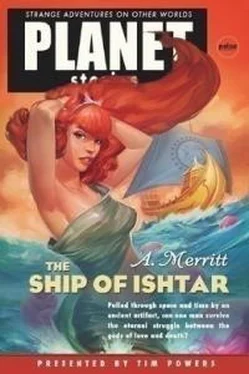

Абрахам Меррит - The Ship of Ishtar

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Абрахам Меррит - The Ship of Ishtar» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2014, Издательство: epubBooks Classics, Жанр: Фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Ship of Ishtar

- Автор:

- Издательство:epubBooks Classics

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Ship of Ishtar: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Ship of Ishtar»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Ship of Ishtar — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Ship of Ishtar», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"He cannot drive me out of Sharane's heart!" Kenton cried.

The Viking bent his head down to the compass.

"You may be right," he muttered. "Zubran may be right. All I know is that while your woman is faithful to Bel, no man may harm her!"

Vague as he might be on that one point, the Viking was direct and full of meat upon others. The Norseman had been observant while slave to the priests of Nergal. He knew the city and the Temple of the Seven Zones intimately. Best of all he knew a way of entering Emakhtila by another road than that of its harbor.

This was indeed all important, since it was not within the bounds of possibility that they could enter that harbor without instant recognition.

"Look, comrades," Sigurd scratched with point of sword a rude map on the planks of the deck. "Here lies the city. It is at the end of a fjord. The mountains rise on each side of it and stretch in two long spits far out to sea. But here"—he pointed to a spot in the coast line close to the crotch where the left hand mountain barrier shot out from the coast—"is a bay with a narrow entrance from the sea. It is used by the priests of Nergal for a certain secret sacrifice. Between it and the city a hidden way runs through the hills. That path brings you out to the great temple. I have traveled the hidden way and have stood on the shores of that bay. I went there with other slaves, bearing priests in litters and things for the sacrifice. While it would take two good sleeps for a ship to make the journey from Emakhtila to this place, it is by the hidden way only half so far as a strong man could walk in my own land between the dawn and noon of a winter day. Also there are many places there where the ship can be hidden. Few galleys pass by and no one lives near—which is why the priests of Nergal picked it.

"Also I know well the Temple of the Seven Zones—since long it was my home," went on Sigurd. "Its height is thirty times the ship's mast."

Kenton swiftly estimated. That would make the temple six hundred feet—a respectable height indeed.

"Its core," said the Viking, "is made up of the sanctuaries of the gods and the goddess Ishtar, one upon each other. Around this core are the quarters of the priests and priestesses and lesser shrines. These secret sanctuaries are seven, the last being the house of Bel. From Bel's House a stairway leads up into his Bower. At the base of the temple is a vast court with altars and other shrines where the people come to worship. Its entrances are strongly guarded. Even we four could not enter—there!

"But around the temple, which is shaped thus"—he scratched the outline of a truncated cone—"a great stone stairway runs thus"—he drew a spiral from base to top of cone. "At intervals, along that stairway, are sentinels. There is a garrison where it begins. Is this all clear?"

"What is clear," grunted Gigi, "is that we would need an army to take it!"

"Not so," the Viking answered. "Remember how we took the galley—although they outnumbered us? We will row the ship into that secret harbor. If priests are there we must do what we can—slay or flee. But if the Norns decree that no priests be there, we will hide the ship and leave the slaves in care of the black–skin. Then the four of us, dressed as seamen in the clothes and the long cloaks we took from the galley, will take the hidden way and go into the city.

"For as to that stairway—I have another plan. It is high walled—up to a man's chest. If we can pass without arousing the guards at its base, we can creep up under shadow of that wall, slaying the sentinels as we go, until we reach the Bower of Bel and entering, bear Sharane away.

"But not in fair weather could we do this," he ended. "There must be darkness or storm that they see us not from the streets. And that is why I pray to Odin, that this brewing tempest may not boil until we have reached the city and looked upon that stairway. For in that storm that is surely coming we could do as I have said and swiftly."

