The babby says, “Wah!”

Punch says, “ O no dont cry you musnt cry. ”

The babby yels, “Wah!”

Punch says, “ O so juicy o so terbel juicy! ” He grabs the babby. No sooner does Punch get his hans on that babby nor in comes a big hairy han which it grabs Punch and my han inside Punch.

Its Easyer he yels, “You littl crookit barset I tol you not to try nothing here!”

Over goes the fit up and me and Punch and the babby and Easyer with it. 1 minim Easyers on top of me and the nex he dispears theres a han grabbit him sames his han grabbit Punch. Its Rightway Flinter which when I get my self untangelt from the fit up and on my feet its him and Easyer pulling datter to see which 1 wil walk a way when theyre finisht.

Its Rightway walks a way. Easyer is laid out flat. Rightway says to Riser Partman the regenneril guvner man from the Ram, “When he comes roun you myswel let him be Big Man here hewl work hard at it.”

Riser Partman he aint a bad looking kynd of man hes got inky fingers he says to Rightway, “What about you?”

Rightway says, “Ive got elser to be.”

We dint over the nite there we roadit out in to the dark which Rightway had it on him he wantit to be on the move right then. Him and his brother Deaper they boath come with us they dint want to stop at Weaping no mor. They boath of them have wives and childer the woal lot roadit out with us they jus slung ther bundels and a way.

When we gone out thru the gate there wer a kid up on the hy walk sames I use to be up there all times of nite when I wer a kid. 7 or 8 he wer may be. Sharp littl face liting and shaddering in the shimmying of the gate house torches. Sharp littl face and he begun to sing:

“Riddley Walkers ben to show

Riddley Walkers on the go

Dont go Riddley Walkers track

Drop Johns ryding on his back”

Now whered that kid ever hear of Drop John and what put it in his mynd to sing that of me? Why dint I ask him? I dont know. May be I dint want to know.

Why is Punch crookit? Why wil he all ways kil the babby if he can? Parbly I wont never know its jus on me to think on it.

Riddley Walkers ben to show

Riddley Walkers on the go

Dont go Riddley Walkers track

Drop Johns ryding on his back

Stil I wunt have no other track.

