CHAPTER 1

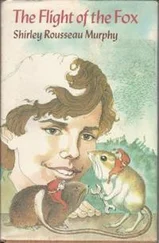

A young girl sleeps in a small, drab room. In her dream she watches the surf beat against a rocky cliff, filling the tide pools and casting spray to the meadows above.

Far away a small buckskin horse lifts his head and listens in vain for the pounding of the sea.

The room is still and very dim. There is only one window, facing a light well, a brick-lined shaft down which little of the dawn can come. The noise and shouting in the apartment have subsided and the bedroom door is locked from inside.

The room has not cooled off during the night, but still holds the stale heat of yesterday, and the two children sleep with only sheets over them, the boy tossing fitfully. They are children too old to be sharing a room, but share they must, for there is no other, except their aunt and uncle’s, and a small ugly sitting room and a kitchen like the inside of a brown box. The whole apartment is like this, the wallpaper used and dirty looking, the ceiling paint colorless with grime, the windows small and unwashed, the carpets and furniture unpleasant to sit on and touch.

In Karen’s dream the sun is bright. She is sitting astride the buckskin horse, watching the pasture grass blow and listening to the crash of the surf. The horse tosses his head, and in her sleep Karen smiles a little and her lashes move softly on her freckled cheeks.

She is well freckled. Both children are. Like flecks of gold the freckles spatter their noses and cheeks, the only brightness in the room. She is older than Tom by a year, but he is taller. They are twelve and thirteen.

“I could pass for sixteen. So could you. We’re tall enough. We could get jobs,” was the last thing she had said before she went to sleep, the door bolted against the drunken shouting of their uncle.

Yes, we’re tall enough, Tom had thought. Maybe we could. He had reached to check the lock on the door, then fallen asleep himself almost at once.

It had started early the previous morning, with Uncle George pouring whisky into his coffee. The children had gulped their breakfasts and got out into the street, but at noon hunger had forced them back again. “It’ll be awful,” Karen had said. It was. They could hear their uncle and aunt shouting before they got near the door, and as the children slipped down the hall to the kitchen the dim apartment was nearly unbearable with the smell of whisky.

There was more shouting as they hurriedly gathered together peanut butter and bread, milk and glasses, and a knife.

“You shouldn’t hear words like that,” Tom said.

“And what about you?”

“But you re a girl.”

“Doesn’t matter,” Karen said. “Come on.” As they ate, staring out the dirty window at the brick wall, trying to ignore the shouting, they talked, as they had so many times, about what to do.

There were only three things. The first was to run away, and this was the most attractive. Now that school was out their need was greater than ever; and it would be easier.

The second thing was the most sensible. “But what would they do with us if we did go to the authorities?” Karen said. They were afraid to find out.

The third thing, of course, was to stay where they were and make the best of it until they were old enough to leave. Eighteen was forever. “Like trapped animals,” Karen said.

The delight of running away haunted them. Summer lay outside the city, summer and fields and freedom. But they weren’t stupid children. There was everything against its working.

“They would find us,” Karen said.

“Maybe not,” Tom answered.

And if they were found, what then? Who would find them? Not Aunt and Uncle, surely; they wouldn’t care. Then it would be the authorities. Would they put them in a home for orphans? Separate them? Or would the children be put up for adoption, each going to a different family? “A different city, likely,” Karen said. “They might make it worse for us, worse than if we went to them right off.”

Tom thought it wouldn’t make any difference. “They’d see we couldn’t stay here. Someone would understand.” Tom had more faith in people than Karen did. Karen had little faith in anyone any more, except Tom and herself.

It had been harder for her than for him. She is a girl, and softer, Tom thought, though he knew that she could stand some things better than he. Still, the last year had been harder on her. She seemed to draw strength from the country and the sea, and had needed these things, and her pony, badly those first weeks after their parents had been killed so suddenly. When the children had been moved to the city she had grown pale and listless.

After the funeral the children had hoped they could stay on the farm; no one would know, or care. But this was not the case. Somehow, what they thought right didn’t seem right to anyone else. The farm had been sold, and worse, so had the four horses, who were all that was left from their life with Mother and Dad, all that was left of their childhood, it seemed.

Karen missed Kippy so badly that sometimes at night she thought she could put out her hand and feel his soft gold neck and his tangled black mane. No one would tell the children where the horses were, and Karen still cried for them, in a way quite different from the way that she cried for Mother and Dad. Their parents were dead, and there was a huge empty spot in the middle of Karen that would never go away; but she knew she would see them again at the end of everything, a long way off. It was like looking down a dim tunnel to something brilliant at the other end.

She cried for the horses because they could be hungry, hurt, all the things living creatures can be. She thought that she and Tom were the only ones who would help them, who would care.

In her dream she rides Kippy, galloping, along the cliff above the sea, the wind blowing salty spray in her face, Mother following on her chestnut mare, then Tom and Dad, Dad’s big bay bucking a little and Tom’s mare, Tolly, shying at rabbits.

Karen is smiling as she wakes, but instead of sunshine, here is the dismal room, and the empty hurt to engulf her once more. The picture on the dresser is all that is left of that life—the big house standing comfortably between the willows, facing the sea, the family mounted, the horses looking eager.

Karen closes her eyes and curls tight under the covers. She wishes she would die, but she knows you do not die of unhappiness, and she thinks back to the day of the funeral. It was a cold, blustery day, and there seemed to be a great deal of black—the hearse, the strange pallbearers; somehow all the flowers meant nothing. She was glad it was cold, that the wind blew. Even the pastor’s face did not seem real. He talked to her for a long time after the funeral, when Tom had gone off by himself. She did not listen to him at first, but as he talked she began to listen. “There are things you must do for your parents now, Karen,” the pastor repeated. Karen did listen to this. “You are the measure of their lives now,” he continued. “If you were to give up living you would kill something belonging to them. What you do with your life, Karen, will be the proof of their worth as well as your own.” He paused, looking at her. “Will you disappoint them?”

She knew she would not. Nor would Tom.

She dozes again, and when she wakes the room is lighter and the uncle’s yelling has started once more. The language is vile. Tom is awake, too, sitting by the window spreading peanut butter on a slice of bread. He hands it to her and spreads another. The musty smell of the room makes the peanut butter taste stale, but it fills a little bit of Karen’s empty stomach, and after three slices of bread she gets up to wash and dress. She hates going out into the hall, and makes Tom lock the door behind her and wait for her soft knock.

Читать дальше

![Ширли Мерфи - The Shattered Stone [calibre]](/books/436059/shirli-merfi-the-shattered-stone-calibre-thumb.webp)