The eyes remained. Still, like knots in a tree.

His mind raced back to the voices of his grandfather and the other old men that he would listen to at the camp on the edge of the bayou. To the things they had seen and the tall tales they had told and he tried to figure out what those orange eyes belonged to but all the voices of the old men did was conjure images of swamp monsters and nameless bloodthirsty creatures that lifted children from their beds in the middle of the night. The eyes staring at him were real and they were close and they were paying attention with an uncommon patience.

It’s gotta be a panther, he thought. A big-ass panther.

He unbuttoned the sheath and pulled out the knife and tried to figure out the best way to kill a panther or whatever the hell it was and he smiled a dumb smile at the absurdity of the thought.

Cohen shifted his gaze to the horse when she snorted again and when he looked back, the orange eyes were gone. Vanished in the dark as if he might have imagined them. He breathed, unaware that he had been holding his breath. And then he told the dog to relax. For now. He stood slowly and walked around to the side of the church and he called the dog and Habana to follow. There would be no sleeping near the fire tonight, not with that thing so close. So the three of them went through a back door of the church and into the room where he had found the choir robes. There were more piled in a closet, and he felt around in the dark and grabbed several and laid them across the floor. The dog immediately lay down on them but he told it to get up. Cohen picked up one of the robes and wrapped it around himself and then he went back to the door, feeling his way with his hand on the wall, and he closed it. Back in the room, he lay down on the robes and the dog lay next to him and Habana stood at the window with her nostrils against the glass and her breath fogging the window. They would be cold and they would be uncomfortable, but they would be safe. And then he started talking to the dog again.

SINCE THE PROCLAMATION OF THE line, they came down like packs of wild coyotes coming in from the hillsides after smelling the scent of fresh blood. Some like gangbusters, with coolers of beer and good weed and radios blaring through the rainstorms, whooping and hollering like crazed spring breakers certain they were having a good time. They crashed the beach, milled around an upturned casino, and started digging not in unison or with any goal but all heads working independently and the holes they dug weren’t large enough to hide a basketball in, much less trunks filled with millions of dollars. The gangbusters didn’t last. They drove hours, maybe days, to get down to the coast, unaware of the severity of the life below the Line, and they left almost as quickly as they arrived, once the buzz wore off and the shots were fired over their heads.

Others knew the terrain. Those that remained below. Those that knew the winds, knew the thunder, knew the gaps in the seaside and where the bridges were washed away, and knew the lineup of casinos that once stretched for twenty miles along the shore. They knew which ones were still there, and if they weren’t still there, they knew where they had once been.

What separated the others were the tools they worked with. Those with no chance came in bunches of four or five, riding in truck beds, shovels and pickaxes for each man. They knew the landscape, had the heart but no guns and no strength or energy to dig quickly and make any headway before being seen and having to make a run for it back into the soggy hole they had crawled out of.

Those with a chance, if there was actually anything to be found, had the guns, had youth, had the vehicles to get through, or across, or over. Men in army-green jeeps and trucks, four-wheel-drive vehicles made for war, with gadgets that detected metal underneath the ground. Men who possessed the physical strength and training to work hard, dig deep, make haste. Men who had been left behind by their government, stuck in outposts in the region below the Line, for God knows what. To help those who didn’t want to be helped. To protect those who didn’t want protection. To sit in steel-braced cinder-block outposts, day after day, ducking from the storms, watching the rain, listening to the snap of lightning and the moan of thunder, staring at the walls and staring at the floors, so the same government that had abandoned the region could still maintain authority over it, even though there was no law to be followed. No law to be made other than what seemed right at the time. These were the men who sat there day after day, because they had been ordered to by other men who lived on dry land, and now they had grown restless and anxious and this was their opportunity to get out and go and do something and they came in their jeeps and trucks, their big guns racked on top or showing out of the open windows, to express to whoever might be interested in the same treasure they were looking for—do not fuck with us.

The coast was crawling with them and they all came after the same thing—the buried casino money. A lot of damn buried casino money. In the panic of the evacuations, and later in the panic of the Line becoming official, it had been rumored that casino executives ordered the burying of trunks of cash in an effort to hide it from the taxman. The less money the casinos moved, the less money they had to claim. Rumors swirled of men in the middle of the night, loading the backs of trucks with trunks large enough to hide bodies, filled with stacks of crisp dollar bills, and then disappearing into the dark to deposit them into the earth.

The rumors of the buried money were not dispelled easily. In newspaper articles and magazine exposés that covered the movement of the casinos and banks and other financial institutions from the region, the buried money was consistently part of the conversation. The men in the suits flatly denied it, but there was always some casino services manager or pit boss or cocktail waitress who had been in the right bed, ready to proclaim that it was not some ridiculous rumor, I saw the money being loaded, so-and-so told me about burying the money and then he laughed because he said it was so primitive and brilliant at the same time, not only were the big trunks taken out and buried but the big shots filled up their own bags and stashed them across the coast as a retirement plan. The economy was breaking down and banks were folding and many of the casinos were not reopening elsewhere and cash was what mattered. And it’s out there. Somewhere.

So they came looking.

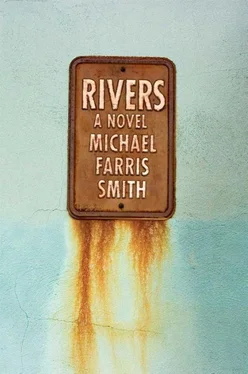

Part II

THE NEXT MORNING, COHEN GOT up and he decided what to take and not to take. In the corner of the room where they slept, in a small closet, he left his extra clothes, some food, and all but one of the paperbacks. He fed the dog what was left of the dog biscuits and then he gathered the rest of the food and water and went outside. He put the food and water and aspirin in Habana’s saddlebag along with the flashlight and some matches and the book. In his back pocket remained the picture of Elisa and in his front the small socks. He then covered himself with one of the purple robes and mounted the horse. He looked down at the dog and told it to stay, I’m coming back here at some point in the next few days. But the dog ignored him and walked and then trotted along with them.

A gold cross decorated the back of the robe and Cohen had the appearance of a medieval crusader scouring a godless land in the name of the Almighty. For the next three days, he suffered the rain, rode Habana, and looked for his Jeep and the two who had taken it but he spent most of his time ducking away from others he came across. More movement than he had seen on the coast since before the Line. There was movement along the beachfront, movement in the wastelands of the casinos and hotels and restaurants. Movement even in the scattered remains of the neighborhoods of Gulfport, where there was usually only the quiet of the world of concrete foundations and chimneys. He hid away and watched them. Groups of men standing in a spot and digging. And then maybe gunfire, and ducking and dodging and driving off fast in any direction. He came upon this a couple of times a day, and he had no choice but to hide, and watch them through the rain, and marvel at their dedication to a legend.

Читать дальше