In King’s Landing, the first signs of the fatal flush were seen along the riverside amongst the sailors, ferrymen, fishermongers, dockers, stevedores, and wharfside whores who plied their trades beside the Blackwater Rush. Before most had even realized they were ill, they had spread the contagion throughout every part of the city, to rich and poor alike. When word reached court, Grand Maester Munkun went himself to examine some of those afflicted, to ascertain whether this was indeed the Winter Fever and not some lesser illness. Alarmed by what he saw, Munkun did not return to the castle, for fear that he himself might have been afflicted by his close contact with twoscore feverish whores and dockers. Instead he sent his acolyte with an urgent letter to the King’s Hand. Ser Tyland acted immediately, commanding the gold cloaks to close the city and see that no one entered or left until the fever had run its course. He ordered the great gates of the Red Keep barred as well, to keep the disease from king and court.

The Winter Fever had no respect for gates or guards or castle walls, alas. Though the fever seemed to have grown somewhat less potent as it moved south, tens of thousands turned feverish in the days that followed. Three-quarters of those died. Grand Maester Munkun proved to be one of the fortunate fourth and recovered…but Ser Willis Fell, Lord Commander of the Kingsguard, was struck down together with two of his Sworn Brothers. The Lord Protector, Leowyn Corbray, retired to his chambers when stricken and tried to cure himself with hot mulled wine. He died, along with his mistress and several of his servants. Two of Queen Jaehaera’s maids grew feverish and succumbed, though the little queen herself remained hale and healthy. The Commander of the City Watch died. Nine days later, his successor followed him into the grave. Nor were the regents spared. Lord Westerling and Lord Mooton both grew ill. Lord Mooton’s fever broke and he survived, though much weakened. Roland Westerling, an older man, perished.

One death may have been a mercy. The Dowager Queen Alicent of House Hightower, second wife of King Viserys I and mother to his sons, Aegon, Aemond, and Daeron, and his daughter Helaena, died on the same night as Lord Westerling, after confessing her sins to her septa. She had outlived all of her children and spent the last year of her life confined to her apartments, with no company but her septa, the serving girls who brought her food, and the guards outside her door. Books were given her, and needles and thread, but her guards said Alicent spent more time weeping than reading or sewing. One day she ripped all her clothing into pieces. By the end of the year she had taken to talking to herself, and had come to have a deep aversion to the color green.

In her last days the Queen Dowager seemed to become more lucid. “I want to see my sons again,” she told her septa, “and Helaena, my sweet girl, oh…and King Jaehaerys. I will read to him, as I did when I was little. He used to say I had a lovely voice.” (Strangely, in her final hours Queen Alicent spoke often of the Old King, but never of her husband, King Viserys.) The Stranger came for her on a rainy night, at the hour of the wolf.

All these deaths were recorded faithfully by Septon Eustace, who takes care to give us the inspiring last words of every great lord and noble lady. Mushroom names the dead as well, but spends more time on the follies of the living, such as the homely squire who convinced a pretty bedmaid to yield her virtue to him by telling her he had the flush and “in four days I will be dead, and I would not die without ever knowing love.” The ploy proved so successful that he returned to it with six other girls…but when he failed to die, they began to talk, and his scheme unraveled. Mushroom attributes his own survival to drink. “If I drank sufficient wine, I reasoned I might never know I was sick, and every fool knows that the things you do not know will never hurt you.”

During those dark days, two unlikely heroes came briefly to the fore. One was Orwyle, whose gaolers freed him from his cell after many other maesters had been laid low by the fever. Old age, fear, and long confinement had left him a shell of the man that he had been, and his cures and potions proved no more efficacious than those of other maesters, yet Orwyle worked tirelessly to save those he could and ease the passing of those he could not.

The other hero, to the astonishment of all, was the young king. To the horror of his Kingsguard, Aegon spent his days visiting the sick, and often sat with them for hours, sometimes holding their hands in his own, or soothing their fevered brows with cool, damp cloths. Though His Grace seldom spoke, he shared his silences with them, and listened as they told him stories of their lives, begged him for forgiveness, or boasted of conquests, kindnesses, and children. Most of those he visited died, but those who lived would afterward attribute their survival to the touch of the king’s “healing hands.”

