Dedication

To the memory of Bobby Long

Contents

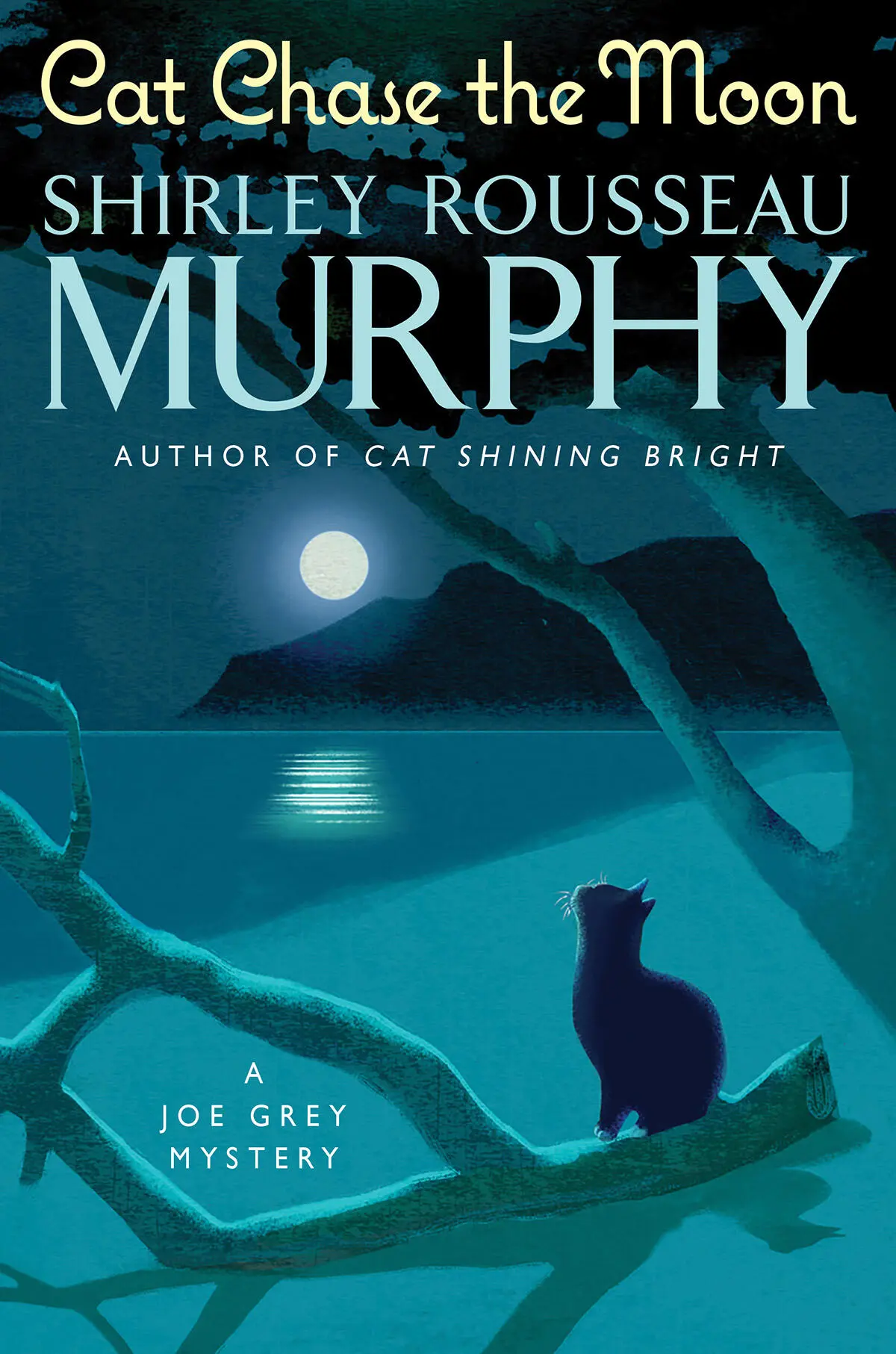

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

About the Author

Also by Shirley Rousseau Murphy

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

The old man didn’t want to wake up, he didn’t want to get out of bed, he felt so heavy he longed only to drop back into sleep. Through the curtain of the east window the first smear of fog-dimmed sun sulked lifeless and depressing. Even the hens outside sounded dreary, as if they had no desire at all to lay an egg or peck at the scattered grain. The world was without joy, no smallest pleasure awaited him, no sound of Mindy running and laughing and talking to her pony, or galloping across the field.

It was two weeks since her parents had left, taking the child with them, taking his little granddaughter away to live in town, Mindy shouting, “I don’t want to go! You can’t make me go,” crying so hard she nearly threw up. But of course they had taken her. Mindy was a brat when she was around her parents. She was nice as pie when she was just with him, or with her pony; she was full of life and fun. Why couldn’t Nevin and Thelma have left her here? Now, every day, every hour that she was gone the emptiness grew worse. He’d thought it would get better, but it hadn’t. No more than two weeks earlier he had begun to come to terms with Nell’s death. Then the last of their three grown sons left so soon after his mother’s funeral, taking Zeb’s only grandchild away and not giving a damn if he was alone, never caring if he was still filled with pain over Nell’s passing, never caring if Mindy might have been a solace to him. Never even wondering if he could manage the farm without a little help from Mindy.

