Murray Leinster - Sand Doom

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Murray Leinster - Sand Doom» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2007, Жанр: Космическая фантастика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Sand Doom

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2007

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Sand Doom: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Sand Doom»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Sand Doom — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Sand Doom», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Those side-fins,” said Chuka’s deep voice pleasantly, “the bottom ones, make things better for you. The shade overhead cuts off direct sunlight, and they cut off the reflected glare. It would blister your skin even if the sun never touched you directly.”

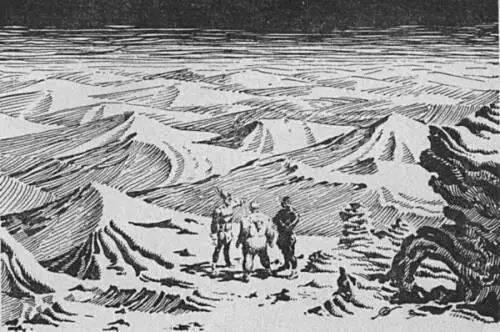

Bordman did not answer. The caterwheel car went on. It came to a patch of sand—tawny sand, heavily mineralized. There was a dune here. Not a big one for Xosa II. It was no more than a hundred feet high. But they went up its leeward, steeply slanting side. All the planet seemed to tilt insanely as the caterwheels spun. They reached the dune’s crest, where it tended to curl over and break like a water-comber, and here the wheels struggled with sand precariously ready to fall, and Bordman had a sudden perception of the sands of Xosa II as the oceans that they really were. The dunes were waves which moved with infinite slowness, but the irresistible force of storm-seas. Nothing could resist them. Nothing!

They traveled over similar dunes for two miles. Then they began to climb the approaches to the mountains. And Bordman saw for the second time—the first had been through the ports of the landing-boat—where there was a notch in the mountain wall and sand had flowed out of it like a waterfall, making a beautifully symmetrical cone-shaped heap against the lower cliffs. There were many such falls. There was one place where there was a sand-cascade. Sand had poured over a series of rocky steps, piling up on each in turn to its very edge, and then spilling again to the next.

They went up a crazily slanting spur of stone, whose sides were too steep for sand to lodge on, and whose narrow crest had a bare thin coating of powder.

The landscape looked like a nightmare. As the car went on, wabbling and lurching and dipping on its way, the heights on either side made Bordman tend to dizziness. The coloring was impossible. The aridness, the desiccation, the lifelessness of everything about was somehow shocking. Bordman found himself straining his eyes for the merest, scrubbiest of bushes and for however stunted and isolated a wisp of grass.

The journey went on for an hour. Then there came a straining climb up a now-windswept ridge of eroded rock, and the attainment of its highest point. The ground car went onward for a hundred yards and stopped.

They had reached the top of the mountain range, and there was doubtlessly another range beyond. But they could not see it. Here, at the place to which they had climbed so effortfully, there were no more rocks. There was no valley. There was no descending slope. There was sand. This was one of the sand plateaus which were a unique feature of Xosa II. And Bordman knew, now, that the disputed explanation was the true one.

Winds, blowing over the mountains, carried sand as on other worlds they carried moisture and pollen and seeds and rain. Where two mountain ranges ran across the course of long-blowing winds, the winds eddied above the valley between. They dropped sand into it. The equivalent of trade winds, Bordman considered, in time would fill a valley to the mountain tops, just as trade winds provide moisture in equal quantity on other worlds, and civilizations have been built upon it. But——

“Well?” said Bordman challengingly.

“This is the site of the landing grid,” said Redfeather.

“Where?”

“Here,” said the Indian dryly. “A few months ago there was a valley here. The landing grid had eighteen hundred feet of height built. There was to be four hundred feet more—the lighter top construction justifies my figure of eighty per cent completion. Then there was a storm.”

It was hot. Horribly, terribly hot, even here on a plateau at mountaintop height. Dr. Chuka looked at Bordman’s face and bent down in the vehicle. He turned a stopcock on one of the air tanks brought for Bordman’s necessity. Immediately Bordman felt cooler. His skin was dry, of course. The circulated air dried sweat as fast as it appeared. But he had the dazed, feverish feeling of a man in an artificial-fever box. He’d been fighting it for some time. Now the coolness of the expanded air was almost deliriously refreshing.

Dr. Chuka produced a canteen. Bordman drank thirstily. The water was slightly salted to replace salt lost in sweat.

“A storm, eh?” asked Bordman, after a time of contemplation of his inner sensations as well as the scene of disaster before him. There’d be some hundreds of millions of tons of sand in even a section of this plateau. It was unthinkable that it could be removed except by a long-time sweep of changed trade winds along the length of the valley. “But what has a storm to do——”

“It was a sandstorm,” said Redfeather coldly. “Probably there was a sunspot flare-up. We don’t know. But the pre-colonization survey spoke of sandstorms. The survey team even made estimates of sandfall in various places as so many inches per year. Here all storms drop sand instead of rain. But there must have been a sunspot flare because this storm blew for”—his voice went flat and deliberate because it was stating the unbelievable—“for two months. We did not see the sun in all that time. And we couldn’t work, naturally. The sand would flay a man’s skin off his body in minutes. So we waited it out.

“When it ended, there was this sand plateau where the survey had ordered the landing grid to be built. The grid was under it. It is under it. The top of eighteen hundred feet of steel is still buried two hundred feet down in the sand you see. Our unfabricated building-steel is piled ready for erection—under two thousand feet of sand. Without anything but stored power it is hardly practical”—Redfeather’s tone was sardonic—“for us to try to dig it out. There are hundreds of millions of tons of stuff to be moved. If we could get the sand away, we could finish the grid. If we could finish the grid, we’d have power enough to get the sand away—in a few years, and if we could replace the machinery that wore out handling it. And if there wasn’t another sandstorm.”

He paused. Bordman took deep breaths of the cooler air. He could think more clearly.

“If you will accept photographs,” said Redfeather politely, “you can check that we actually did the work.”

Bordman saw the implications. The colony had been formed of Amerinds for the steel work and Africans for the labor the Amerinds were congenitally averse to—the handling of complex mining-machinery underground and the control of modern high-speed smelting operations. Both races could endure this climate and work in it—provided that they had cooled sleeping quarters. But they had to have power. Power not only to work with, but to live by. The air-cooling machinery that made sleep possible also condensed from the cooled air the minute trace of water vapor it contained and that they needed for drink. But without power they would thirst. Without the landing grid and the power it took from the ionosphere, they could not receive supplies from the rest of the universe. So they would starve.

And the Warlock , now in orbit somewhere overhead, was well within the planet’s gravitational field and could not use its Lawlor drive to escape with news of their predicament. In the normal course of events it would be years before a colony ship capable of landing or blasting out of a planetary gravitational field by rocket-power was dispatched to find out why there was no news from Xosa II. There was no such thing as interstellar signaling, of course. Ships themselves travel faster than any signal that could be sent, and distances were so great that mere communication took enormous lengths of time. A letter sent to Earth from the Rim even now took ten years to make the journey, and another ten for a reply. Even the much shorter distances involved in Xosa II’s predicament still ruled out all hope. The colony was strictly on its own.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Sand Doom»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Sand Doom» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Sand Doom» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.