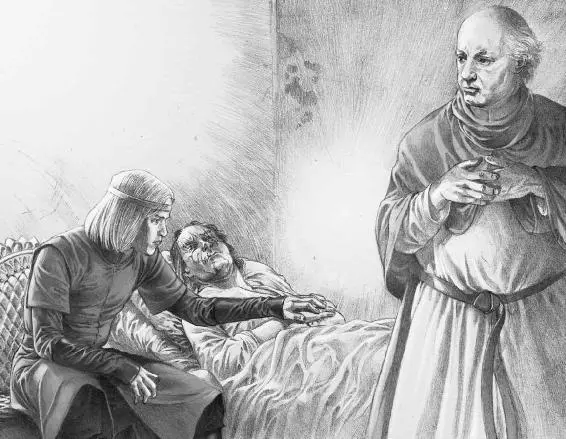

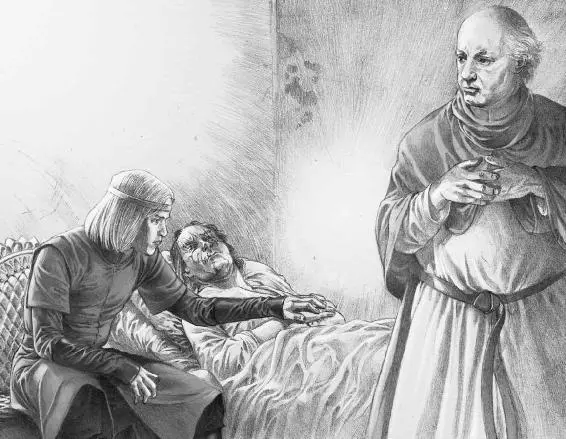

Yet if indeed there is some magic in a king’s touch, as many smallfolk believe, it failed when it was needed most. The last bedside visited by Aegon III was that of Ser Tyland Lannister. Through the city’s darkest days, Ser Tyland had remained in the Tower of the Hand, striving day and night against the Stranger. Though blind and maimed, he suffered no more than exhaustion almost to the last…but as cruel fate would have it, when the worst was past and new cases of the Winter Fever had dropped away to almost nothing, a morning came when Ser Tyland commanded his serving man to close a window. “It is very cold in here,” he said…though the fire in the hearth was blazing, and the window was already closed.

The Hand declined quickly after that. The fever took his life in two days instead of the usual four. Septon Eustace was with him when he died, as was the boy king that he had served. Aegon took his hand as he breathed his last.

Ser Tyland Lannister had never been beloved. After the death of Queen Rhaenyra, he had urged Aegon II to put her son Aegon to death as well, and certain blacks hated him for that. Yet after the death of Aegon II, he had remained to serve Aegon III, and certain greens hated him for that. Coming second from his mother’s womb, a few heartbeats after his twin brother, Jason, had denied him the glory of lordship and the gold of Casterly Rock, leaving him to make his own place in the world. Ser Tyland never married nor fathered children, so there were few to mourn him when he was carried off. The veil he wore to conceal his disfigured face gave rise to the tale that the visage underneath was monstrous and evil. Some called him craven for keeping Westeros out of the Daughters’ War and doing so little to curb the Greyjoys in the west. By moving three-quarters of the Crown’s gold from King’s Landing whilst Aegon II’s master of coin, Tyland Lannister had sown the seeds of Queen Rhaenyra’s downfall, a stroke of cunning that would in the end cost him his eyes, ears, and health, and cost the queen her throne and her very life. Yet it must be said that he served Rhaenyra’s son well and faithfully as Hand.

Under the Regents—War and Peace and Cattle Shows

King Aegon III was still a boy, well shy of his thirteenth nameday, but in the days following the death of Ser Tyland Lannister he displayed a maturity beyond his years. Passing over Ser Marston Waters, second in command of the Kingsguard, His Grace bestowed white cloaks upon Ser Robin Massey and Ser Robert Darklyn and made Massey Lord Commander. With Grand Maester Munkun still down in the city tending to victims of the Winter Fever, His Grace turned to his predecessor, instructing the former Grand Maester Orwyle to summon Lord Thaddeus Rowan to the city. “I would have Lord Rowan as my Hand. Ser Tyland thought well enough of him to offer him my sister’s hand in marriage, so I know he can be trusted.” He wanted Baela back at court as well. “Lord Alyn shall be my admiral, as his grandsire was.” Orwyle, mayhaps hopeful of a royal pardon, hurriedly sent the ravens on their way.

Читать дальше

![Джордж Мартин - Сыны Дракона [лп]](/books/33039/dzhordzh-martin-syny-drakona-lp-thumb.webp)