Well, at least Nevin, his youngest, and his wife, Thelma, had waited until Nell was gone, they hadn’t hurt Grandma like Varney had, his middle son leaving six months ago, walking out on Nell while she was so sick. (Ever since Mindy was born, all three grown boys called their mother Grandma.) Varney said he’d gotten a job in town, one too good to refuse. He didn’t say what kind of job and Zeb didn’t ask. Varney hadn’t cared that he was breaking his dying mother’s heart. Maybe her hurt over Varney’s abandonment had made the cancer worse, Zeb would never know. Well, Varney’s leaving hadn’t been so bad in the end. Without his temper the house had been quieter for Nell.

But then his Nell died, of the pain and cancer or maybe of the medicine itself, how could anyone know? As soon as she was buried, Nevin and Thelma packed right up and moved into the village and never asked if Mindy could stay here with him. Mindy, with her curly brown hair, brown eyes, and turned-up nose, was twelve, bright and loving, and she was all he’d had left. Thelma might have let Mindy stay but she was too scared of Nevin to disobey him. Zeb and Nell had been married fifty years and just the one grandchild, and now suddenly everyone was gone. Zebulon Luther was alone.

Fifty years of marriage, a happy marriage. But as soon as his Nell passed, after all the illness, the last boy hauled out. Left Zeb when he wasn’t so well, either, with the arthritis and the kidneys. Left him to do for himself, cook, keep up the garden and farm work, though there wasn’t much of that anymore. He’d stopped haying some years back, when he was in his sixties. The two younger boys wouldn’t hay, they had let the land go to weeds not even fit for pasture. And DeWayne, his oldest, had never taken to farming. He liked the city life, he liked to travel. Zeb didn’t know how he made his living, he wondered a lot about that, but Zebulon seldom saw him.

Well, at least he had the two horses for company. But what good was the pony when the child missed him, and the pony missed her. “You can’t keep a horse in town!” Thelma had mocked when Mindy begged. And the pony without Mindy was growing as lifeless and sad as Zeb himself.

Earlier this morning, before dawn, something had waked him; or maybe he was dreaming that cold eeriness, the moon drowning in thick fog above a battered body that lay struggling in an open grave; and above it stood the shadow of a big tomcat. He lay half awake and puzzled; but the dream faded and was gone. Shivering, he pulled the quilts up and crawled back into sleep.

1

The sea crashed behind Joe Grey, the tomcat standing tall on a heap of broken branches; the night’s heavy fog admitted only a smear of light from the low moon, just enough to brighten the hushing waves. The sound of digging had drawn the gray tomcat up the beach to the little sandy park, to the oak tree that had long ago fallen, a dry and twisted relic from last spring’s storms. The shoveling noise stopped abruptly when Joe Grey inadvertently stepped on a twig: a sudden silence cut the night, then the sound of running through the sand and dry grass among the scattered trees.

He couldn’t see much of the runner in the heavy mist and tangled branches but he could tell it was a man, heavy footfalls among the dead branches. He could see dark clothes, a dark floppy hat, brim pulled down. Joe heard him hit the sidewalk, hard rubber-soled shoes, heard a car door open. Heard an engine start and the car pull away, a dark, long shadow in the mist. Joe leaped to the highest branch of the fallen tree, looked down where the man had been digging.

A body lay beside the dead tree where dirt had been scooped out. A half-dug grave in which a woman lay nearly buried, bruised and bloodied, fresh earth thrown over her lower body and legs—but she couldn’t be dead, blood still flowed, her heart would still be beating.

At the edge of the grave, in the damp, heavy sand, he could see the shovel marks, small, sharp curves in the shape of those spades people carried in their cars for an emergency.

She was slim and tall, her long black hair was tangled but, except for the blood, clean and shining. She would be beautiful under the purple bruises across her face and what looked like purple finger marks circling her throat. Her right earring was missing, the lobe torn sharply in two: the two ragged flaps bleeding down her white shirt. Her left ear was red and bloody, swollen around a lump of smashed gold, as if the side of her head had been pounded against a log. Flecks of bark clung to her face.

Dropping down from one fallen branch to the next, Joe Grey stepped into the half-dug grave and put his nose to her mouth. Yes, the faintest breath.

He pushed his mouth to hers, feeling weird at the contact; he breathed in and out, forcing air into her lungs until her gasping came stronger. Her right hand moved faintly. The tomcat, even after the dead bodies he had confronted at so many crime scenes, felt sick that the grave digger had meant, apparently, to bury her alive.

A patrol car passed slowly, making its rounds. The fog was so thick the officer didn’t see a thing among the tangled tree branches nor would he have heard any strangled cry, over the static of his radio. As the unit passed, Joe considered yelling out for help.

Right, and have the guy’s strobe light catch him, a tomcat, yelling “Help!” and then running. Worse, Joe knew most of the officers and they knew him, dark gray tomcat, white paws and thin white strip down his gray face. He was in and out of the station all the time, was practically the station cat. For a cop to see him here on what would turn out to be a crime scene wasn’t smart. One more puzzle for the department, Joe Grey nosing around a crime scene at just about the time the “phantom snitch” called in the report—if he could find a phone. His presence here would be one more coincidence he didn’t need. He prayed that Haley would pull over, get out of the car, find the half-buried victim himself and call the dispatcher—while Joe fled among the rubble of the wild little park and vanished.

Читать дальше

![Ширли Мерфи - The Shattered Stone [calibre]](/books/436059/shirli-merfi-the-shattered-stone-calibre-thumb.webp)