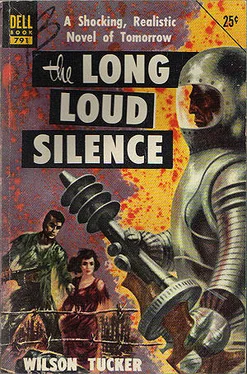

Wilson Tucker - The Long Loud Silence

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Wilson Tucker - The Long Loud Silence» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1952, ISBN: 1952, Издательство: Rinehart, Жанр: sf_postapocalyptic, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Long Loud Silence

- Автор:

- Издательство:Rinehart

- Жанр:

- Год:1952

- Город:New York

- ISBN:0-89968-375-4

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Long Loud Silence: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Long Loud Silence»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Long Loud Silence — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Long Loud Silence», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Bitterly, he realized he should have left the rotting officer behind. Rotting… the thought took form, shaped itself into a faint hope. It might be that they would not remove the suit from the lieutenant's body.

There were other things — he didn't know the names of people of Knox, he didn't know the history or background of Moskowitz… didn't so much as know the man's enlistment date. The serial numbers on the dog tag would give some clue to that, but he couldn't guess the accurate answer from the numbers. His only chance of escaping detection there lay in the fact that serial records may have been destroyed in a ravaged Washington.

The door opened and the corpsmen entered, carrying a tray.

“Another medal — you phony Egyptian!”

“I ain't no Egyptian,” Gary flared, half frightened.

“I'll say you ain't. AB hell! You ain't no more AB than I am. In case anybody asks, you're a big fat round O. Better remember that — you might need it sometime.”

“But the tag says—”

“The tag lies like a rug, chum, but don't let it throw you. You're an early bird, ain't you?” He put down the tray. “It happened all the time, back at the beginning; they rushed them through fast and made some mistakes. I'll bet one guy out of every twenty is walking around with the wrong type on his tag — or pushing up flowers. Sloppy work, but you can't help it. Only trouble is, if you ever need a transfusion in a hurry and they pump the wrong kind into you — bingo.”

“Maybe it changed,” Gary suggested. “It was a long time ago.”

“Nope.” The soldier shook his head and grinned at Gary's ignorance. “It never changes, no more than fingerprints. You was born with O and you'll die with O. Now eat up. I'll bring in water and a can pretty soon; you're stuck here until the tests prove out. Two or three days maybe.”

“What for?” he asked again. “Why the tests?”

“To see if you picked up anything, stupid. If you're carrying any plague germs around, we'll soon know it.” He backed away. “And I'll earn that damned medal.”

“That's a hell of a note. Listen — do me a favor. Put in for a pass for me. I've been out of circulation too long.”

“A pass he wants yet!”

Gary didn't get the pass — he never waited for it, never waited out the three days. He knew with certainty what those tests would reveal, knew beyond doubt that the test tubes or whatever things they used would point to his two years of wandering around the quarantined land, would shout what must be in his blood. Freedom was too near to wait three days.

He did nothing the first night, other than lie in the decontamination chamber and wait quietly. He called for and received repeated trays of food, a great quantity of water, the needed things a half-starved man would demand. And he noted with each opening and closing of the door that it was not locked from without. A single sentry stood outside, seldom at attention. They did not consider him a dangerous risk. Twice during the first night he sent out for water and once asked for more cigarettes. The sentry brought them, laid them in the doorway and retreated a few paces. Gary opened the door and hauled the things inside.

On the second day the medical corpsman brought paper and pencil and commenced questioning; he began in the routine way with Gary — or Moskowitz's immediate and current history, but quickly moved on to the journey made by the three truckloads of gold, and what happened to them. Gary hid his relief and spun an acceptable story. He included a vivid description of the country through which he had supposedly passed, and for spite threw in mention of the thousands of people they had seen, people hospitable and otherwise.

The questioner's head jerked up in disbelief. “Huh?”

“Huh, what?” It seemed that Gary had him hooked.

“Thousands of enemy agents?”

“I don't know if they were enemy agents or not,” Gary said casually, “but there were thousands of them all right. I don't mean in the cities — all the cities are dead and bombed out, we avoided those, but the little towns are full of people. Every time we passed through a whistle stop the whole damned population rushed out to greet us — just like those towns in France I went through.”

“But there can't be people over there, our people. They're all dead.”

Gary stared at him. “Why should I lie about it?”

“Well— I dunno.”

“All right. The burgs are full, believe me. Farmers in the field — a lot of the horses are dead, I guess, because I saw men pulling plows.” He hid a grin, watching the corpsman write down what he had said. The corpsman would do more than that — he would spread it around the camp. He went on with his story, bringing it up to the point where the ambush had wiped out everyone but him and the lieutenant — and the lieutenant had died a few hours later. And say — did the lieutenant get a military funeral?

“Hell, no,” the corpsman answered. “They weighted his body and dumped it in the river — ain't taking no chances.”

That night, the second in the chamber, Gary escaped.

He first considered asking the sentry for milk, knowing that milk would take longer to procure, but then quickly abandoned the idea with the knowledge that the sentry might well refuse — also being aware of the difficulty. Or if he did consent to go after it he might lock the door before leaving, or he might not be gone more than five minutes at the most. Five minutes were not enough. He needed hours to be free of the area.

Instead, Gary made the usual request for water and held the door opened the slightest crack, peering into the night. He could hear no one else near-by, could smell no tobacco smoke in the air. The sentry returned with the water and stooped to place it on the doorsill — stiffening with surprise when his eyes noticed the tiny crack in the opening. Gary caught him on the back of the neck, cracking the side of his hand on the man's spinal cord. The sentry slumped. Gary thrust his head outside warily but there was no outcry. Quickly then he dragged the inert body into the chamber and stretched it out along the far wall where he had slept the night before. Within seconds he had slipped outside and locked the door behind him, to vanish instantly into the surrounding darkness, away from the river.

He counted on three to four hours. At least three hours before the guard was scheduled to be relieved.

He was wearing civilian clothes, a pair of dirty coveralls and a nondescript sweater he had taken from a. farmer. A couple of dollars in change, also belonging to the throttled farmer, rattled around in his pocket The farmer's unconscious body lay many miles behind in a ditch but his ancient Ford truck sped along a highway to the south. Sunrise found Gary and the stolen truck nearly fifty miles south of St. Louis and well away from the river, well outside the ten-mile military zone.

This was freedom, this was what he had waited two years to see again.

He bowled along the highway at top speed, watching the unhurried activity about the farms, the sleepy beginnings of a new day in each small town he passed. There were no suspicious faces turned his way, no armed men to meet him at the village limits, no skulking figure to waylay the noisy truck as it sped along the road. This was free country, living country. Far behind him, unknown to him, not everything was so alive. A sentry lay dead in a decontamination chamber and a medical corpsman lay dying on a hospital bed, his body turning blue. Early alarm had turned to furore when the corpsman was discovered, and a hasty quarantine had been thrown around the camp guarding the bridge. Of a sudden two paramount problems had arisen for the responsible brass: finding the escaped carrier, and disposing of a few hundred men suddenly turned “enemy agents.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Long Loud Silence»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Long Loud Silence» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Long Loud Silence» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.