Kim Robinson - Icehenge

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Kim Robinson - Icehenge» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1998, ISBN: 1998, Издательство: Orb Books, Жанр: Космическая фантастика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Icehenge

- Автор:

- Издательство:Orb Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1998

- ISBN:0312866097

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Icehenge: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Icehenge»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

contains elements that should be familiar to readers of the Mars series. Extreme human longevity, Martian revolution, historical revisionism, and shifts between primary characters are all present.

Icehenge

Icehenge — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Icehenge», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Can’t you use urea and ammonia exclusively,” I asked them, “and shift amounts of pyrenoidosa and vulgaris to keep the exchange balanced? That way you’d be using more urea, and avoiding the problem of nitrates.”

They looked at each other.

“Well, no,” Nadezhda said. “See, look at this — the damn algae grow so fast with urea — too much biomass, we can’t use it all.”

“What about giving it less light?”

“But that makes for problems with the vulgaris,” Marie-Anne explained. “Stupid stuff, it either dies or grows wild.”

Clearly I was repeating the most obvious solutions. Problem-solving for a biologic life-support system is like a game. One of the very finest intellectual games ever devised, in fact. In many ways it is like chess. Now, Nadezhda and Marie-Anne were certainly grand masters at this game, and they had been working with this particular model for years. So they were a big step ahead of me at that moment, discussing modifications that I had never heard of. But I had never met anybody who had a flair for the game like I did — if it had been chess, I would have been Martian champion, I am sure. When I saw the patient look on Marie-Anne’s face as she explained why my suggestion wouldn’t work, something snapped in me, and my vague intentions for this visit crystallized.

“All right,” I said in a mean tone of voice. “You’d better give me the whole story here, all the details of your model, your new improvements that Swann told me about, everything. If you want me to help.”

The two women nodded politely, as if this request were the most ordinary thing in the world. And we got down to it.

So I helped them, yes, I did. And more than ever before, the I who thought and felt was distanced from the I who did the work on this particular example of the BLSS problem — more than ever the work seemed a game, a giant intricate puzzle that we would look at when we finished — we would stand back to look at it, and admire it, and then we would forget it and go home to dinner. In this frame of mind I was especially inventive, and I helped a lot.

It got to the point where I even began to return to the starship in the evenings after dinner, to wander the farm alone and type some figures into the model programs to check the results. Because they had a real problem on their hands — I’d never worked on a harder one. The two ships were Deimos PRs: about forty years old, shaped like decks of cards, just over a kilometer long; powered by cesium reactor-mass, deuterium-fueled, direct-explosion rockets. The crew of forty or forty-five lived in the forward or upper part of the ships, behind the bridges. Below them were the recreational facilities, the various chambers of the farms, and the recycling plants, and below those were the huge masses of the rocket systems, and the shield that protected the crews from them. The ships were biogeocenoses, that is, enclosed ecologic systems, combining biologic and technologic methods to create closures. Total closure was not possible, of course; it approached eighty percent complete for a three-year period, tailing off rapidly after that. So they were good asteroid miners, they really were. But there were loss-points that had never been satisfactorily solved, and although these were the best closed biologic life-support systems ever built, they were no starships.

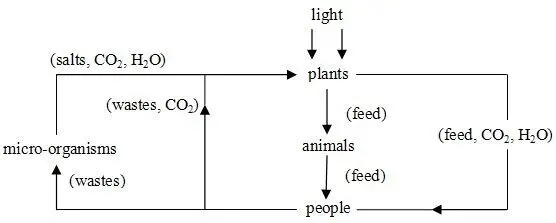

I walked in circles through the rooms of Hidalgo’s farm, following the course of the various processes as I tried to think my way through the system. Most of the rooms were darkened, but the algae rooms still required sunglasses. Here the whole thing began. Heat and light generated by the nuclear reactions in the rocketry provided energy for the photoautotropic plants, mostly the algae chlorella pyrenoidosa and chlorella vulgaris. These were suspended in large bottles under the lights, and I thought that, despite the nutrient problems, they could be manipulated genetically or environmentally to make the gas exchange as needed. I took off the sunglasses and stumbled around the darkened aqua room until my sight returned. Here the excess algae was brought to feed the bottom of the food chain. Plankton and crustacea ate algae, little fish ate the plankton, big fish ate the little fish. It was the same in the barns farther along; under night lights I could make out the cages and pens for the rabbits, chickens, pigs and goats — and my nose confirmed their presence. These animals ate the plant wastes that humans didn’t use, and provided food themselves. Beyond the animals’ barn was the series of rooms planted with rows of vegetables — the farm proper — and here some lights were still on, providing a pleasant, mild illumination. I sat down against one wall and looked at a long row of cabbages. Beside me on the wall was drawn a simple schematic, left wordless like a religious token — a diagram of the system’s circular processes. Light fed algae. Algae fed plants and fish. Plants fed animals and humans, and created oxygen and water. Animals fed humans, and humans and animals created wastes which sustained microorganisms that mineralized the wastes (to an extent), making it possible to plow them back into the plants’ soil.

The cabbages glowed in the dim light like rows of brains, working on the problem with me. The circle made by the diagram, supplemented by physiochemical operations to aid the gas exchange and the use of wastes, was nearly closed: a neat, reliable, artificial biogeocenosis. But there were two major loss points that had me stumped; and I wasn’t going to see the solution walking around the farm. One was the incomplete use of wastes. Direct use of human waste products as nutrients for plant life is limited by the build-up of chlorine ions not used by plants. Sodium chloride, for instance, is a compound used by human beings as a palatable substance, but it isn’t required in equivalent amounts by the other components of the system. So the use of algae to mineralize wastes on Hidalgo had to be supplemented by physiochemical mineralization — thermal combustion in this case, which resulted in a small but significant amount of useless furnace ash. It would be difficult to find ways to return those poorly soluble metal oxides into the system.

The other major problem was the very minute disappearance of water. Though water could be filtered out of the air, and recaptured in a number of ways, a certain percentage would coat the interior of the ship, bond with various surfaces, pool in cracks and hidden spots on the floor, and even escape the ship if they ever had EVA.

And the more I thought of it, the more little problems appeared to augment these larger ones, and all of the problems impinged on each other, making a large and interconnected web of cause and effect, mostly measurable, but sometimes not… the game. The hardest game. And this time, by these people, played for keeps.

I got up nervously and paced between the long soil strips. They could create water using a fuel cell and electrolysis. With the power plant they had along, that might be all they would need. It would depend on their water recovery, their fuel supply, the amount of time they spent between stars. I turned and headed for the farm computers, intent on trying some figures. And as for those wastes, Marie-Anne had spoken of new mutant bacteria to mineralize them, bacteria that could chew up the metals they would slowly be piling up outside the system…

The whoosh of the vents, the clicking of a counter, the soft snuffling of the animals in their sleep. Maybe they could do it, I thought. A very high degree of closure might be possible. But the question was, once accomplished, would they want to live inside it?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Icehenge»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Icehenge» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Icehenge» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.