The vision of his disappearance had come clear to Tayba and to Skeelie, to the Seers who had stayed behind. Ram might return as abruptly as he had disappeared, but somehow the sense of his going seemed, to those Seers who had viewed it, one of terrible finality.

Jerthon knew that Tayba was not among the crowd, that she stood alone in the tower, in the solitude of her room—reaching out in vain toward Ram, across time she could not manipulate. Reaching out, and sorrowing, unable to touch him.

Had Ram been sucked into Time by powers yet unimagined? Or had he only, mourning for Telien, thrown himself into that maelstrom in search of her? Even with the vision of his going that had come so clear to them, the sense of Ram’s feelings was not clear. All had happened too fast: an instant when Ram faced Anchorstar, an instant when it seemed he clung to Telien somewhere, and then he was gone.

Jerthon dismounted, left his horse to another to care for, and went up into the tower. Tayba would need him. She would be drawn tight inside herself and short with him in her grief over Ram; but she would need him now. He could not think what to say to her. But that did not matter.

Gone. Ram gone. He shook his head, trying to drive out the nightmare, but it would not go. Gone into Time. Had Ram found Telien in some realm so remote from this time that one could hardly imagine it? And did Telien have a shard of the stone, could the two of them, perhaps, with the power of the stone, yet return to their own time?

Or would they, foolish, young—valiant—try to seek out the rest of the stones across a warping vastness of Time that no man could truly comprehend? He came up the third flight and stood before Tayba’s door, knew she was pacing. He knocked, heard her answer with muffled annoyance.

He found Tayba pacing, and Skeelie there, worn from battle, from her swift journey home, kneeling before an old chest rummaging, muttering, her shoulders hunched beneath stained fighting leathers, her face, when she turned to look at him, pale with loess dust from the ride out of the north, her eyes haunted with the knowledge of Ram’s loss. She said nothing, would not meet his eyes, was strung tight with the agony of her loss—loss to Time as well as to Telien. At last she pulled out a cloak of heavy wool from the chest, closed the lid, and sat back on her heels, lowering her eyes before him, then looking up at him suddenly and defiantly. “I am going there. I am going into the mountains, and please don’t argue. To the caves of Owdneet first, to find runes I think can . . . can lead me. Can take me into Time, can . . . I will not rest until I have done this.” And, seeing his scowl, “Please don’t argue, Jerthon.”

He looked at the two of them. Had Tayba encouraged Skeelie in this? No, he thought not. Skeelie’s need was plain. Despite Ram’s love for Telien, she would save him.

“What makes you think that in the caves—that you can find anything to help you?”

“I . . . when Ram and I were in the great grotto, when we were children, we . . . Fawdref showed us with his thoughts that there were caves there that held the old tablets and runes of the ancient city. There were powers written there, Jerthon. Powers lost to us.”

“But powers of the gods, Skeelie. You can’t . . .” He knew he argued uselessly. He would keep her here if he could, and knew she would not stay.

“Powers any Seer can use, Jerthon. If one is willing to seek them, willing to try them, to risk . . .”

“Yes. To risk death. Or worse than death.”

She stared at him, defying him, her thin face drawn, her dark eyes large with anguish, as she had looked so often as a child. “You know I must go, and arguing only makes it harder.” She rose to stand before him, hugged him suddenly in a terrible embrace, clung to him for a long moment. Hugged Tayba with more tenderness, then fled, turning at the door only to say, “I will come to you when I am ready to leave. Meanwhile—take care of her, Jerthon. Care gently for one another.”

*

Skeelie rode out for the mountains early the next dawn, accompanied by the older Seer Erould. He would bring her horse back. Would, before he returned home, ride into Kubal as a trader. That had been Jerthon’s idea, to know what was happening in Kubal. ‘To be sure they are not strengthening again. Erould, you crusty old dog,” Jerthon had said, grinning, “you look the part of a trader. Tousle your hair, don’t bathe. You’ll do very well as a trader.”

Skeelie and Erould rode in silence through the gray dawn up along the sea then along the river Somat Cul. Skeelie looked up toward the mountains rising ahead of them and saw, in her mind, the shadows of wolves, then the shape of the grottoes of Owdneet. She pushed her horse faster, impatient to get on. And grown impatient, suddenly, of company, too, of conversation. Though she should be thankful for Erould’s presence, for this last warm link with men familiar, men of her own time and her own kind. But she could not make conversation in spite of needing human warmth, she mourned Ram too much.

If Telien were dead—but she put that thought from her. She would save Telien, she loved Telien in a strange, puzzling way. Because of Ram, she supposed, though it made no sense to her. Jealous, pained at Telien’s existence, yet she would care tenderly for her, would bring them both home, and gladly, if ever she could search them out.

Erould, his mind politely closed to her misery, pulled his cap down over his dark grizzled hair, then waved an arm to encompass the pale loess hills to the north. “Won’t be long, all this will be settled. Farms, a little town. Now the Pellian Seers are dead, the Hape. Oh, we will build, Skeelie. Grow crops—men will come from all over Ere, craftsmen, breeders of fine stock . . .”

She didn’t want to answer. Just let him keep talking. The sound of his voice was good, tying her to this time for a little while yet, tying her to warmth and human feeling—pushing away her fear of the unknown that she would soon face. Making her know that no matter where she was, in what dark reaches of Time, yet here in this time Carriol would be safe, would be filled with the joy of its growth.

And Ram might never see it. Would miss it all, the joyful work and growth. Ram. Ram. You loved it so—this time, this lovely land.

Erould watched her, touched her mind, then, in spite of himself, and drew back pained with her pain, driven for a moment as she was driven, desperate in her mourning and need; so painful were her thoughts that he wished—not for the first time—that he had not the skill to touch another’s mind. He knew where she was headed and why, mourned for her, was distressed for her, and could do nothing. He would not see her again in this life, he felt suddenly certain. He took pains to hide that thought from her. They came to Blackcob at noon, made a brief greeting, a brief meal, and went on. Skeelie had begun to grow nervy, her fear taking hold, thoughts of turning back beginning to rise unbidden. They rode in silence up along the Urobb, and that night camped in the lee of the dark mountains; the next day they followed a goat trail so narrow and with so steep a drop beside it, it made them both nervous. Erould left her at last in mid-afternoon at the foot of the peak where lay the grotto of Owdneet, swung away leading her horse down in the direction of Kubal, left his good will with her and his prayers and did not look back.

Skeelie watched him go and swallowed. She stared down over the land, the lovely land. The hills above Burgdeeth and Kubal were blackened, scarred; but they would be green again. Even in a few weeks, she knew, the green would begin to come. In the far distance a gray smear showed the outline of Carriol’s cliffs and the ruins; and the sea was a bright streak in the dropping sun. Lovely. She bit her lip. Would she see all this again?

Читать дальше

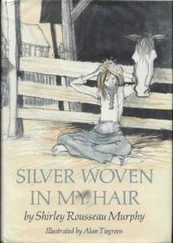

![Ширли Мерфи - The Shattered Stone [calibre]](/books/436059/shirli-merfi-the-shattered-stone-calibre-thumb.webp)