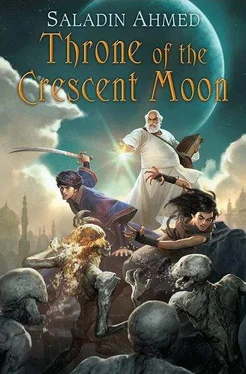

Little Square was a haven for the less prosperous merchants and tradesmen of the city—those too poor or too unreliable to have earned, through honest work or bribery, a real shop or stall in one of the better markets. The square was flanked by these men and women, sitting on rugs or standing beside sorry piles of goods. Adoulla’s eyes moved up the column of half-rate cobblers and rotten-vegetable sellers to his right.

He cursed as he caught sight, a dozen yards ahead, of a skinny man in the white kaftan of his order. He strode over and made the noise in his throat that he made when genuinely offended. Litaz had once said that it sounded like he was being pleasured by a poorly trained whore.

For all that he mocked Raseed’s dervishhood, Adoulla had also pledged his life to an antiquated order that Dhamsawaatis knew mostly from great-grandparents’ tales and bawdy shadow-puppet plays. Adoulla had learned long ago that most men professing his life-calling were charlatans who had bits and pieces of the proper knowledge but had never been face-to-face with a ghul. They used cheap magic to make their robes appear moonlight white and took the hard-earned money of the poor, mumbling a few bogus spells and promising protection from monsters.

The hairy young man with an oily smile who stood before him wore such cheap robes. He was the sort who claimed to hunt the “hidden spirits” supposedly behind working peoples’ every trouble. The sort who claimed to tell the future. The rotten-vegetable sellers of my order .

When he was a younger man, and more defensive of the honor of his order, Adoulla had thought it his duty to root out such hucksters and send them packing with their robes dirtied and their noses and false charms broken. But the decades since had taught him resignation. Other charlatans would always pop up, and the people—the desperate, desperate people—would always go to them. Still, Adoulla took enough time now to give the fraud a long, scornful glance. They knew Adoulla, these men, knew him to be the last of the real thing—was it wrong that he took some pride in that? This one, at least, had the decency to lower his eyes in shame.

That such thieves thrived was sad, but it was the way of the world. Adoulla passed the fraud by, spitting at the man’s feet instead of throwing a punch as he once would have. The fool made an offended noise, but that was all.

By the time he reached Miri’s tidy storefront it was past midday. The brassbound door was open and, standing in the doorway, Adoulla smelled sweet incense from iron burners and camelthorn from the hearth. For a long moment he just stood there at the threshold, wondering why in the world he’d been away from this lovely place so long.

A corded forearm blocked his way, and a man’s shadow fell over him. A muscular man even taller than Adoulla stood scowling before him, a long scar splitting his face into gruesome halves. He placed a broad palm on Adoulla’s chest and grabbed a fistful of white kaftan.

“Ho-ho! Who’s this forsaker-of-friends, slinking back in here so shamelessly?”

Despite all his dark feelings, Adoulla smiled. “Just another foolish child of God who doesn’t know to stay put, Axeface.” He embraced Miri’s trusted doorman, and the two men kissed on both cheeks.

“How are you these days, Uncle?” the frighteningly big man asked.

“Horrible, my friend. Horrible, miserable, and terrible, but we praise God anyway, eh? Will you announce me to Miri, please?”

Axeface looked uncomfortable, as if he was considering saying something he didn’t want to say.

“What is it?” Adoulla asked.

“I’ll announce you, Uncle, and there’s not a man in the world I’m happier to see pay the Mistress a visit. But she isn’t gonna be happy to see you. You’re lucky her new boyfriend isn’t here.”

Adoulla felt his insides wither. For a moment he had no words. “Her… her… what ?” he finally managed. “Her who ?” He felt as if he’d suddenly been struck half-witted.

“Her new man,” Axeface said with a sympathetic shake of the head. “You know him, Uncle. Handsome Mahnsoor, they call him. Short fella, thin moustache, always smells nicer than a man should.”

Adoulla did know the man, or at least knew of him. A preening weasel that twisted others into doing his work for him. Adoulla’s numbness burned away in a flame of outrage.

“ That one!? He’s too young for her! Name of God, he’s clearly after her money!” He gestured with one hand to the greeting room behind Axeface. “The son of a whore just wants to get his overwashed little hands on this place. Surely, man, you must see that!”

Axeface put up his leg-of-lamb-sized hands as if frightened of Adoulla. “Hey, hey, Uncle, between you and me, you know I love you. You’d make a great husband for the mistress. But you’ve made some damned-by-God stupid choices far as that goes. Surely, man, you must see that , huh?” Axeface poked him playfully, but Adoulla wasn’t in the mood.

At all.

Seeming to sense this, Axeface straightened to his full, monstrous height. “Look, Doctor, the bottom line is, I don’t see nothin’ Mistress Miri don’t want me to see. That’s how I stay well-paid, well-fed, and smiley as a child. But if you want to see the Mistress, hold on.”

Adoulla was announced and ushered into the large greeting room. Scant sunlight made its way through high windows. Tall couches lined the wall opposite the door, and a few well-dressed men sat on them, each speaking to a woman.

Then she was there. Miri Almoussa, Seller of Silks and Sweets. Miri of the Hundred Ears. Miri. Her thick curves jiggled as she moved, and her worn hands were ablaze with henna.

“What do you want?” she asked him, a cold wind blowing beneath her words.

Adoulla’s irritation briefly eclipsed his longing. “You may recall, woman, that you asked for my help, even after your having asked me to ‘walk my big feet out of your life and never come back.’ But this is not the place for us to speak.”

Miri arched an eyebrow and said nothing, but she led him to the house’s tiny rear courtyard, sat him down at a small table, and brought him a tray with fruit nectar, little salt fish, and pickles. She sat down beside him and waited for him to speak. But for a moment Adoulla just sat there, listening to the birds chirping in the courtyard’s twin pear trees and avoiding Miri’s eyes.

He didn’t break the silence until Miri began to tap her silk-slippered foot impatiently. “I’m here, Miri, because I have learned something of your niece’s killers. But not enough yet to stop them from killing others. I would like to speak to your grandnephew again, as he may have recalled something new.”

“Faisal is not here. Some of the girls went on a workbreak trip to see the new menagerie the Khalif has set up outside the city, and I thought it a good idea for him to try and forget his pains, so I sent him with them. He won’t be back for a day or so.”

Adoulla plucked up a pickle and smiled to himself at the thought of a whores’ holiday to see strange beasts—surely Miri was the only proprietor in the city who would allow such a thing.

As happened so often, Miri seemed to read his thoughts. She did not seem amused. “All people who work deserve days away from their labor, Doullie,” she said flatly. “And whores are people, even if my business depends on letting men forget that fact.”

He would not rise to the bait. “Of course. In any case, I did not come only to speak to Faisal. I came also because Miri’s Hundred Ears are always open, sometimes to songs the rest of us don’t hear. For instance, does the name ‘Mouw Awa’ mean anything to you? Or the name ‘Orshado’? And what do you know of the case of Hadu Nawas?”

Читать дальше