The end

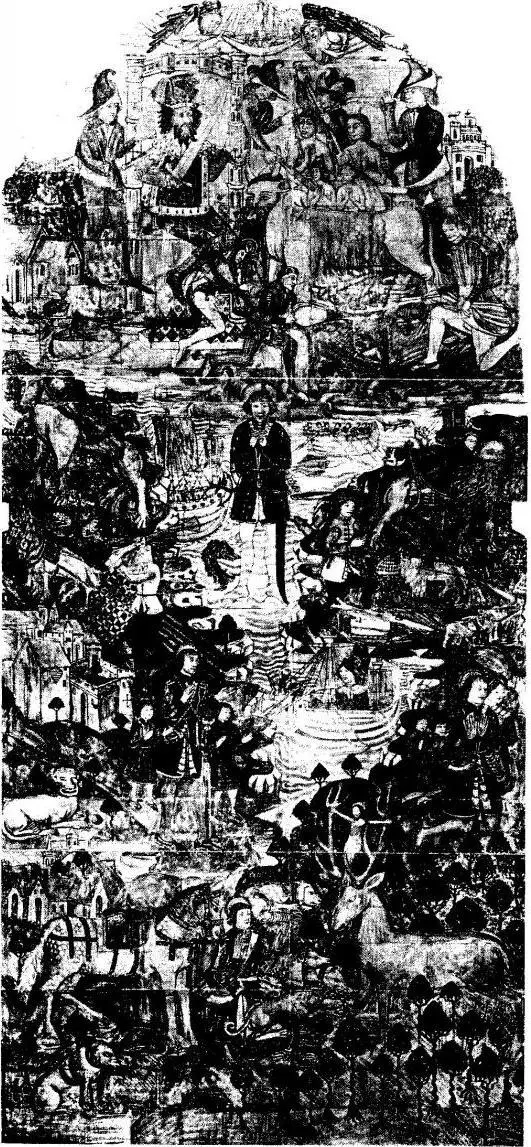

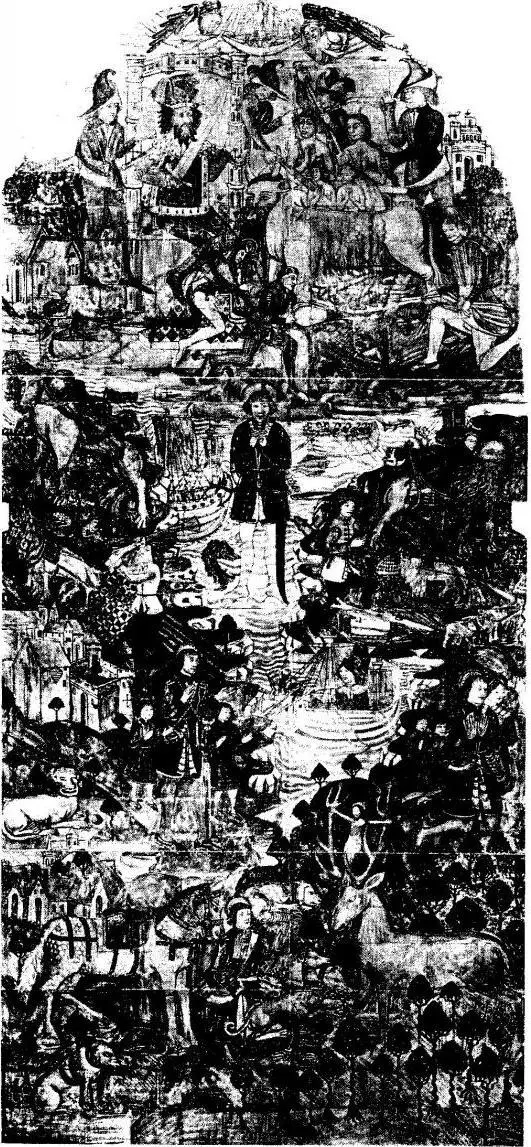

“The Legend of St. Eustace.” Reconstruction by Professor Tristram of wall painting (c. 1480) in the north choir aisle of Canterbury Cathedral. Reproduced with the permission of the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury.

Only faint earth-green outlines remain of the fifteenth century wall painting, The Legend of St Eustace , in the north choir aisle of Canterbury Cathedral. Across the aisle from it is Dr Tristram’s reconstruction, in sections, with the printed legend. The story of Eustace moves from the bottom to the top of the vertical composition, the scale of the figures and other elements varying according to their importance and chronology. The central figure and the largest, the one to which the eye is immediately drawn, is that of Eustace standing in a river, praying. His wife has been carried off by pirates and now his two little sons are taken away, one by a lion on the right bank and the other by a wolf on the left bank. Eustace is all alone in the middle of the river, hoping for better times. Seeing him for the first time that day in 1974 I had a strong fellow-feeling.

People ask me how I got from St Eustace to Riddley Walker and all I can say is that it’s a matter of being friends with your head. Things come into the mind and wait to hook up with other things; there are places that can heighten your responses, and if you let your head go its own way it might, with luck, make interesting connections. On March 14th, 1974 I got lucky.

It was my first visit to Canterbury; I’d given a talk at the Teachers’ Centre the evening before, and next morning my host, Dennis Saunders, County Inspector for English, showed me around the cathedral. I’m writing this in 1998, in the Oprah Winfrey era when millions are bursting to share their most private experiences with other millions; but I find that the Canterbury in me, having worded its way into Riddley Walker , wants to stay mostly unworded now. The cathedral is what it is; as soon as we came into the nave I could feel the action of the place, and by the time we reached The Legend of St Eustace I was ready for something to happen. As I stood before the picture there came to me the idea of a desolate England thousands of years after the destruction of civilisation in a nuclear war; people would be living at an Iron Age level of technology and such government as there was would make its policies known through itinerant puppeteers. I know it sounds strange but that’s how it was.

Why puppets? Punch and Judy had been in my thoughts ever since reading, some time before coming to England, two New Yorker articles by Edmund Wilson about English puppeteers. I hadn’t yet seen a show but soon after my Canterbury visit I saw Percy Press and Percy Press Jr do one in Richmond; after that it was inevitable that Mr Punch would find his way into Riddley Walker sooner or later.

In my first Page One on May 14th there was a Eusa man with puppets but the writing was in standard English. Here are my first paragraphs:

The Eusa man stood outside in the rain and sent his partner in first. The partner was well over six feet tall, had a bow and a quiver of arrows on his back, a big knife, and four rabbits hanging from his belt. He had hands that looked as if they could break anything or squeeze it to death. He poked about with his spear, looked here and there behind things. He seemed to take the place in with all his senses at once, took in the feel of it as an animal would.

The Eusa man stood with his bundle on his back and leant on his stick while the steam came up from his sweating back and the dogs sniffed him. He didn’t seem to mind the rain that came down on his little old hat or the mud he stood in.

“Okay,” said the partner.

The Eusa man bent down so his bundle would clear the opening and came inside.

“Wotcher?” he said.

That first Page One had domesticated dogs in it but soon these disappeared and in later drafts the only dogs were the killers that Riddley became friendly with. I like those dogs; there needed to be danger outside the fences and they were it—forlorn and murderous, full of lost innocence and the 1st knowing. Activated by the ancient blackened Punch he finds in the mud at Widders Dump, Riddley goes over the fence and joins up with the danger that’s waiting for him.

In that first Chapter One the Littl Shynin Man hasn’t yet become the Addom—he’s Lilla Jesu. From the start the story had a life of its own; the metamorphosis of Lilla Jesu into the Addom showed that it was finding its way.

Early on the language began to slide towards Riddleyspeak; I like to play with sounds, and when alone in the house I often talk in strange accents and nonsense words. The grammatical decline began with the dropping of the auxiliary verb in the present perfect tense; many of the children I went to school with in Pennsylvania spoke that way: “I been there” and “I done that.” One thing led to another, and the vernacular I ended up with seems entirely plausible to me; language doesn’t stand still, and words often carry long-forgotten meanings. Riddleyspeak is only a breaking down and twisting of standard English, so the reader who sounds out the words and uses a little imagination ought to be able to understand it. Technically it works well with the story because it slows the reader down to Riddley’s rate of comprehension.

Читать дальше