Dawoud encouraged him. “With apologies for knowing that which I ought not, Captain, I have heard that there is… tension between the guard and the watch.”

Roun spoke half to himself. “Look, in every city there will be watchmen who harass blacksmiths’ daughters and knock down old men for a few coins or a laugh. But there is cruelty and there is cruelty . There is corruption and there is corruption . People can no longer afford to pay the taxes we’re asking. Too many are finding their way into the gaol. Far too many. And every debtor imprisoned, even for a fortnight, is a recruit for that preening traitor Pharaad Az Hammaz!”

“Indeed,” Dawoud agreed.

“And then there is the thief-purging. Here in the palace matters legal and martial fall to me. But in the streets the captain of the watch rules, and he was appointed because he has never in his life balked at a chance to bully. This new drive to wipe out pickpocketry is madness. There will be a lot more one-handed men in Dhamsawaat before it’s through. The last amputation I saw was of a boy of ten years. But at least the boy only lost his hand! Too many men have been made to kneel on the executioner’s leather mat of late.”

“Aye,” Dawoud said. “I’d heard about the boy who was to be executed before the Falcon Prince—”

Roun’s expression turned dangerous. “The bastard’s name is Pharaad Az Hammaz, Uncle! He’s not a Prince! Anyway, incidents like that are driving good men away from the guard and the watch. A fortnight ago my second-in-command, Hami Samad—a man born and raised in this palace, and as steadfast a man as I’ve ever met—left the guard, abandoning his duties without saying a word to anyone.” Roun knuckled his moustache and sighed, fatigue overtaking his features.

“Well, I am sorry to have added to your troubles. The Khalif was not happy with you for bringing me before him.”

Roun waved a dismissing hand at Dawoud’s apology, but there was real worry in the captain’s eyes. He frowned, and his brow knitted even tighter. “What is going on, Dawoud? Whatever the Khalif’s flatterers think, I know you would not be here if there was not dire reason.”

“And there is, my friend. The servants of the Traitorous Angel are at work. But I don’t know much more than the little I’ve told you. As soon as I learn more I will let you know, Captain, I swear it.”

Roun gave him a long look. “Very well, Uncle. Just be sure that you do. And I’ll set my street spies a-digging at these names and crimes you’ve told me of. I am always here at the Palace, so when you wish to speak to me again, just have a guardsman summon me.”

Dawoud exchanged cheek-kisses with the Captain, then made his way back to the street. Pain raged in his muscles and bones. Too much bowing and walking. He needed rest and, more than anything on God’s great earth, he needed to see his wife again. I could have died in there on a fool’s whim .

Dawoud thanked Almighty God aloud that he lived. Then he achingly made his way home.

Walking down Breadbakers’ byway, Adoulla passed a public fountain of once-white marble. Children played in its basin, and their shrill shouts shoved their way into his ears. “Brats,” he huffed to himself, though he knew he’d been twice as loud and obnoxious when he was a street child.

To save one child from the ghuls is to save the whole world. The professional adage came to Adoulla for the thousandth time. But what would it cost to save the whole world? His life? O God, does not a fat old man’s happiness matter, too?

This fight had already cost him his home. The place that he had loved so for so long was ruined. Vials of powdered silver and blocks of ebonwood. The Soo sand-painting he’d bought in the Republic, and the Rughali divan that fit his backside so comfortably. But most of all, the books! Scroll and codex, new folio and old manuscript. Even a few books in tongues he’d once hoped to learn—leatherbound volumes in the boxy script of the Warlands to the far west. He’d only ever managed to learn to read a few of their strange, barking words. Now he’d never learn more.

He moved against the onrushing flow of foot traffic, making his way over the smooth, worn stones of the Mainway. He was comfortable moving against the crowd. How many times had a mob of sensible men been running away from some foul monster while foolish Adoulla and his friends ran toward the thing? Irritated anew at the thought of the things his calling made him do, he pushed his big body grumpily up the downstream of people.

Another pack of children chased each other through the crowd of walkers and pack animals. The little gang threatened to careen into Adoulla, but the group split before him like a wave, half the brats flowing to either side. He reminded himself that, if he didn’t do his duty, more little faces like these could soon be smeared with blood, their eyes aflame and their souls stolen. In his practiced way, he kept panic from rising at the thought of the threats that were out there, unseen.

Adoulla passed men from Rughal-ba, with their neatly trimmed goatees and tight-fitting turbans. He saw Red River and Blue River Soo. He heard the false promises of a hundred hawkers, the single-stringed fiddle of a roving musician, the argument a feral-eyed, twitching man was having with himself. Unlike most sons of Dead Donkey Lane, Adoulla had seen many towns. Those folk he’d grown up around would leave the city only a handful of times in their lives—even going to another quarter was an occasion for some of them. Adoulla, on the other hand, had seen the villages of the Soo Republic with their low, bleached-clay houses of hidden luxury. He had seen the strange mountain-hole homes of the far north, where rain froze. He’d been to the edge of Rughal-ba, where, instead of being a character from lewd shadow-puppet plays, the ghul hunter was respected by powerful men as an earthly agent of God, and was considered a slave of the Rughali High Sultaan—if a rich and powerful slave.

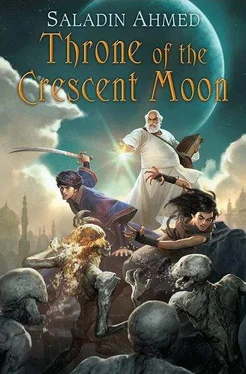

But this city of his—his for some sixty years—well, there was nothing to compare with its streets. The crowds had annoyed Adoulla all his life. But of all the places in the Crescent Moon Kingdoms he had been, Dhamsawaat alone was his . And somewhere in his city, murderous monsters were preying on people.

And so, you old fart, Dhamsawaat needs you. Rotating this truth proudly in his mind made Adoulla feel just a little bit less tired. But as his sandaled feet brought him closer and closer to the house of Miri Almoussa, his fatigue returned twofold.

True to the code of the ghul hunter, Adoulla had never married. When one is married to the ghuls, one has three wives already, was another of the adages of his order. He didn’t know much about the old order—a few adages and invocations passed down many years ago by his teacher, old Doctor Boujali, and learned from old books. The ghul hunters had never been as cohesive a fraternity as the Dervishes’ Order—and any man could wear white and claim to chase monsters. Still, over the years, Adoulla had tried to adhere to what he had learned of the ways of his ancient order. He was a permissive man in many ways—no less with himself than with others, he had to admit. But in some things rigidity was the only way. Saying marriage vows before God would cause a ghul hunter’s kaftan to soil, and it would cost him the power of his invocations. As with so many of God’s painful ways, Adoulla did not know why it was so, only that it was .

The crowd thinned and Adoulla strode through Little Square, his kaftan billowing in the breeze. Little Square was not little at all—in fact, in all the city it was second only to Angels’ Square in size. But the name was old, from the days when Dhamsawaat had first been built on the ruins of a Kemeti city, and had only had two squares. Long rows of brown, thorny shrubbery framed its eastern and western sides. These low, desert bushes served as a back wall for the stall-less, beggarish sellers who lined the square to Adoulla’s left and his right.

Читать дальше