking below the boom and looking over the side opposite the tide, trying to see exactly what we were stuck on.

It wasn’t rocks. I think if it had been rocks then maybe the waves would have smashed the Sweethope more than they did. What the boat was stuck on was a moveable object, itself drifting with the tide. At first I thought it was a boat, half sunk and drifting below the surface, but its sides and angles were all flat and right-angled. Then I realised it was a big metal shipping box, the size of a small house. There was one of them on Eriskay, mostly rusted out, on a wheeled trailer by the causeway. The majority of the paint on this one had gone and it had a thick beard of barnacles and seaweed dangling off its wrapping, which was a tangle of nylon fishing net. I crossed to the other side of the cockpit and saw the net was snarled round a second metal box floating end-on, nose down in the water. The first box must have had air trapped in it, making it more buoyant. It seemed like the keel of the boat was wedged in the gap between them. Because the boat was above water, the wind was trying to make it move faster than the current that was moving the boxes below, and that was what was twisting the keel.

I was going to have to cut the netting. And there was a lot of it. And the wind was getting up. So I was actually going to have to get it done before the keel snapped off. If the keel went, the bottom could rip out of the boat, or the boat could just capsize.

With the boathook and my knife, I set to work. I hooked the tangle of netting and pulled it to the surface and just started sawing at it. I didn’t have a plan of attack to begin with, but as I worked the twist of the current and the movement of the boat kept it taut and I was able to cut down the same row, strand after strand. The plastic your people made was strong stuff. We find so much of it now—I wonder if it will outlast us entirely. The netting bit back as I cut it. Sharp strands parted suddenly and scratched at the back of my hands as I worked the knife, and the palm of my right hand got blisters which then burst and stung in the salt water.

I don’t remember much from that afternoon, because it was gruelling, repetitive work and my side hurt from lying on the deck and leaning out over the water, and my back hurt from being bent over the gunwale all the time. I do remember stopping for water and making a lanyard for the knife because my grip was so painful I was worried about dropping it into the sea, and I do remember doing exactly that several times as the light began to dim all around, each time yanking it back up out of the depths and carrying on sawing away at the hard plastic strands. I also remember how the net suddenly untwisted at one point, slashing the side of my arm with a garland of sharp-edged shellfish that had colonised it. I’ve still got those two scars. And then—maybe because the part of the net that had been closest to the sunlight had rotted more than the strands I had started on—the thing suddenly came apart, and the heavier, nose-down cargo box dropped into the depths. Because it was already underwater, there was no noise and it was a strangely final but undramatic moment as it disappeared. The other one was more lively—freed of the counterweight, the air trapped in it bounced it higher in the water and though I moved fast, it still took skin off the back of my forearm as the rough tidemark of barnacles rasped across it. I swore and pulled back onto the boat.

The floating container rolled slowly on the surface like a lazy whale showing its belly to the sky, and then began to drift away as if it had never meant us any harm at all.

Cut loose, the Sweethope immediately felt different under my back. It bucked more in the chop—suddenly frisky—as if it really wanted to get moving again. And though I wanted to lie there and sleep for a while, I knew the boat was right and I had to get sails up and find somewhere to moor for the night.

Again, I have little memory of the rest of the afternoon, except I know I got the sails up and caught the wind and that Jip reminded me to feed him. And I know that the boat steered a bit differently to the way it always had, but I put that to the back of my mind. And most of all I remember that though I had the strongest heart-tug to turn her north and head home, I headed south-east, for the mainland. At the time I thought it was because it was close now, and so provided the best chance of a safe anchorage. Now I think I always knew I wasn’t going to give up on getting Jess back. And then again, I had never once set foot on the mainland itself. Curiosity, you see. It doesn’t just kill cats.

Chapter 11

Tilting at giants

I didn’t find a great place to moor, but the thin scrape of cove I did find was protected enough for a mild night. It was just luck that I still had Ferg’s anchor on board that I’d spent the day rescuing before Brand sailed into our lives, because without it I’d have been in trouble, the others still being on the sea bed to the west of Iona. I took that as a good omen and felt a little better as I made sure of my knots and dropped it over the side and waited anxiously until I was sure it had bitten into the bottom and was holding us steady. Then I went below and lit the lamp and did the two things I had been wanting to do all day. I ate some of the oatcakes and wind-dried mutton I’d grabbed from the kitchen at home, and I reached into my jerkin and took out the map I’d stolen from Brand’s boat and spread it out on the table.

Jip jumped up on the bench next to me and curled up with his chin on my thigh as I examined it. When he did that back at home, Jess would often take up a similar position on my other side, so that I was bookended by my dogs as I read. As I scratched his ears, my other hand automatically reached for hers before my brain told it she wasn’t there. It gave me a bit of a lurch, and so I concentrated on what was in front of me instead: it was a map of the mainland. It was printed on both sides, the top half on one, the bottom on the other. The land bits were crowded with place names and printed lines showing roads in different colours. The clear sea around it was covered in handwritten notes and numbers, none of which made much sense to me. What I only noticed when I flipped it over was that the lamplight winked through lots of tiny holes pricked all over it. The holes seemed to be random until I flipped the map back over and saw the pattern that made sense of it: the pinpricks matched places on the coast on each side, which of course meant that half of them appeared to be scattered randomly across dry land if you looked at them on the wrong side of the paper. I thought of the sharp set of dividers I’d jagged myself with in the dark. This was a map of where he’d been or where he was going—or both.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.