"But in all this I see no chance of slaying Klaneth," growled Zubran. "We creep in, we creep up, we creep out again with Sharane—if we can. And that is all. By Ormuzd, my knees are too tender for creeping! Also my scimitar itches to scratch itself on the black priest's hide."

"No safety while Klaneth lives!" croaked Gigi, playing upon his old tune.

"I have no thought of Klaneth now," rumbled the Viking. "First comes Kenton's woman. After that—we take up the black priest."

"I am ashamed," said Zubran. "I should have remembered. Yet in truth, I would feel easier if we could kill Klaneth on our way to her. For I agree with Gigi—while he lives, no safety for your blood–brother or any of us, However—Sharane first, of course."

The Viking had been peering down into the compass. He looked again, intently, and drew back, pointing to it.

Both the blue serpents in the scarlet bath were parallel, their heads turned to one point.

"We head straight to Emakhtila," said Sigurd. "But are we within the jaws of that fjord or out of them? Wherever we are we must be close."

He swung the rudder to port. The ship veered. The large needle slipped a quarter of the space to the right between the red symbols on the bowl edge. The smaller held steady.

"That proves nothing," grunted the Viking, "except that we are no longer driving straight to the city. But we may be close upon the mounts. Check the oarsmen."

Slower went the ship, and slower, feeling her way through the mists. And suddenly they darkened before them. Something grew out of them slowly, slowly. It lay revealed as a low shore, rising sharply and melting into deeper shadows behind. The waves ran gently to it, caressing its rocks. Sigurd swore a great oath of thankfulness.

"We are on the other side of the mounts," he said. "Somewhere close is that secret bay of which I told you. Bid the overseer drive the ship along as we are."

He swung the rudder sharply to starboard. The ship turned; slowly followed the shore. Soon in front of them loomed a high ridge of rock. This they skirted, circled its end and still sculling silently came at last to another narrow strait into which the Viking steered.

"A place for hiding," he said. "Send the ship into that cluster of trees ahead. Nay—there is water there, the trees rise out of it. Once within them the ship can be seen neither from shore nor sea."

They drifted into the grove. Long, densely leaved branches covered them.

"Now lash her to the tree trunks," whispered Sigurd. "Go softly. Priests may be about. We will look for them later, when we are on our way. We leave the ship in charge of the women. The black–skin stays behind. Let them all lie close till we return—"

"There would be better chance for you to return if you cut off that long hair of yours and your beard, Sigurd," said the Persian, and added: "Better chance for us, also."

"What!" cried the Viking, outraged. "Cut my hair! Why, even when I was slave they left that untouched!"

"Wise counsel!" said Kenton. "And Zubran—that naming beard of yours and your red hair. Better for you and us, too, if you shaved them both—or changed their color."

"By Ormuzd, no!" exclaimed the Persian, as outraged as Sigurd.

"The fowler sets the net and is caught with the bird!" laughed the Viking. "Nevertheless, it is good counsel. Better hair off face and head than head off shoulders!"

The maids brought shears. Laughing, they snipped Sigurd's mane to nape of neck, trimmed the long beard into short spade shape. Amazing was the transformation of Sigurd, Trygg's son, brought about by that shearing.

"There is one that Klaneth will not know if he sees him," grunted Gigi.

Now the Persian put himself in the women's hands.

They dabbled at beard and head with cloths dipped in a bowl of some black liquid. The red faded, then darkened into brown. Not so great was the difference between him and the old Zubran as there was between the new and old Sigurd. But Kenton and Gigi nodded approvingly—at least the red that made him as conspicuous as the Norseman's long hair was gone.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Ship of Ishtar»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Ship of Ishtar» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Ship of Ishtar» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Абрахам Меррит - Лунный бассейн [Лунная заводь]](/books/20623/abraham-merrit-lunnyj-bassejn-lunnaya-zavod-thumb.webp)