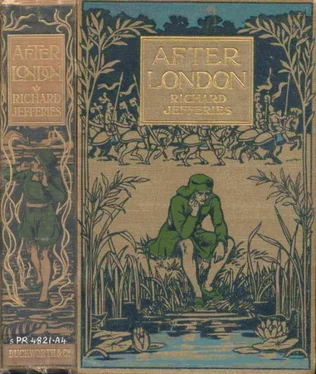

Richard Jefferies - After London

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Richard Jefferies - After London» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 1905, Издательство: Duckworth & Co., Жанр: sf_postapocalyptic, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:After London

- Автор:

- Издательство:Duckworth & Co.

- Жанр:

- Год:1905

- Город:London

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

After London: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «After London»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

(1885), set in a future in which urban civilization has collapsed after an environmental crisis.” (From

).

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

* * *

After London — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «After London», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In another half hour he arrived at the opening of the strait; it was about a mile wide, and either shore was quite flat, that on the right for a short distance, the range of downs approaching within two miles; that on the left, or north, was level as far as he could see. He had now again to lower his sail, to get the outrigger on his lee as he turned to the right and steered due east into the channel. So long as the shore was level, he had no difficulty, for the wind drew over it, but when the hills gradually came near and almost overhung the channel, they shut off much of the breeze, and his progress was slow. When it turned and ran narrowing every moment to the south, the wind failed him altogether.

On the right shore, wooded hills rose from the water like a wall; on the left, it was a perfect plain. He could see nothing of the merchantman, although he knew that she could not sail here, but must be working through with her sweeps. Her heavy hull and bluff bow must make the rowing a slow and laborious process; therefore she could not be far ahead, but was concealed by the winding of the strait. He lowered the sail, as it was now useless, and began to paddle; in a very short time he found the heat under the hills oppressive when thus working. He had now been afloat between six and seven hours, and must have come fully thirty miles, perhaps rather more than twenty in a straight line, and he felt somewhat weary and cramped from sitting so long in the canoe.

Though he paddled hard he did not seem to make much progress, and at length he recognised that there was a distinct current, which opposed his advance, flowing through the channel from east to west. If he ceased paddling, he found he drifted slowly back; the long aquatic weeds, too, which he passed, all extended their floating streamers westward. We did not know of this current till Felix Aquila observed and recorded it.

Tired and hungry (for, full of his voyage, he had taken no refreshments since he started), he resolved to land, rest a little while, and then ascend the hill, and see what he could of the channel. He soon reached the shore, the strait having narrowed to less than a mile in width, and ran the canoe on the ground by a bush, to which, on getting out, he attached the painter. The relief of stretching his limbs was so great that it seemed to endow him with fresh strength, and without waiting to eat, he at once climbed the hill. From the top, the remainder of the strait could be easily distinguished. But a short distance from where he stood, it bent again, and proceeded due east.

CHAPTER XIV

THE STRAITS

The passage contracted there to little over half a mile, but these narrows did not continue far; the shores, having approached thus near each other, quickly receded, till presently they were at least two miles apart. The merchant vessel had passed the narrows with the aid of her sweeps, but she moved slowly, and, as it seemed to him, with difficulty. She was about a mile and a half distant, and near the eastern mouth of the strait. As Felix watched he saw her square sail again raised, showing that she had reached a spot where the hills ceased to shut off the wind. Entering the open Lake she altered her course and sailed away to the north-north-east, following the course of the northern mainland.

Looking now eastwards, across the Lake, he saw a vast and beautiful expanse of water, without island or break of any kind, reaching to the horizon. Northwards and southwards the land fell rapidly away, skirted as usual with islets and shoals, between which and the shore vessels usually voyaged. He had heard of this open water, and it was his intention to sail out into and explore it, but as the sun now began to decline towards the west, he considered that he had better wait till morning, and so have a whole day before him. Meantime, he would paddle through the channel, beach the canoe on the islet that stood farthest out, and so start clear on the morrow.

Turning now to look back the other way, westward, he was surprised to see a second channel, which came almost to the foot of the hill on which he stood, but there ended and did not connect with the first. The entrance to it was concealed, as he now saw, by an island, past which he must have sailed that afternoon. This second or blind channel seemed more familiar to him than the flat and reedy shore at the mouth of the true strait, and he now recognised it as the one to which he had journeyed on foot through the forest. He had not then struck the true strait at all; he had sat down and pondered beside this deceptive inlet thinking that it divided the mainlands. From this discovery he saw how easy it was to be misled in such matters.

But it even more fully convinced him of the importance of this uninhabited and neglected place. It seemed like a canal cut on purpose to supply a fort from the Lake in the rear with provisions and material, supposing access in front prevented by hostile fleets and armies. A castle, if built near where he stood, would command the channel; arrows, indeed, could not be shot across, but vessels under the protection of the castle could dispute the passage, obstructed as it could be with floating booms. An invader coming from the north must cross here; for many years past there had been a general feeling that some day such an attempt would be made. Fortifications would be of incalculable value in repelling the hostile hordes and preventing their landing.

Who held this strait would possess the key of the Lake, and would be master of, or would at least hold the balance between, the kings and republics dotted along the coasts on either hand. No vessel could pass without his permission. It was the most patent illustration of the extremely local horizon, the contracted mental view of the petty kings and their statesmen, who were so concerned about the frontiers of their provinces, and frequently interfered and fought for a single palisaded estate or barony, yet were quite oblivious of the opportunity of empire open here to any who could seize it.

If the governor of such a castle as he imagined built upon the strait, had also vessels of war, they could lie in this second channel sheltered from all winds, and ready to sally forth and take an attacking force upon the flank. While he pondered upon these advantages he could not conceal from himself that he had once sat down and dreamed beside this second inlet, thinking it to be the channel. The doubt arose whether, if he was so easily misled in such a large, tangible, and purely physical matter, he might not be deceived also in his ideas; whether, if tested, they might not fail; whether the world was not right and he wrong.

The very clearness and many-sided character of his mind often hindered and even checked altogether the best founded of his impressions, the more especially when he, as it were, stood still and thought. In reverie, the subtlety of his mind entangled him; in action, he was almost always right. Action prompted his decision. Descending from the hill he now took some refreshment, and then pushed out again in the canoe. So powerful was the current in the narrowest part of the strait that it occupied him two hours in paddling as many miles.

When he was free of the channel, he hoisted sail and directed his course straight out for an island which stood almost opposite the entrance. But as he approached, driven along at a good pace, suddenly the canoe seemed to be seized from beneath. He knew in a moment that he had grounded on soft mud, and sprang up to lower the sail, but before he could do so the canoe came to a standstill on the mud-bank, and the waves following behind, directly she stopped, broke over the stern. Fortunately they were but small, having only a mile or so to roll from the shore, but they flung enough water on board in a few minutes to spoil part of his provisions, and to set everything afloat that was loose on the bottom of the vessel.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «After London»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «After London» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «After London» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.